Mexican-American War 170th: The Storming of Chapultepec

The American artillery roared. Mortars thumped, arcing shells over the castle’s walls. As a heavy cloud of smoke formed around the muzzles of the cannon and mortars, Winfield Scott kept a close eye on the shelling’s effect. Scott’s target was Chapultepec, an 18th-century castle that, since 1841, acted as Mexico’s military academy. The fortress sat atop a 200-foot high hill, and had a series of brick walls criss-crossing around its perimeter. Chapultepec’s location “commands the city,” in the words of Ethan Allen Hitchcock.[1] There were about 880 Mexican soldiers inside the fortress ready to defend its walls.[2] As a whole, Grasshopper Hill (its translation) presented an imposing obstacle.

After the bloody victory at Molino del Rey, Scott had to decide what to do next. He had two ways into Mexico City: either a southern approach, which would bypass Chapultepec’s brick walls, or the western approach, which ran right through Chapultepec. Scott favored attacking Chapultepec rather than attacking the southern approaches to the city, which Scott characterized as a “network of obstacle[s]” with “unfavorable approaches.”[3] But to hear the thoughts of his subordinates, Scott called for a council of war on the night of September 11.

During the council, Scott put forward his plans to attack Chapultepec and asked for opinions. At first, only division commander David Twiggs supported Scott, with others, including Robert E. Lee, opposed to attacking the fortress. They preferred to march to the south and attack the causeways there, avoiding Chapultepec. Engineer P.G.T. Beauregard then stood up and sided with Scott, proclaiming that he had spent time reconnoitering the southern causeways and found Mexican defenses stronger than they had been at Churubusco. It made more sense, Beauregard argued, to attack Chapultepec. Officers began to change their minds, siding with Scott’s choice, and he stood, announcing, “Gentlemen, we will attack by the western gates. . . the meeting is dissolved.”[4]

Scott’s engineers kept busy on the night of September 11-12 creating the batteries for the artillery. By the morning of the 12th those guns started to bark to life, shelling the fortress in the distance. Ethan A. Hitchcock wrote in his diary, “If we carry Chapultepec, well: if we fail or suffer great loss, there is no telling the consequences.”[5]

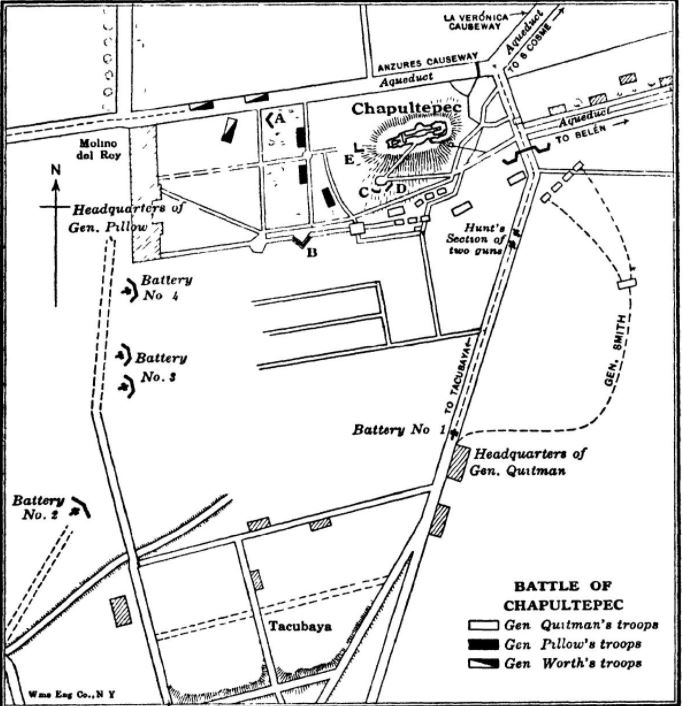

To help the artillery, Scott had Maj. Gen. John Quitman’s division demonstrate near the southern approaches to the city, hoping to trick Santa Anna into thinking they would attack there. The effort paid off, and by nightfall of September 12, Scott moved Quitman’s and Gideon Pillow’s divisions over to join William Worth’s and elements of David Twiggs’s. Scott only left a brigade of infantry near the southern causeway, allocating the majority of his army to the impending attack against Chapultepec.[6]

