The Great March From Cumberland Gap

Today in 1862 ended one of the epic marches in American military history, the evacuation of the Union garrison at Cumberland Gap to the Ohio River. The men, 7,000 under Brigadier General George W. Morgan, endured a test not often found in the annals of the United States Army. What they achieved is on a par with other great movements like Benedict Arnold’s march to Quebec in 1775, Stephen Kearny’s march to California in 1846, and Joseph Stilwell’s walkout from Burma in 1942. Yet it is largely forgotten outside of Kentucky.

Today in 1862 ended one of the epic marches in American military history, the evacuation of the Union garrison at Cumberland Gap to the Ohio River. The men, 7,000 under Brigadier General George W. Morgan, endured a test not often found in the annals of the United States Army. What they achieved is on a par with other great movements like Benedict Arnold’s march to Quebec in 1775, Stephen Kearny’s march to California in 1846, and Joseph Stilwell’s walkout from Burma in 1942. Yet it is largely forgotten outside of Kentucky.

Here is that story.

When the Confederates invaded Kentucky in August 1862, a 9,000-strong division under Carter Stevenson diverted to besiege George Morgan’s garrison at Cumberland Gap. Cut off from the outside, the men (many from East Tennessee and Eastern Kentucky) could only watch their rations diminish and wonder at what was happening elsewhere. No word came as August turned into September.

On September 6 the garrison’s bread ran out. Six days later, later the post quartermaster reported that feed for the horses and mules was almost exhausted. If these animals starved to death, the garrison would lose its mobility and would never be able to leave the Gap.

George Morgan now faced a critical decision. On September 14 he met with his staff and senior commanders. After considering the situation carefully, all present agreed that the Gap needed to be evacuated. Having thus decided to leave Cumberland Gap, the next question was where to go. A march on the Old Wilderness Road toward Lexington or Central Kentucky would mean a likely encounter with Confederates, not something George Morgan was willing to risk with his half-starved men. Win or lose, his force might be so crippled by a major fight that it would be unable to get to Union lines.

The only other alternative was to go through the mountains to the Ohio River, 200 miles to the north. But this option meant a major movement into a wild region using narrow roads and defiles that could easily be blocked by an intrepid opponent. George Morgan marked a possible route on a map, and he showed it to some officers who were familiar with Eastern Kentucky’s mountains. Almost to a man they agreed it would be a tough road, with little forage or water to be found. One officer, the former Kentucky State Geologist, said that the Federals could “possibly” get through, but only “by abandoning the artillery and wagons.” Despite the risks, George Morgan decided to try and bring out his whole force through the mountains.

After several days of preparations, George Morgan’s men left Cumberland Gap at 8 P.M. on September 17. They burned everything not movable and blocked the road to delay pursuit. Turning northeast past Manchester, the Federals moved into the mountains while Confederates under John Hunt Morgan and Humphrey Marshall exerted every effort to block their progress, While the wagons moved through defiles, East Tennessee infantry covered from the ridges above.

George Morgan later summarized the hunt in the Eastern Kentucky mountains: “Frequent skirmishes took place, and it several times happened that while the one Morgan was clearing out the obstructions at the entrance to a defile, the other Morgan was blocking the exit from the same defile with enormous rocks and felled trees. In the work of clearing away these obstructions, one thousand men, wielding axes, saws, picks, spades, and block and tackle, under the general direction of Captain William F. Patterson, commanding his company of engineer-mechanics, and of Captain Sidney S. Lyon, labored with skill and courage. In one instance they were forced to cut a new road through the forest for a distance of four miles in order to turn a blockade of one mile.” The Confederates finally broke off pursuit October 1.

On October 3, 1862, George Morgan’s command crossed the Ohio River at Greenupsburg. After 219 miles and 16 days on the road, they had made it despite limited water, dwindling rations, and Confederate efforts. Federal losses totaled 80 men killed, wounded, and missing/deserted. Despite all odds, George Morgan had brought his men, wagons, and artillery to safety in the Buckeye State.

