1860’s Politics: After All These Years, Why Do We Think President McClellan Would Have Given the Rebels an Armistice?

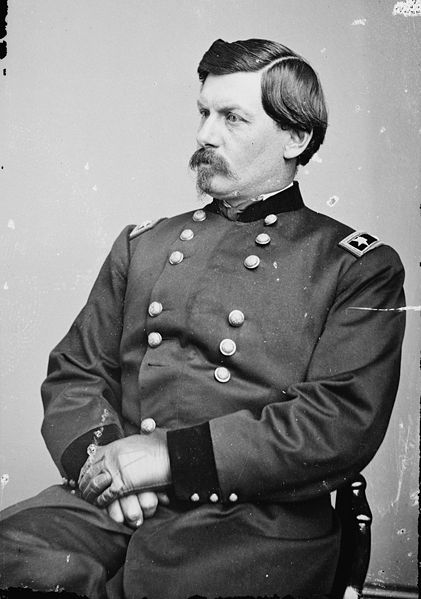

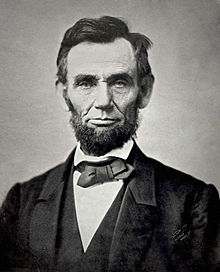

Approaching the 1864 Northern presidential election, students of the Atlanta Campaign tend to focus on how Sherman’s capture of the city on Sept. 2, 1864 helped President Lincoln win re-election. Conversely, we ponder Southerners’ hopes that the Democratic candidate, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, might have beaten Lincoln if the Confederate Army of Tennessee had been able to hold the city till the election of November 8. Once in office, President McClellan might have abided by his party’s platform plank calling for an armistice to end the war. And maybe, once the fighting stopped, the North might have acceded to the Southern states’ secession, in effect granting the Confederacy its independence.

Approaching the 1864 Northern presidential election, students of the Atlanta Campaign tend to focus on how Sherman’s capture of the city on Sept. 2, 1864 helped President Lincoln win re-election. Conversely, we ponder Southerners’ hopes that the Democratic candidate, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, might have beaten Lincoln if the Confederate Army of Tennessee had been able to hold the city till the election of November 8. Once in office, President McClellan might have abided by his party’s platform plank calling for an armistice to end the war. And maybe, once the fighting stopped, the North might have acceded to the Southern states’ secession, in effect granting the Confederacy its independence.

The idea has been around for a long time—actually, from the very war years. The late Albert Castel gave it renewed currency in his Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864 (1992). As for a possible Confederate victory in late August ’64, Castel asserts, “all that the South needed to do to achieve it is to hold fast a while longer—just six more weeks—until the Northern elections get under way” (p. 480).

A few years later Dr. Castel reinforced his argument in an essay entitled “The Atlanta Campaign and the Presidential Election of 1864: How the South Almost Won by Not Losing.” While he acknowledged “there is, of course, no way of knowing…what would have occurred had McClellan become president,” Castel wrote that if Confederates had succeeded in holding Sherman out of Atlanta, the event would have weakened the North’s war will, which perhaps could have led to its giving up on the struggle and by default, agreeing Confederate independence. As it happened, “the fall of Atlanta…turned what Republicans and Democrats alike had perceived as certain victory for McClellan in the upcoming presidential election into foregone defeat” (Winning And Losing in the Civil War [1996], 29).

The assumption is clearly that McClellan would have ended the war before Union armies achieved total victory. Richard McMurry repeated the assumption in his Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy (2000): Atlanta’s fall in September 1864 “assured Lincoln’s reelection, and in so doing it assured the eventual failure of the Southern bid for independence” (p. 190). In other words, Atlanta 1864 was indeed “the last chance for the Confederacy.”

Writing for the ECW blog series “1860s Politics” invites one to consult the authorities, especially when dealing with long-held assumptions (here, that McClellan’s election in effect equaled Southern independence).

So I turned to James G. Randall’s venerable The Civil War and Reconstruction to double-check what I had read in the recent literature. I found no corroboration at all, but a refutation. In 1937—1937, mind you!—Professor Randall, in his now-classic history, was already reacting to a “stereotyped picture,” “the familiar tradition regarding the election of 1864.” That stereotype, Randall explained, held that while Lincoln campaigned for a continued waging of the war, McClellan’s candidacy was staked to armistice and peace. The “familiar tradition” posited that “Democratic victory would have brought defeat in the war and failure to the Union cause,” Randall asserted.

