Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: Vincent’s Rock

Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren had been busy all of July 2nd. The early morning found him on the Federal right flank scouting the terrain for possible attack avenues in the Culp’s Hill sector. With the 3rd Corps’ forward movement, he was called to the left flank to scout the terrain there. It only took an instant for Warren to ascertain the enormity of Sickles blunder. Looking to the south and west from the summit of Little Round Top, the Army of the Potomac’s Chief Topographical Engineer sent staff officers off in all directions in search of help. Lieutenant Randall Mackenzie was sent to Dan Sickles for help. Sickles could offer none. His troops were stretched to the max as is and he needed all the men he had on hand to hold the line.

Captain Chauncey Reese located George G. Meade, who initially issued orders for Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys 3rd Corps division to take up residence on the hill. By the time Humphreys received the order is was too late and the Confederate’s were advancing.

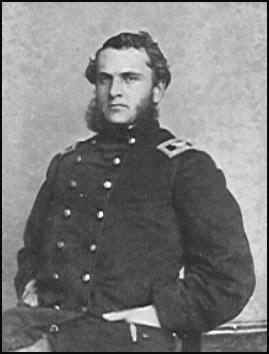

Undaunted by Sickles rebuff, Mackenzie made his to Maj. Gen. George Sykes, the new 5th Corps commander. Sykes men were arriving on the field just north of Little Round Top. Although new to corps command George Sykes was a veteran of the battlefields of First Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. He dispatched a staff officer to locate his closets division, that of Brig, Gen. James Barnes. Barnes was to send troops to the endanger point. Although it is unclear exactly how the unit that was to take the hill was chosen (there are a number of differing accounts), what is clear is that the orders reached 26-year-old Col. Strong Vincent.

Vincent, a native of Erie, Pennsylvania and a Harvard trained lawyer, commanded the 1,335 men of the 3rd Brigade, 5th Corps. “Vincent was of medium stature, but well formed,” recalled one of the colonel’s most ardent admirers Oliver W. Norton. “He was a fine horseman, and when mounted looked much larger than when on foot. He was a gentleman by nature, quiet and considerate in his demeanor, deserving and receiving the respect of his men and officers…” Acting with alacrity, Vincent turned command of the brigade over to Col. James Rice of the 44th New York, with orders to take the brigade to the hill. Vincent rode ahead to scout his newly assigned position.

In the meantime, Warren rode off in search of troops himself. Near the hill, he located another 5th Corps brigade and a battery of artillery. They too were ordered to the hill. Vincent’s men would arrive first.

After scouting the hill, Vincent found that the eastern side was completely deforested, though it was strewn was an inordinate amount of rocks. He was able to see the Confederate’s strike Devil’s Den first and knew that it was only a matter of time before they hit Little Round Top.