The attack on September 13 would be made of two prongs. One prong, led by Gideon Pillow’s men, would strike through the captured Molino del Rey. The other prong, made up of David Twiggs, John Quitman, and William Worth’s men, would strike out from near Scott’s headquarters and move to act as a pincer with Pillow. Leading both prongs would be a forlorn hope—a formation of soldiers who would take the brunt of the Mexican fire and clear the way for those after them. As the name implied, there was not much expectation to survive the attack, and requests for volunteers went out. In the words of one historian, “So many volunteered for the mission that lots had to be drawn to determine who would go.”[7] D.H. Hill, who was among the volunteers, explained why so many offered: “To the officers were promised an additional grade by brevet,” and similar incentives of rank and pay offered to the lower ranks.[8] Each forlorn hope ended up consisting of some 250 men, including some 40 Marines commanded by Maj. Levi Twiggs, the general’s brother, who were termed a “storming party”.[9] Second Lieutenant Barnard Bee, who in time would give Thomas J. Jackson an immortal nickname at Manassas, commanded a detachment of regulars in one of the forlorn hopes alongside First Lieut. Israel Richardson, who would fall at Antietam.[10]

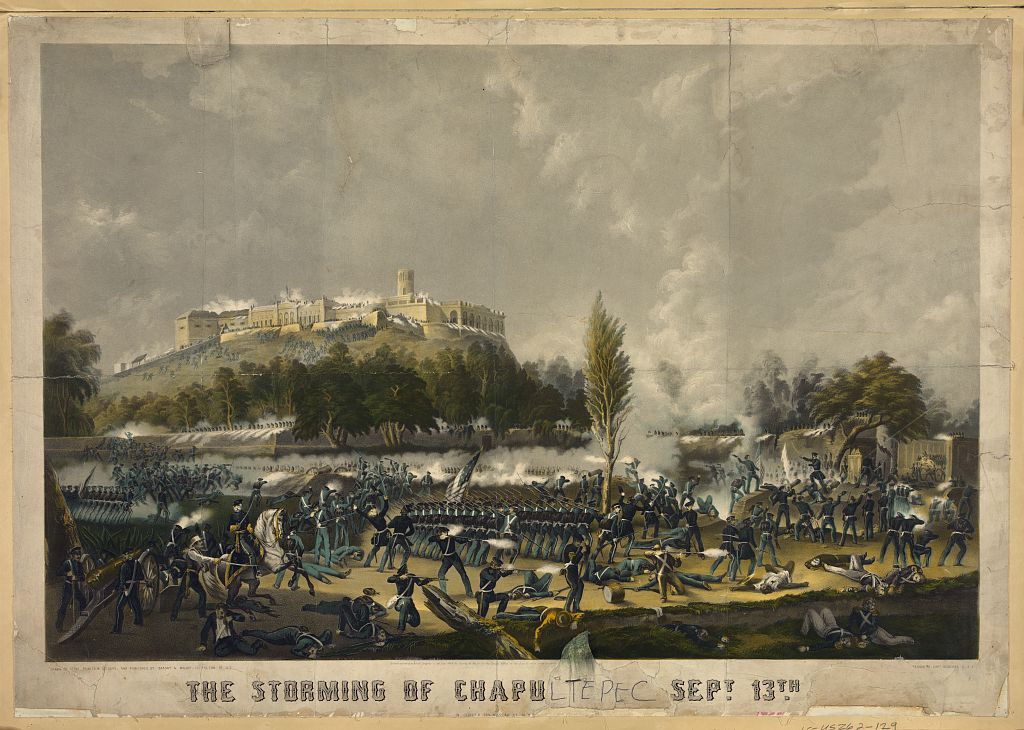

At 5:30 in the morning of Sept. 13, the American cannon opened fire. They kept up the bombardment until 8 a.m., when the infantry and Marines in the attacking columns, totaling some 7,200 men, surged forward.

The Americans began to climb Chapultepec’s Hill, clawing their way up as the Mexican musketry started to crackle out. That musketry tore the forlorn hopes apart. Captain Silas Casey, who would come to write a tactics manual in the 1860s, went down wounded. A bullet hit Marine Maj. Levi Twiggs, killing him. Grapeshot struck Gen. Gideon Pillow, breaking his ankle and putting the division commander out of action.[11]

To help out the foot soldiers, Lieutenant Thomas Jackson deployed two cannon in an open causeway and opened fire. The American shots soon attracted Mexican counter-battery fire, killing and wounding American gunners. “There is no danger,” Jackson called out to his crews. “See? I am not hit!” Historian James Robertson writes, “Later in life, he admitted that the statement was the only lie he ever knowingly told.”[12]