In other words, three generations ago Castel’s and McMurry’s interpretation of the 1864 election had become so commonplace that a revision was in order. Randall thus proceeded to pick apart the “stereotyped picture.” 1) Both Lincoln’s Union/Republican Party and McClellan’s Democratic Party “favored the restoration of the Union as the chief point at issue.” 2) There was, indeed, a “peace plank” in the Democratic platform of August 1864, but Republican “party propaganda” zeroed in on it in order to tarnish McClellan and impute “treasonable motives” to his supporters. 3) Besides the “war Democrats” (led by McClellan), there were Northern “peace Democrats,” led by former Ohio congressman Clement Vallandigham (derisively dubbed “Copperheads”). But even they “declared for peace on the basis of reunion,” Randall pointed out, meaning an end of the war based on restoration of the Union. As we know, this was a condition which Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government would have rejected out of hand–as it did in the Hampton Roads conference of February 1865 (J.G. Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction [1937], 622-24).

Has Randall’s work been updated? Notably, yes, by David H. Donald and reissued in 1961. Randall and Donald’s The Civil War and Reconstruction was hailed by Nevins, Robertson and Wiley in their Civil War Books (1967) as “one of the most fundamental sources for any study of the war.” Professor Donald updated parts of Randall’s text, “bringing it in line with centennial-era scholarship,” as David Eicher puts it (The Civil War in Books [1997], p. 264).

For this essay I compared Randall’s treatment of the 1864 election with Donald’s updating, and found that Randall’s repudiation of the familiar stereotype still stood. Professor Donald, though, added an amplifying paragraph whose main point was that the differences between candidates Lincoln and McClellan “were more a matter of shading than of glaring contrast.” Most of McClellan’s supporters were “unquestionably loyal citizens who favored the vigorous prosecution of the war.” Yet the Democrat was also supported by a “small but noisy anti-war faction” whose outsized roar worried even Lincoln into thinking he might not win re-election. Among Republicans, Donald characterizes most as “undoubtedly moderates who desired nothing more than the restoration of peace and the Union.” Lincoln had his own loud minority, the Radical wing of his party.

Randall/Donald’s conclusion was that as stated in 1937: if the Democrats had won the presidency, McClellan would have set policy, not Vallandigham. And McClellan would have understood his triumph as a popular mandate “to prosecute the war as a conflict whose object was restoration of the Union” (Randall and Donald, 1961 ed., pp. 478-79).

So the question is, how could a scholarly interpretation of the Northern presidential election of 1864 which saw the differences between Lincoln and McClellan merely as “shading” be supplanted, a generation later (Castel) and a decade after that (McMurry), by one which viewed the two candidates as diametrically opposite on the matter of continued prosecution of the war?

Randall and Donald rightly pointed to both the noise created by the Vallandigham crowd and the indignant backlash of the Republican campaign machine as sources of McClellan’s wartime portrayal as a peacenik. Another reason for the alleged Lincoln-McClellan platform dichotomy has to do with what Confederate Southerners were writing in 1864.

That subject will await my next post for the ECW “1860’s Politics” blog series.

Excellent points, which bring up some other interesting questions: Why then was Lincoln so concerned that he would write his famous secret note? What kind of Commander-in-Chief would McClellan have been? Would he have given Grant and Co. free reign to do wheat needed to be done, what was done? Thanks for the great discussion.

Stephen:

As I recall, McClellan publicly stated he would continue prosecuting the war, if elected. However, he made this statement only AFTER Sherman captured Atlanta. By that time, of course, Lincoln’s chances for re-election had greatly improved. His chances for re-election were enhanced even more when Sheridan later vanquished Jubal Early in the Valley campaign.

Am I correct in my recollection about the timing of McClellan’s continuing-the-war statement?

Side note: While Castel’s argument about whether McClellan would have continued the war can be debated, the excellence of Decision in the West cannot be questioned, as far as I’m concerned. It’s one of the best campaign histories I’ve ever read. His critiques of the performances of the generals involved in the campaign is incredibly insightful. He pulls no punches in criticizing almost all of them (except George Thomas).

