Alexander Gardner and the Good Death

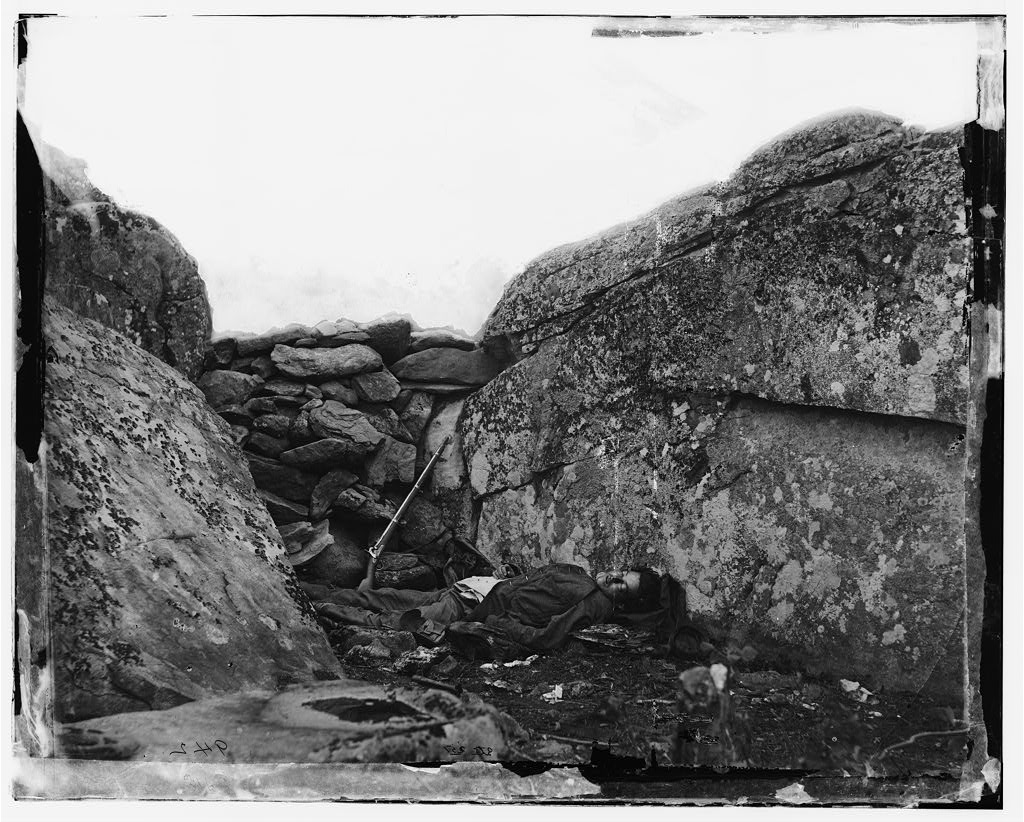

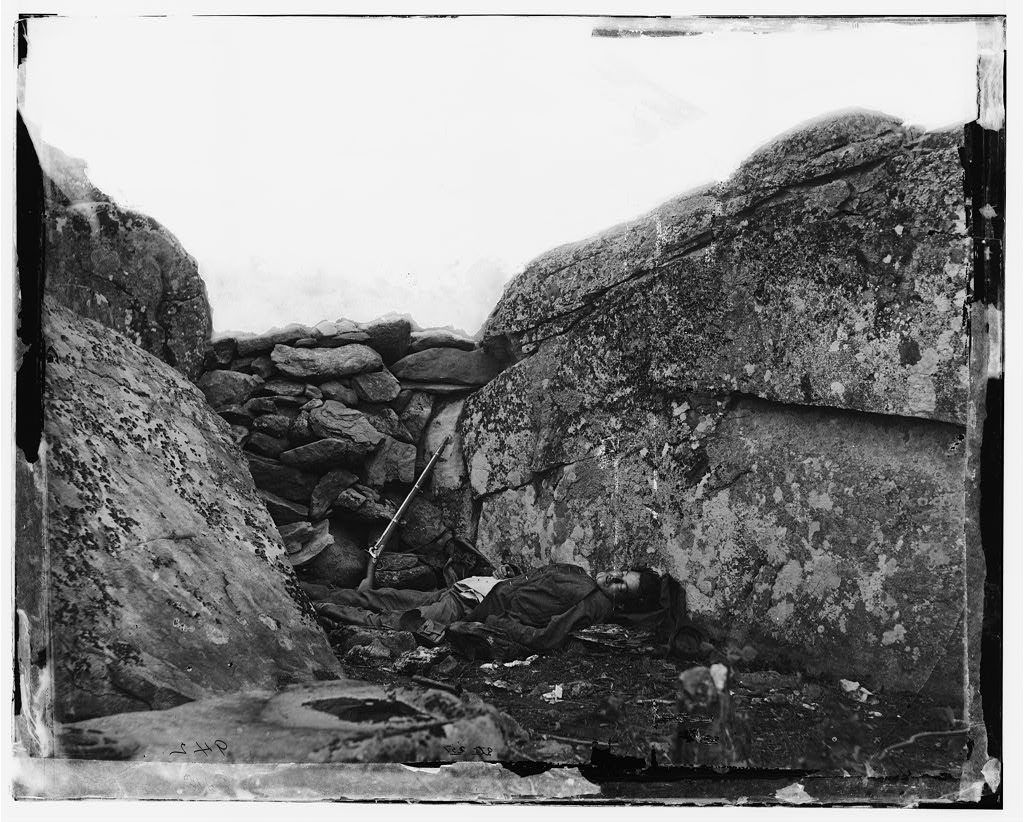

Of the thousands of Civil War photographs, only several truly iconic images exist that specialists and non-specialists alike immediately recognize. One such image is the subject of today’s post: Timothy O’Sullivan’s “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg.” The scene is compelling. A young man, eyes closed, hair disheveled, and mouth ajar lays prone. One arm has fallen to his side while the other rests on his stomach. His body is not yet disfigured or decomposed. He would look asleep were it not for the disturbed clothing, which was torn open while he desperately searched for the fatal wound. We are led to believe that his rifled musket—a weapon that suggests the soldier was not a sharpshooter—leans against a stone wall wedged between two of the great boulders that composed Devil’s Den. It is a powerfully simple message about the brutal nature of war conveyed through an almost timeless figure. We connect to the scene because it engenders sympathy.

The photograph first appeared in 1866 as part of Alexander Gardner’s Sketchbook of the American Civil War 1861-1865. “A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep” precedes it. Both images were the most successful shots from a six-part series. In 1975, William A. Frassanito, through some brilliant detective work, further immortalized the Devil’s Den sharpshooter by contending that Gardner’s crew had moved the body some forty yards from its original resting place—as seen in “A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep”—to stage the shot. The dead Confederate’s youthful face compelled Gardner and he sought “to achieve a sentimental composition,” writes Frassanito.[i] The crew moved the body by blanket to the stone wall and in “what must have been a flash of creative excitement” improvised the scene.[ii] Richard D. Pougher, a historian of material culture, later challenged Frassanito’s claims insisting that the two images contain different bodies as seen through an analysis of clothing, hair, and facial features.[iii] Most recently, John Heiser of the Gettysburg National Military Park published an excellent three-part series on the image attempting to identify when the man fell and to what unit he was attached.[iv] As these rich discussions demonstrate, over one and fifty hundred years after it was taken, “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg” continues to engender discussion and compel viewers.