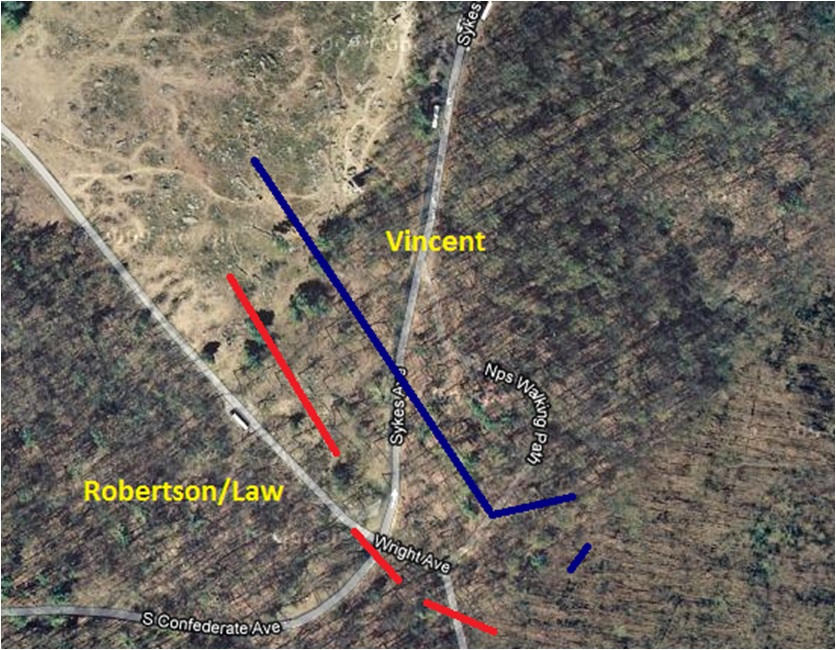

With the eastern side safe from assault, since Sickles men prevented a rebel movement in that direction; Vincent located a small shelf of ground on the south side of the hill, today known as Vincent’s Spur. The former lawyer deployed his brigade roughly a third of the way down the side of the hill at the military crest of the hill. On the left end of the line he placed the 20th Maine, to their right he placed his old regiment, the 83rd Pennsylvania, Vincent continued the line by next placing the 16th Michigan, and the 44th New York on the right of the brigade line. Colonel Rice of the 44th did not like this arrangement. The New Yorkers had a deep bond with their Keystone State counterparts. The two units fought on every battlefield side by side up until this point and were collectively nicknamed the “Potomac Blues.” Rice asked to keep that tradition alive. Vincent consented and ordered the 16th Michigan to take up position on the right flank. “The ground occupied by the brigade…was nearly that of a quarter circle,” wrote Col. Rice after the battle, “composed mostly of high rocks and cliffs on the center, and becoming more wooded and less rugged as you approached to the [brigade] left.”

With the eastern side safe from assault, since Sickles men prevented a rebel movement in that direction; Vincent located a small shelf of ground on the south side of the hill, today known as Vincent’s Spur. The former lawyer deployed his brigade roughly a third of the way down the side of the hill at the military crest of the hill. On the left end of the line he placed the 20th Maine, to their right he placed his old regiment, the 83rd Pennsylvania, Vincent continued the line by next placing the 16th Michigan, and the 44th New York on the right of the brigade line. Colonel Rice of the 44th did not like this arrangement. The New Yorkers had a deep bond with their Keystone State counterparts. The two units fought on every battlefield side by side up until this point and were collectively nicknamed the “Potomac Blues.” Rice asked to keep that tradition alive. Vincent consented and ordered the 16th Michigan to take up position on the right flank. “The ground occupied by the brigade…was nearly that of a quarter circle,” wrote Col. Rice after the battle, “composed mostly of high rocks and cliffs on the center, and becoming more wooded and less rugged as you approached to the [brigade] left.”

The Wolverine’s, Empire Staters, and Pennsylvania’s all shook out companies into skirmish lines. Company A of the 83rd PA was on the line when green-backed sharpshooters of Company F 2nd United States Sharp Shooters fled back to the cover of the rocks on the hill and fell in with the men. More than a dozen men of Company B, 2nd U.S.S.S. fell in with the 20th Maine, who had detached their own Company B on the left flank of the brigade. Other sharpshooters filled the valley below. Sharpshooters making their way to the rear could mean only one thing, the enemy was hot on their heels.

Just as Company B of the 44th New York came on the skirmish line they were hit head-on with a volley.

The first Confederates to strike the Federal line on Little Round Top were the 4th Alabama. The Alabamians linked up with 4th and 5th Texas, and the three units, from two different brigades, pressed hard for Vincent’s men. “….Scarcely had the troops been put in line when a loud, fierce, distant yell was heard, as if all pandemonium had broken loose and joined in the chorus of one grand universal war-whoop.”

The Federal skirmish line melted like snow in direct sunlight. The rebels thrust forward with a fury. “We advanced up the mountain under a galling fire,” wrote Lt. Col. L.H. Scruggs of the 4th Alabama, “driving the enemy before us until we arrived at a second line, where a strong force was posted…”

A close-range firefight took place along Vincent’s Spur. “In an instant a sheet of smoke and flame burst from our whole line, which made the enemy reel and stagger.” The Confederates countered “firing with accuracy and deadly effect.”

Vincent became nervous about the prospect of holding the hill. Turning to his adjutant, the young colonel said “Go….and tell Gen. Barnes to send me reinforcements at once: the enemy are coming against us with an overwhelming force.”

The center of the Federal line held firm, so the rebels looked for the flanks of the brigade. Locating the right flank, the southerners made a renewed effort to dislodge the Yankees. “The regiments were again ordered forward, which they did in the most gallant manner,” remembered a member of the 5th Texas.

Pvt. W. J. Barbee of Company L, 5th Texas “mounted a rock upon the highest pinnacle of the hill, and there, exposed to a raking, deadly fire from artillery and musketry, stood until he had fired twenty-five shots, when he received a Minie ball wound in the right thigh, and fell.”

Confusion reigned supreme everywhere. Nearly all our field officers were gone. Hood, our major general, had been shot from his horse. Robertson, our brigadier, had been carried from the field [wounded in the leg]. Colonel [Robert M.] Powell of the Fifth Texas was riddled with bullets. Colonel Van Manning of the Third Arkansas was disabled and [Lt.] Colonel [Benjamin] Carter of my regiment [the 4th Texas] lay dying at the foot of the mountain.

