Shenandoah Valley Campaigns and The Importance of Luck

Part One

With the month of October behind us, I think back on the topic of my first co-publication, Bloody Autumn, the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. To add impetus to the recollections this year, I am currently fine-tuning a presentation that I will be giving to a round table next spring. When reading through my research notes and re-reading some of the great accounts of Shenandoah Valley war histories, I keep coming across one thought: was Jubal Early as a good a general, but maybe not as “lucky” a general in the Valley of Virginia as his predecessor in that district was? Before you flood my inbox with vitriolic filled messages questioning my sanity, let’s take a moment to look at a few specifics.

In the spring of 1862, Confederate General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson mounted an offensive against Union forces under the command of Brigadier General James Shields in the vicinity of Kernstown, Virginia, south of Winchester in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Through some limited reconnaissance by Confederate cavalry and a quick reconnaissance of the terrain, Jackson attacked what he thought was an outnumbered enemy contingent. Instead, he was attacking an entire Union division, numbering close, to 9,000 Union soldiers. Jackson had at his disposal less than 4,000 men. Not the best of odds.

During the battle Jackson shifted regiments, sometimes without consulting the brigade commanders that these units belonged to, to carry the offensive or solidify the existing Confederate line. Although Kernstown would be marked as a defeat for “Stonewall” and recriminations and allegations which led to a court-martial proceeding of his ranking subordinate, Jackson’s star would continue to ascend after that March, 1862 engagement.

The Union forces are content to stay on the defensive, to counteract what Jackson dictates, and then are content to let the Confederates retreat. The Union commander on the field Colonel Nathan Kimball ignores directives from Shields to attack and instead continues to buttress his lines for defense.

Fast-forward two and a half years to the fall of 1864 and Confederate forces again find themselves on the outskirts of Winchester, Virginia. Yet, this time, they are on the defensive to the north and east of the vital crossroads town.

