We Happy Few…

Here’s a little curtain-raiser for Battle Above  the Clouds.

the Clouds.

In September 1863, United States Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton initiated one of the more remarkable troop movements of the American Civil War. Stanton, alarmed by the recent Union defeat at the battle of Chickamauga, now feared for the loss of the just-captured city of Chattanooga; and with it, the surrender of the Army of the Cumberland. Insisting that the Federals in Chattanooga needed urgent reinforcement, Stanton – over the objections of Henry W. Halleck and other officers – insisted that 20,000 men be detached from the Army of the Potomac in Virginia and rushed to Tennessee.

Stanton got his way. But when ordered to comply, General George Gordon Meade, commander of the Potomac army, did what officers have done since time immemorial: he chose the two infantry corps he least wanted to keep.

The Union XI Corps included a large number of German-Americans, men who were often scorned by their native-born brethren. The XI Corps also bore the brunt of two difficult tactical days: at Chancellorsville and at Gettysburg, where they were outflanked and all but routed in each action. They were soon unfairly tagged as “the flying Dutchmen” of the Union Army. The Union XII Corps, though not as ethnically distinctive as their brethren in the XIth, served in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862, under Nathaniel P. Banks. There they faced Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, to their reputational misfortune.

The Union XI Corps included a large number of German-Americans, men who were often scorned by their native-born brethren. The XI Corps also bore the brunt of two difficult tactical days: at Chancellorsville and at Gettysburg, where they were outflanked and all but routed in each action. They were soon unfairly tagged as “the flying Dutchmen” of the Union Army. The Union XII Corps, though not as ethnically distinctive as their brethren in the XIth, served in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862, under Nathaniel P. Banks. There they faced Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, to their reputational misfortune.

In the view of the rest of the army, neither corps was fully a part of the “real” Army of the Potomac, made up largely (if not entirely) of those troops who served on the Peninsula with George B. McClellan.

And then there was the matter of leadership.

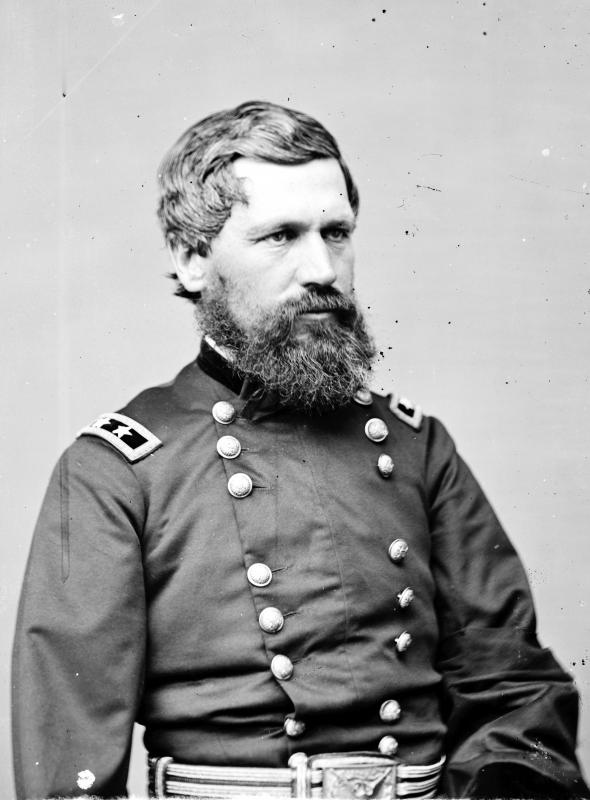

The XI Corps was commanded by Oliver Otis Howard. Howard, a deeply religious, tea-totaling New Englander. Howard replaced Franz Sigel, who was widely popular with the large Germanic element in the XI Corps, but who resigned over matters of rank and seniority. Howard shared some of the prejudices of his fellow native-born Americans, leaving him dubious about his new command. They returned the sentiment. Chancellorsville did nothing to improve the relationship. Howard blamed lower echelon negligence for that disaster, while those same lower echelons remembered that Howard ignored all their warnings.