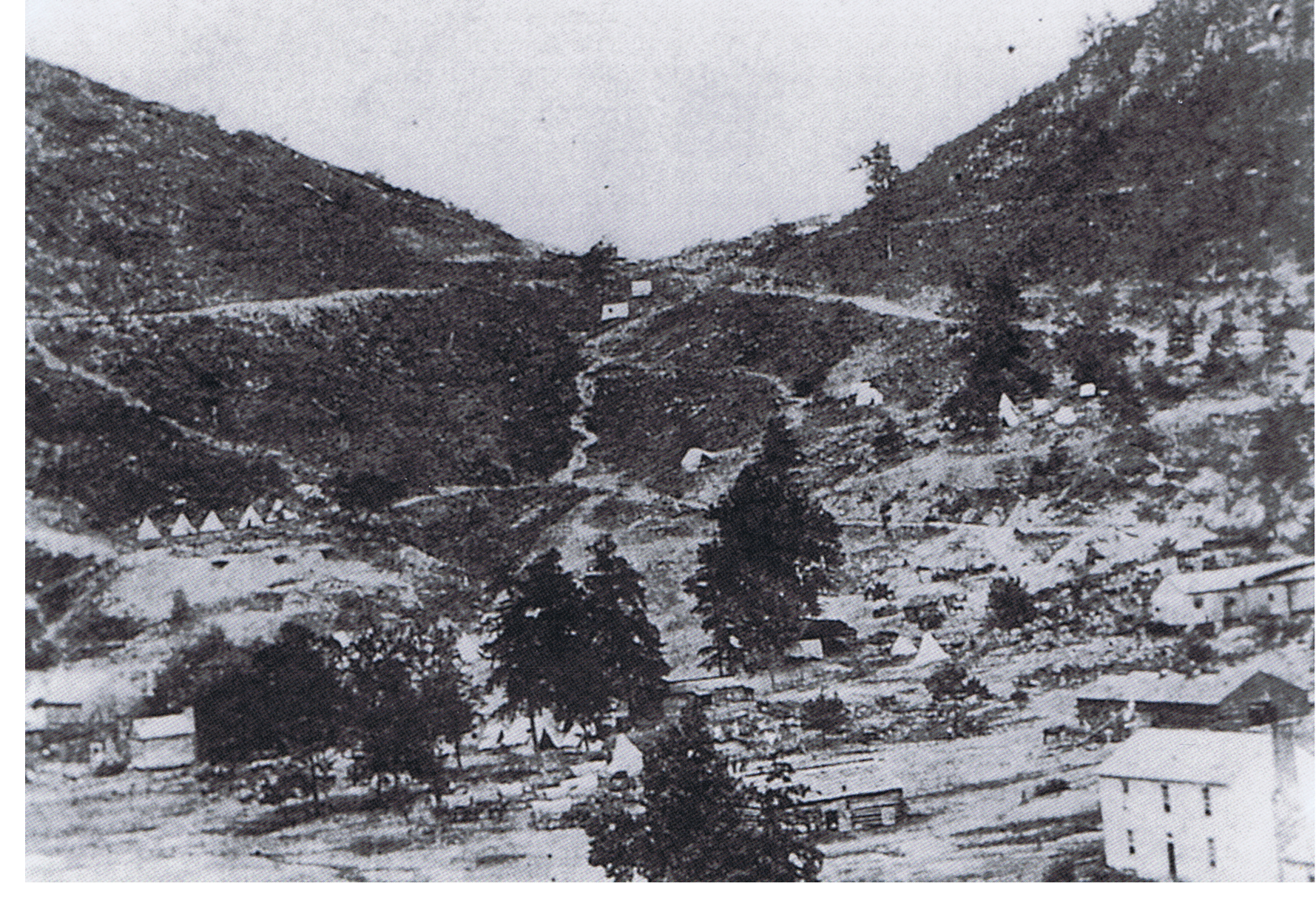

Top: Cumberland Gap during the Civil War.

Bottom: George W. Morgan.

The campaigns in and around the Gap, while always peripheral, were significant. A year later, a Confederate Brigade would become trapped in the Gap and be forced to surrender, which caused an uproar in Richmond.