The 16th Michigan came under intense pressure. The Confederate line was no longer a true line. Butternut soldiers fought in groups behind the large boulders. “From some misconstruction of orders,” someone, allegedly the Lt. Col. of the regiment ordered the colors of the 16th Michigan to fall back. Seeing their flags move to the rear, so too did half of the regiment.

The 16th Michigan came under intense pressure. The Confederate line was no longer a true line. Butternut soldiers fought in groups behind the large boulders. “From some misconstruction of orders,” someone, allegedly the Lt. Col. of the regiment ordered the colors of the 16th Michigan to fall back. Seeing their flags move to the rear, so too did half of the regiment.

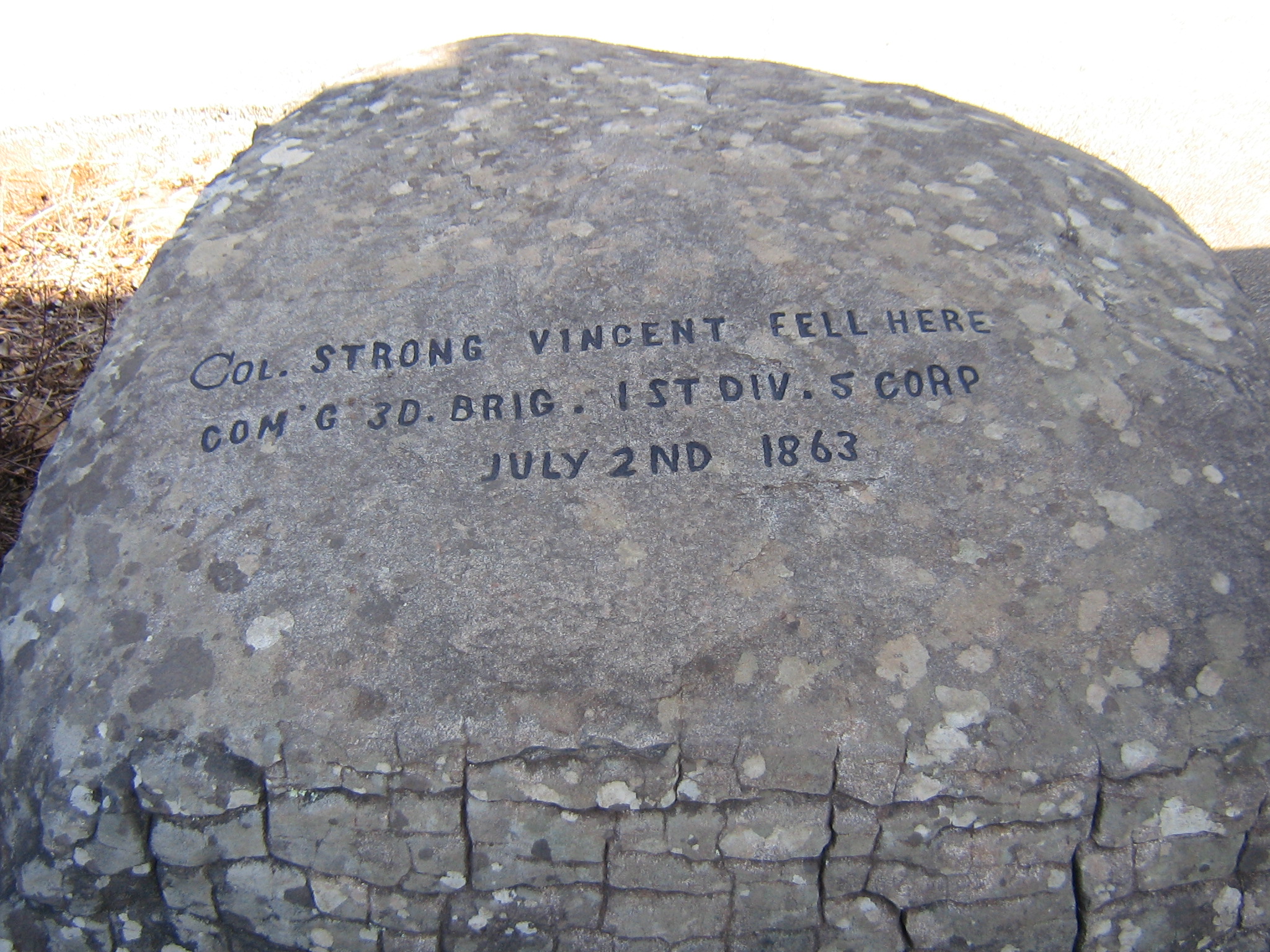

The moment of crisis on the brigade right had reached a boiling point. Leaping atop a rock to help steady his troops, riding crop in hand, Vincent bellowed out “Don’t give an inch!” Moments later Vincent was felled by a Confederate bullet, mortally wounded in the left thigh. He was carried to the Lewis Bushman Farm where he died five days later. The day before his wounding Vincent was quoted as saying “What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania fighting for that flag?”

