Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 3

Part three in a series. Part One is here, and Part Two is here.

War had come, and the people of Herkimer County, New York answered. Located towards the center of the state, the New Yorkers soon heard of Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. “This was stimulated by sermons bristling a fiery and bayonet patriotism,” a Federal volunteer remembered forty-two years later. “The voice of the country was for war, and that of the most ruddy variety,” he continued. Out of Herkimer County came five companies of young soldiers who soon became part of the 34th New York Infantry. Since half of the regiment came from the same county, the 34th soon took on the nickname the “Herkimer Regiment.” They mustered in at Albany and soon made their way down South. They had a meeting with the Dranesville Home Guard in their future.[1]

The 34th New York arrived at Seneca Mills, Maryland on August 1, 1861. Located directly across from Virginia, the New Yorkers “now had custody of about seventeen miles of river front,” and were there to guard the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.[2]

The New Yorkers’ duties continued as the calendar crept towards fall. While the Union soldiers went on their patrols, they did not often see their Confederate foes. They certainly heard them, especially “drums and bugles,” at night when the riverfront was quiet. Confederates would only “occasionally show themselves” to the pickets along the Potomac, but little came of the encounters.[3]

The inactivity pushed the New Yorkers towards wanting to go beyond their usual patrols. Just across the river sat “the unknown land,” of Virginia, which became a “region of special interest and inquiry among both officers and men,” the New Yorkers’ historian wrote. “The fact that it was forbidden country, made it all the more interesting.”[4] Not condoned by their commanding officers, the New Yorkers started to send unofficial foraging parties across the river, especially targeting Lowe’s Island. An old channel of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal cut through the land, creating the island and making for an easy location to grab spoils.

On September 16, 1861, Capt. Wells Sponable received orders from the regiment’s commanding officer, Col. William LaDue. As Sponable explained later, LaDue “told me he had that day heard that a rebel regiment had recently been stationed at Dranesville, a small place, from four to six miles from our camp.” Sponable was ordered to “obtain all the information possible, and report as soon as practicable.”[5]