Though taking casualties at every step, the Americans kept up their advance, finally reaching the walls at the top of the hill. Using the scaling ladders, the Americans poured into the Mexican defenses. “We then dashed forward along the road,” D.H. Hill wrote, “and drove the Mexicans before us with great slaughter.”[13] Elsewhere advanced Lieut. James Longstreet, carrying the battle flag of the 8th U.S. Infantry. A Mexican shot struck him “in the thigh,” and he fell, handing the colors to Lieut. George Pickett.[14] Advancing into the center of Chapultepec’s walls, Pickett made his way to the flagstaff and sliced down the Mexican banner. Tying the Stars and Stripes to the halyards, Pickett lifted the flag to the sky. Mexican soldiers resisted the effort and Pickett later showed his cousin, Henry Heth, “where he scaled the wall and where he shot a ‘greaser,’ thus saving his own life.”[15]

The fighting around and inside of Chapultepec took about an hour from start to finish. It left a ghastly aftermath, with American surgeon Richard McSherry writing, “Heaps of dead and wounded blocked the approaches to the castle as we entered.” The surgeon continued, “Crushed heads, shattered limbs, torn up bodies, with brains, hearts, and lungs exposed, and eyes torn from their sockets, were among the horrible visions that first arrested attention.”[16]

Watching the fighting from the confines of Mexico City, Santa Anna, seeing the American flag, is said to have shouted out, “I believe if we are to plant our batteries in Hell the damned Yankees would take them from us.” Beside him, a subordinate supposedly replied, “God is a Yankee.”[17]

The fighting around Chapultepec was horrendous, as evidenced by Surgeon McSherry’s remarks. And in the middle of that chaos emerged two broader legacies, one for each country. At the beginning of the famed United States Marine Corps hymn, voices cry out, “From the Halls of Montezuma…,” commemorating the Marines’ advance against Chapultepec. And in Mexico, the lives of six young boys are remembered among the carnage of war. Students of the Mexican Military Academy, six cadets refused to leave Chapultepec, and as the Americans overwhelmed the castle, the six boys threw themselves off the summit of the hill. Their deaths are remembered as the los Niños Héroes (the Boy Heroes).

With the attack having started around 8 a.m., and finishing around 9 a.m., the day was barely getting started. And order soon broke down in the wake of the American victory at Chapultepec. Mexico City was within site, and it seemed like the American soldiers just had to reach out and grab it. Soon units, disorganized as they were from the attacks, began to press down the causeways leading into Mexico City. Those attacks would climax at two gates leading into the city. The question was: could the Americans re-organize and make the attacks successfully, or would they be repulsed with even more losses?

______________________________________________________________

[1] Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Fifty Years in Camp and Field: Diary of Major General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, U.S.A. Edited by W.A. Croffut. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 280.

[2] K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974), 313.

[3] Winfield Scott, Memoirs of Lieut.-General Scott (New York: Sheldon & Company Publishers, 1864), 510.

[4] Justin Smith, The War with Mexico, Vol. II, (New York: MacMillan, 1919), 149.

[5] Hitchcock, 301.

[6] Bauer, 312.

[7] RJack. C. Mason, Until Antietam: The Life and Letters of Israel B. Richardson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 57.

[8] Daniel Harvey Hill, A Fighter from Way Back: The Mexican War Diary of Lt. Daniel Harvey Hill, 4th Artillery, USA, ed. Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and Timothy D. Johnson (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2002), 125.

[9] Timothy D. Johnson, A Gallant Little Army: The Mexico City Campaign (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007), 218.

[10] Mason, 57.

[11] Johnson, 221; Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and Roy P. Stonesifer Jr., The Life and Wars of Gideon J. Pillow (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2011), 100.

[12] Jackson quoted in James I. Robertson Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1997), 66-67.

[13] Hill, 126.

[14] Jeffry D. Wert, General James Longstreet: The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Biography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 45.

[15] Henry Heth, The Memoirs of Henry Heth. Edited by James L. Morrison. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1974), 65.

[16] Richard McSherry, Essays and Lectures (Baltimore: Kelly, Piet & Company, 1869), 75.

[17] Bauer, 318.

Exciting reading ! Those “Los Ninos Heros,” statues though… don’t they offend American tourists?

ROFLMAO!

Hello. Do you think that the story of the cadets committing suicide is a myth?