Although I’ve seen the Devil’s Den sharpshooter image countless times over the years, I didn’t start really thinking about it until fairly recently when writing on what Nineteenth-Century Americans called the Good Death. The photograph and its 1866 narrative are powerful statements about the cultural shifts enacted by America’s Civil War. In the antebellum era, Catholic and Protestant faiths held deep assumptions about the “proper” way to die. In This Republic of Suffering, historian Drew Gilpin Faust offers a definitive account of the Good Death noting the meaning it assigned to an otherwise cruel, senseless event. In ritual fashion, survivors noted if last words were spoken; highlighted the proximity to kin; and offered moving condolence letters. What happened, though, when a soldier died far from home or if a young man succumbed to disease in a hospital, not on the battlefield? Were these good deaths? “Soldiers and their families struggled in a variety of ways,” Faust writes, “to mitigate such cruel realities, to construct a Good Death even amid chaos, to substitute for missing elements or compensate for unsatisfied expectations.”[v]

The Civil War created problems in how Americans thought about and dealt with death and dying and “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg” conveys these tensions. Elements of the image align perfectly with the Good Death. So much so, one scholar contends, that it “closely resembles a postmortem photograph.”[vi] The young man’s placid expression, his head resting on a knapsack, and no overt signs of violence suggest a peaceful end. Even the staged nature of the scene wouldn’t have surprised Nineteenth-Century Americans because of their familiarity with postmortem photography. But Gardner sought to complicate this portrait and, I’d argue, grapple with the problem of wartime death through his written narrative. He sets the scene by starting with Lee’s retreat on July the fourth and depicting a blasted landscape. Amidst this chaos, “The artist, in passing over the scene of the previous days’ engagements, found in a lonely place the covert of a rebel sharpshooter, and photographed the scene presented here.” Gardner’s focus on the “lonely place” is important because family and friends did not surround the young soldier in his last moments, as had been the antebellum tradition and a necessary part of the Good Death. Instead, Gardner continues, the Confederate suffered intensely and seemingly alone. He pushes the issue further by confronting the man’s final moments in which, ideally, he would have conveyed to an intimate associate his willingness to die and his last wishes. According to Gardner, the Confederate soldier was afforded no such opportunity. The narrator wonders: “Was he delirious with agony, or did death come slowly to his relief, while memories of home grew dearer as the field of carnage faded before him? What visions, of loved ones far away, may have hovered above his stony pillow!”[vii]