As the story goes, on July 7th, while on his deathbed, Vincent’s promotion to brigadier general arrived.

Two months later Vincent’s wife gave birth to a daughter.

Authors Note:

There are essentially three monuments to Vincent on Little Round Top, the inscribed rock. Another headstone like monument on lower Vincent’s Spur. A third and final one is atop the 83rd Pennsylvania’s monument. An officer with a striking resemblance to Vincent stands atop said monument. While, another monument stands in his home town of Erie, Pennsylvania.

The rock in this post was inscribed anywhere between the summer of 1864 and 1865. One account places the inscription on the rock as of October of 1864. Another mentions the inscription in the summer of 1865. Who actually inscribed the rock is unknown to us.

If Vincent did indeed fall on this spot, he fell within 100 yards of some other Union heroes who died in the defense of Little Round Top:

Brigadier General Stephen Weed, who was the former 5th Corps artillery chief and led a mixed Pennsylvania & New York brigade to the top of the hill and secured Vincent’s right flank.

Lieutenant Charles Hazlett brought Battery D, 5th United States Artillery to the top of the hill. From there, his six 10-Pounder Parrot Rifles supported the Federal line.

Then there was Colonel Patrick O’Rorke. Paddy graduated at the top of his West Point class in June of 1861. O’Rorke was killed while leading a charge down the southeastern face of Little Round Top.

The actions of Vincent, Weed, Hazlett, and O’Rorke have all been overshadowed by one man, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. Chamberlain’s fame has grown exponentially since the battle. His postwar self-aggrandizement, coupled with the release of both The Killer Angels, and the movie Gettysburg, have tainted the historiography of the battle forever. (See Garry Adelman’s excellent book The Myth of Little Round Top; or Thomas Desjardin’s These Honored Dead: The Story of How Gettysburg Shaped American Memory.) If it’s any consolation to O’Rorke, he does have a pretty bitchen bar in town named after him. We at ECW highly recommend it!

To Reach Vincent’s Rock:

-From the town square, follow Baltimore Street south for 0.5 miles.

-At the Y intersection bear to the right and follow Steinwehr Ave. for 0.2 miles.

-At the traffic light, turn left onto the Taneytown Road.

-Follow the Taneytown Road for 2.6 miles and then turn right onto Wright Ave. (If you cross over the top of the 15 bypass you have gone too far).

-Follow Wright Ave. for 0.6 miles (don’t miss the Vermont Brigade Monument along the way, it’s pretty cool).

-At the intersection turn right and ascend Little Round Top. Park where you can find a spot.

-Exit your car and go to the 12th & 44th New York Monument atop the hill, it’s the big castle. If you can’t find this monument get in your car and go home, you will never find the rock.

-Stand facing the front of the castle. A small cluster of boulders is to the left, with a path way leading between the boulders and monument. The engraved rock is among those boulders.

PLEASE USE EXTREME CAUTION CLIMBING ON THE ROCKS.

Awesome stuff. Thanks.

Wow Gary Adelman must be a jaded Pennsylvanian to have written that book. How does he know what happened? Chamberlain was there, Adelman was not.

Well, Garry is from Chicago and not Pennsylvania, and he is one of the leading historians on the subject. Chamberlain was well known to embellish his war time stories. His former second in command loathed him and his embellishments (we have the letters). Chamberlain is trained in rhetoric (that is a fact). The story that he tells about Little Round Top changes from audience-to-audience, account-to-account, year-to-year (all of these exist and you can read for yourself). The commander of the brigade and all three of the other regimental commanders of the 83rd PA, 16th MI, and the 44th NY did not survive the war to tell their stories (another verifiable fact). Chamberlain even disagreed with his own soldiers as to what they did and where the 20th Maine’s monument should be placed (feel free to see those sources, too). In short, Garry and many others have done the research to find out what happened on the hill, and did not just take one persons varying accounts at face value.

This is the kind of material we all love . Thanks!!

When I visited on Halloween of 2024, my own observations lead me to believe that the inscribed rock is indeed the most probable location that Vincent was shot. He was then taken behind the rock with the marble marker (which is facing the opposite direction of the original) to be treated. I believe one of the 2 biographies or Norton’s book states that Vincent remained there until the LRT battle was over on July 2, 1863. I think the confusion is simply some witnesses saw Vincent behind the rock with the marble marker and incorrectly assumed that was the location he was shot. From the accounts I have read Vincent was running up and down his line encouraging the men and the rock with the marble marker may have been in the area of his main observation or command location.