On June 15, 1864 (well before the fall of Atlanta), McClellan dedicated the Battle Monument at West Point where he called the rebellion “gratuitous and unjustifiable.” He then continued:

“To efface the insult offered our flag; to save ourselves from the fate of the divided republics of Italy and South America, to preserve our government from destruction, to enforce its just power and laws, to maintain our very existence as a nation – these were the causes that compelled us to draw the sword.

“Rebellion against a government like ours, which contains the means of self-adjustment, and a pacific remedy for evils, should never be confounded with a revolution against despotic power, which refuses redress of wrong. Such a rebellion cannot be justified upon ethical grounds, and the only alternative for our choice is its suppression, or the destruction of our nationality. At such a time as this, and in such a struggle, political partisanship should be merged in a true and brave patriotism, which thinks only of the good of the whole country.

“It was in this cause, and with these motives, that so many of our comrades gave their lives, and to this we arc all personally pledged in all honor and fidelity. Shall such a devotion as that of our dead comrades be of no avail? Shall it be said in after ages that we lacked the vigor to complete the work thus begun? That, after all these noble lives freely given, we hesitated, and failed to keep straight on until our land was saved? Forbid it, Heaven, and give us firmer, truer hearts than that!”

Great post, Steve, and great points!

Thank you Kevin for a good after post and helping us better under stand this issue . Seem the yanks were to” fight it out if it takes all summer” !

Thanks, Tom. That’s a great way to say it. Perhaps Grant spoke more than he knew.

Kevin:

Thanks for the clarification. My recollection was obviously incorrect. By the way, I just finished William C. Davis’ The Cause Lost, where he strongly and persuasively argued that a McClellan presidential victory would not have changed anything as afar as prosecution of the war.

Hi Bob,

No worries at all. I think this is one of the great myths of the war (though there are obviously some much larger) and kudos to Steve for bringing it to light here. It does make sense that despite all of the bloodshed and expense in prosecuting the war, Northerners still wouldn’t want to drop the issue and sue for peace. When you’ve invested that much time and effort into something, you never want to come out on the losing side.

To be a bit of a contrarian here, Kevin:

What are the odds a McClellan administration keeps up with Lincoln’s anti-slavery platforms. What are the odds McClellan supports a 13th Amendment, or continuing the practices put into place by the Emancipation Proclamation. If he doesn’t support those steps forward taken by Lincoln, then the major cause of the war is left alone? Let’s say McClellan works out a peace that the southern states surrender and come back into the fold, but with slavery in tact. What’s changed? How long before the country goes back to war?

Ryan:

Interesting question. The answer is complicated (and, of course, can’t be determined with any certainty.) But here’s my attempt:

It’s true that many – if not most – Northern Democrats, including McClellan, opposed the Emancipation Proclamation. But by the end of the war, most Northerners, including Democrats, came to understand that slavery was the No. 1 reason for secession. To ensure this bitter issue never surfaced again, thus leading to another secession, slavery must be abolished, even most Northern Democrats realized by 1865.

In addition, a president McClellan could not have negotiated a peace treaty with the South that included rejoining the Union. The reason: Jefferson Davis would have opposed it, as he did up until the day he was captured.

Davis wanted one thing most of all, independence for the Confederacy. He could probably have negotiated an armistice six months before Lee’s surrender and gotten pretty good terms (not to mention saving thousands of lives). However, Lincoln insisted on two things – re-Union and slavery’s abolition. Davis wouldn’t agree to either, especially the re-Union part.

That said, President McClellan would have been ridiculously generous with South, once it surrendered. He would have made President Andrew Johnson’s slap-on-the-wrist policies look draconian. The odious Black Codes, initiated in the South under Johnson as another form of slavery, would have remained in place. Those Black Codes made Jim Crow look liberal.

ISTR coming across a PhD dissertation that looked at the CSA / Davis’ attempts to influence the 64 election outcomes, via funneling money to confederate agents in Canada for use in campaign actions. The author’s conclusions seemed to be the effort was ineffective in particular because various confederate state governors had their own philosophy on state’s rights and preferred to act via state-to-state action vice a common CSA action. This difference in strategic goals and means resulted in poor execution often at cross-purposes.

In general I think there was a block of conservative Whigs who were unwilling to accept the politics of the “black” Republicans and drifted into the Democrat party as the better home for conservatism.