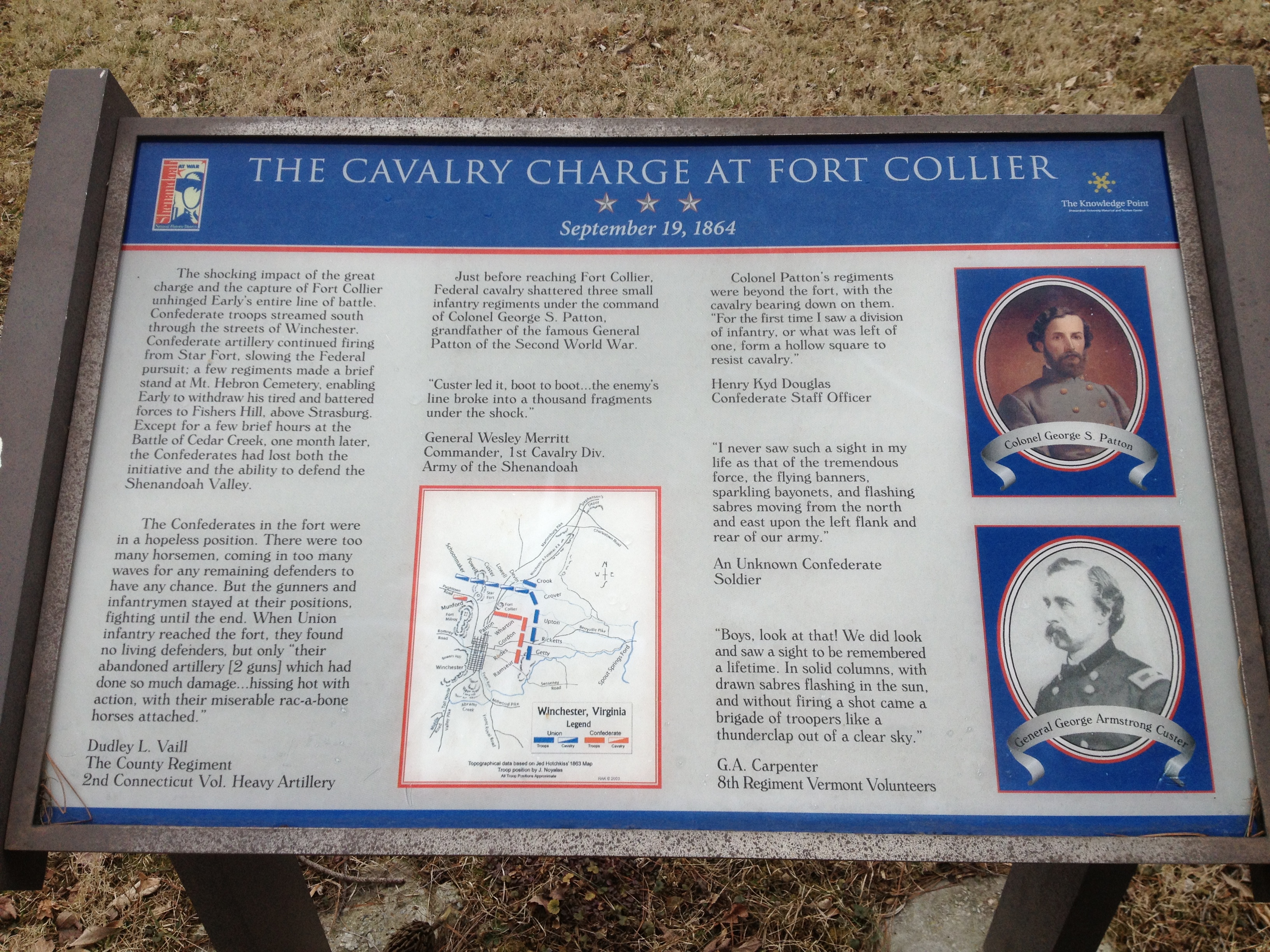

Jubal Early, the Confederate commander, does a superb job of deflecting Union Major General Philip Sheridan’s throughout the morning and early afternoon of September 19, 1864. In a daring move, dare we say, “Jacksonesque” Early pulls the majority of Major General John C. Breckenridge’s Division from north of the town to add weight to his defense to the west, where the primary fighting has been raging all day.

A smart, sound move, still a gamble, as only one infantry brigade, under Colonel George Patton is left, along with Confederate cavalry, to guard that portion of the field. Yet, it is a necessary risk. Early understands he is outnumbered, he understands he has been holding his own against what can be considered piecemeal attacks by Sheridan. But, he senses victory and makes the gamble, hoping for battlefield luck. Maybe even capture some of that Jackson spirit, animate his dependable Second Corps contingent, and steal a victory.

However, Early, is not lucky. Instead, Union cavalry, finding the terrain to the north of Winchester excellent for a mounted charge, will unleash their mounted fury on the outgunned and outnumbered Confederates. The Union timing is impeccable, as Brigadier General Alfred Torbert, under repeated missives from Sheridan, finally organizes the attack.

Early’s left flank disintegrates. The line to the west of the town, comprising almost all of Early’s infantry is flanked and retreats. The day is lost. Winchester is lost. Jackson gambled in 1862, Early gambled in 1864. Jackson faced Kimball and a wounded Shields. Early faced Sheridan. One could afford to lose a risky endeavor. One could not.

Both did exactly what their personality and military acumen dictated. Extenuating circumstances and the need to be perfect in every decision is the difference between Early and Jackson in these two engagements. One could afford to make a mistake as the caliber of the opponent was not up to excellence. The other could not.

Phil:

Interesting post. As you write in the end of your article, a major different between Early and Jackson was that “Early faced Sheridan.” Unfortunately for Old Jube, Little Phil was one of the Union’s most talented and aggressive commanders.

Enjoyable reading ; as Napoleon said about a general:” Is he lucky?”

This would not be the last time Early’s left flank collapses when facing Sheridan’s army.