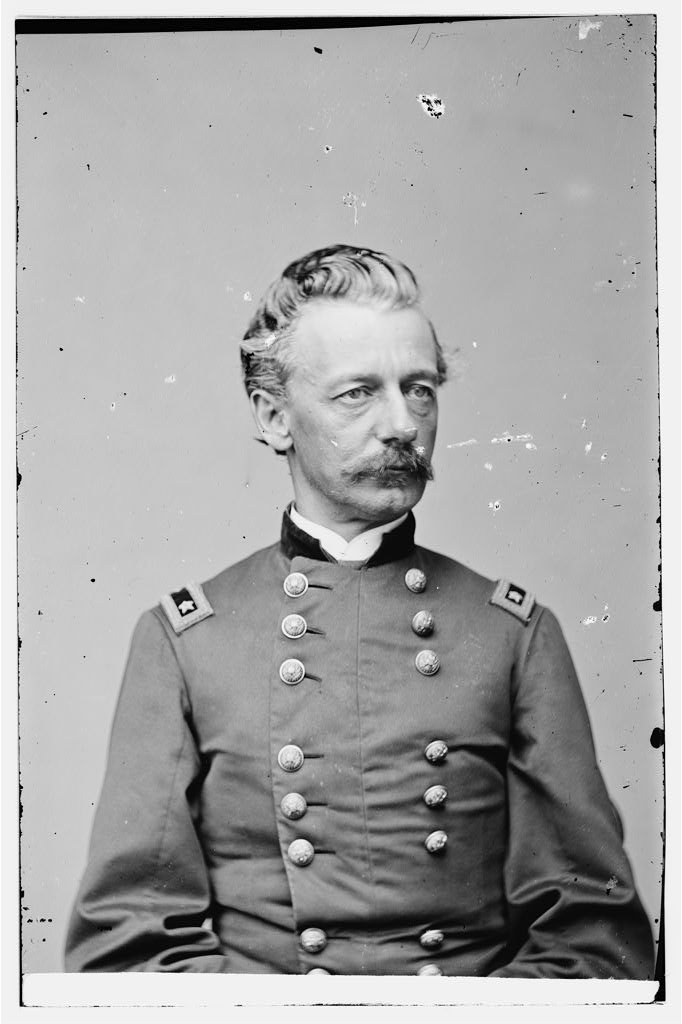

The XII Corps was led by Henry Wager Slocum. While Slocum’s relationship with his corps was better than Howard’s was with the Germans; the relationship between Howard and Slocum was decidedly frosty. Howard assumed command of the field at Gettysburg on July 1 after John F. Reynolds was killed, only to preside over the subsequent collapse of the Union I and XI Corps that afternoon. Slocum’s XII Corps, nearby, was strangely slow in reaching the field. Howard believed that Slocum’s tardiness was deliberate. Slocum purportedly refused to come forward because as the senior officer he would then have to assume command – and the responsibility for what looked a lot like another bad day for the Union. Howard’s brother Charles (a major on the XI Corps staff) reported this information to General Howard. Later, Howard privately wrote that the XII Corps commander fully lived up to his name – slow come – on July 1st.

And to command the expedition? That job was given to Major General Joseph Hooker, the man who recently led the Army of the Potomac at Chancellorsville, and who resigned his position just days before the clash at Gettysburg. And who did Hooker blame for the disaster at Chancellorsville? Howard, of course. Slocum, by contrast, felt that Hooker had stumbled badly in that earlier campaign, and was greatly dismayed to find himself back under “Fighting Joe” Hooker’s command once again.

Thus, Hooker scorned Howard, Howard disliked Hooker and despised Slocum, while Slocum hated Hooker and returned Howard’s disfavor. The troops sent were the Army of the Potomac’s rejects, unwanted and thus the least missed.

This hastily stirred stew of animosities could have portended disaster. In fact, things eventually worked out.

Slocum was the first to leave, wrangling a transfer to Mississippi, thus avoiding service under Hooker at the actions of Wauhatchie, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge. Howard served under Hooker only for the Wauhatchie fight, a small affair that nonetheless managed to produce at least one Union court of inquiry (that of Major General Carl Schurz, whom Hooker accused of negligence: Schurz was cleared of any wrongdoing.) Shortly after Wauhatchie Howard and the XI Corps were loaned out to Major General William T. Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee for the rest of the Chattanooga Campaign. Howard would not serve under Hooker again.

And the men in the ranks? The XI and XII Corps were eventually merged, re-christened as the XX Corps, still under Hooker’s command. Hooker had led them well in the battles for Chattanooga, and both the new corps and their general performed capably during the first half of the Atlanta Campaign.

The former XI Corps men were further relieved when Howard left them entirely, shifting to command the Union IV Corps, comprised of western troops. This meant that while Hooker and Howard served in the same army – The Army of the Cumberland – they both reported directly to Major General George Thomas, who proved equal to the task of managing each man.

But old hatreds die hard. When Major General John B. McPherson was killed at the battle of Atlanta on July 22, 1864, Sherman selected Oliver O. Howard to command the Army of the Tennessee in McPherson’s place. Hooker, who was senior, resigned in protest – which Sherman, who liked Hooker no more than Howard or Slocum, viewed as an added plus.

Slocum then returned from his own self-imposed exile to command the XX Corps in Hooker’s wake. Both Howard and Slocum would accompany Sherman across Georgia and through the Carolinas, each commanding a wing of Sherman’s column.

No band of brothers here…

Excited for the book’s upcoming release, Dave. Early June–just in time for the Civil War Trust’s annual conference, being held this year in Chattanooga!

There’s a good Tennessee Historical Quarterly article from 2006 on the Hooker-Slocum feud, uniquely entitled, Wading in “Deep Water” with a “Driveling Cur”

Thanks, Sam, I have not read that. I will hunt it up.

Another fascinating post by Dave Powell.