Gardner’s words coupled with the image create a dichotomous scene in which the resting youth is juxtaposed with a lonely, painful death. He continues this thread in the caption’s final paragraph. Returning to Gettysburg on November 19, 1863, Gardner claims to have visited the “Sharpshooter’s Home” again. He wrote, “The musket, rusted by many storms, still leaned against the rock, and the skeleton of the soldier lay undisturbed within the mouldering uniform…‘Missing,’ was all that could have been known of him at home, and some mother may yet be patiently watching for the return of her boy.”[viii] Gardner’s “professional indifference,” writes Professor Franny Nudelman, “stands in stark contrast to the boy’s thoughts of home and to the experience of his mother with which Gardner concludes.”[ix]

At least 620,000 Americans died as a result of the Civil War.[x] However profound these numbers, untold suffering followed as Victorians struggled to make sense of the carnage and reconcile the violent deaths of loved ones with the core values to which they still clung. The “fallen had solved the riddle of death,” Drew Gilpin Faust charges, “leaving to survivors the work of understanding and explaining what this great change had meant.”[xi] “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg” offers an eloquent testimony to Faust’s powerful idea. The Confederate soldier had succumbed to his wounds when Gardner’s crew came upon him on the rock-strewn fields near Little Round Top. The scene clearly moved the crew who sought to make him speak once more through an image, they hoped, that would resonate across time. Gardner paradoxically made the Confederate soldier an Everyman dreaming of home in his fleeting moments on earth but also an anonymous causality of war whose fate remained unknown to the people at home. The image is a meditation on the Good Death while the narrative mediates the results of war. “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg” forces us, the viewer, to grapple with the consequences of war and to consider its effects, thereby demonstrating why this image remains iconic. It speaks to us, it troubles us, and it causes us to question.

Sources:

[i] William A. Frassanito, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), 187.

[ii] Frassanito, 191.

[iii] For a distillation of Pougher’s claims see, Thomas A. Desjardin, These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003), 186-7.

[iv] John Heiser, “The Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter” Revisited, Parts 1, 2, and 3, at “The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park,” https://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2014/08/07/the-home-of-a-rebel-sharpshooter-revisited-part-1/ [accessed 8 May 2017].

[v] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 9.

[vi] Franny Nudelman, John Brown’s Body: Slavery, Violence, and the Culture of War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 122.

[vii] Alexander Gardner, Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the American Civil War 1861-1865 (1866; repr., New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2001), 90.

[viii] Gardner, Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the American Civil War 1861-1865, 90.

[ix] Nudelman, John Brown’s Body, 124.

[x] Scholars such as James David Hacker, Gary Gallagher, and James McPherson have debated this figure.

[xi] Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 267.

I think about a Good Death a lot–not only on my work as a historian but on a personal level as well. I guess, as one gets older, the idea of death becomes more present in one’s thoughts. Your article is lovely and very compelling. I often think maybe our Victorian ancestors had some things figured out that we have forgotten. Thank you.

Thank you for the kind words, Meg. Yes, as I also age death becomes more personal and more immediate. It is therefore not surprising, I suppose, that I turn to the subject more and more in my work. I think, too, about the carnival of death during the war…so pervasive and so consuming. It is a central piece of the conflict and something Victorians clearly grappled with constantly.

James, I certainly have read again and again the story of the moved body, however, there is little evidence the body was moved from the field to the sharpshooters position behind the rock. On the other hand there is lots of evidence including the “pant leg impression” in the 3D stereo views that this fellow was first noticed behind the wall and only moved after that point, perhaps to keep others from either drawing or photographing the iconic “wall position”. I am not sure why individuals continue to propagate a position with little to no underlying argument presented in Bill’s book. Have you read those 3 or 4 paragraphs relating to this image? Perhaps your readers might be interested in knowing that there is a writing on this subject which presents a contrary view – i.e. the body was moved from the wall to the field. The reader need only Google the phrase “devil’s den sharpshooter revisited”. They will be pointed toward an eye opening treatise on this subject with plenty of evidence.