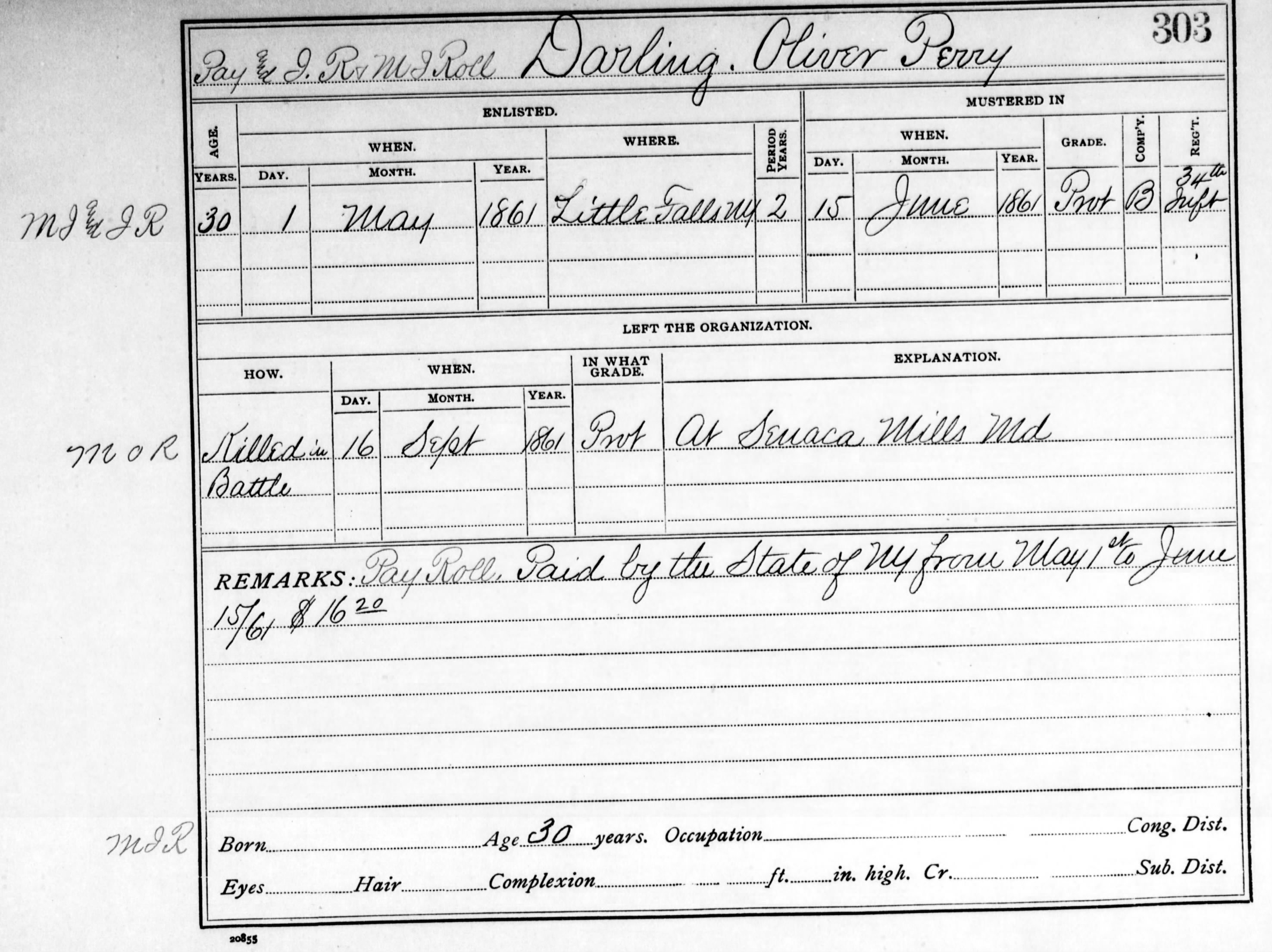

Sponable’s mission was supposed to be a quick reconnaissance, and thus the captain’s patrol was tiny in size. He was joined by Private Oliver Darling, of Sponable’s Company B, Private Robert Gracey, of Company H, and Corporal Christian Zugg, of Company D. As Sponable’s group set off across the Potomac, another “eight or ten members of our regiment,” also began to cross “on their way to obtain some of the rebels’ green corn on the island.”[6]

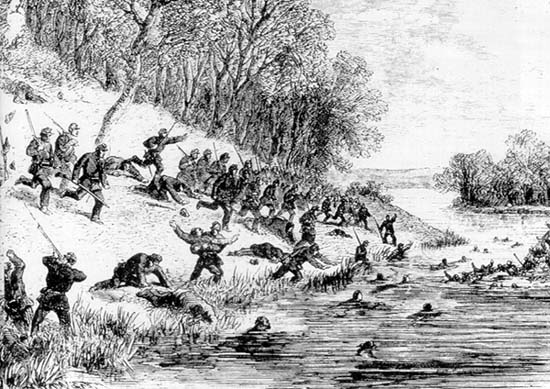

The party of twelve or so Federals crossed around sunset, about 6:00 p.m., and Sponable’s men set off to investigate the claims of Confederate activity in the area. As they advanced into Virginia, Sponable’s group took up stride in a single file. The Federals had advanced about half a mile from the Potomac, when, from the cornfield, Sponable remembered, “I heard a slight noise. . . probably not over three rods [about sixteen yards] distant from me.” Before the Federals could react, “Instantly thereafter I heard the command to fire given, which was followed by a volley of rifles.”[7]

The musketry sliced into the small patrol. Private Oliver Darling, from Little Falls, New York, died instantly. Robert Gracey, “a man of gigantic frame,” was struck by a musket ball that “entered near the left shoulder blade, and broke one of his ribs [then] glanced, and came out by the backbone,” sending the soldier tumbling to the ground. Behind them, a shot also found Christian Zugg, the ball grazing his face. Zugg reeled back to the Potomac, chased by Confederates, where he “plunged in himself, laying on his back and resting his head upon a stone, with his mouth and nostrils above the water.” He stayed there for the next three hours, avoiding detection, before being found by other Federal soldiers.[8]

In the chaotic first moments of the ambush, seeing both Darling and Gracey fall, Sponable thought they were both dead and began to make a quick retreat back to the Potomac River. He could hear Confederates quick on his heels and getting back to the river, he jumped in. Swimming across the Potomac, Sponable found the 34th New York drawn up in battle line, forming up in response to the shots in Virginia. An officer in the regiment recalled that he moved his company towards the Potomac “when whom should I meet but Sponable himself, with only one boot on.” Sponable had “Lost one boot, leggings, and revolver in swimming the river,” and the officer “could not help laughing at his ridiculous appearance.”[9]

Back near the site of the ambush though, the site was not laughable. Oliver Darling lay dead, Robert Gracey wounded, and the Confederates had managed to snag Corporal Cyrus Kellogg from the 34th, who had crossed as part of the eight men to grab corn and instead got captured in the confusion of the shooting.

As Gracey reeled from the wound to his shoulder, a Confederate walked up to him, leveled a pistol at the New Yorker, and fired. The bullet lodged in Gracey’s left lung, but still did not kill the Federal soldier.[10]

Leaving Darling’s corpse behind, the Confederates picked Gracey up and brought him and Corporal Kellogg further into Virginia. Their destination revealed the New Yorkers’ assailants: the citizens of Dranesville. Getting into town, the wounded Robert Gracey was sent to Charles Coleman’s store on the Leesburg Pike. Unhurt, Cyrus Kellogg was soon forwarded to a prison in Richmond. A commission of Union officers would later hear second-hand gossip that the secessionists in Dranesville denied Gracey’s request for water, calling him a “good-for-nothing Yankee.”[11] Gracey’s tribulations at Coleman’s store went on for almost two weeks. Somebody obviously tended to him because his two gunshot wounds did not fester or kill him.

Around this time Gracey also found out the identity of the man who had shot him after he was wounded: McCarthy Lowe, who owned the land that the New Yorkers had been raiding. It seemed that Lowe had gone to the Dranesville Home Guard and planned the ensuing ambush in retaliation for the New Yorkers taking corn and even horses from Lowe’s property.[12]

Dranesville’s Home Guard were quick to credit themselves for the ambush. Thomas Coleman bragged that he had killed Oliver Darling, and had even stripped Darling’s pockets, finding a letter that he read in the center of town. At the same time, William Day and Stephen Farr supposedly stripped Darling’s body naked and gave pieces of his uniform to their enslaved people.[13]

Gracey, still in Dranesville, later said that he paid an Irishman known only as Jimmy to go out and bury the dead from the ambush. Thinking both Darling and Capt. Sponable had died, Gracey paid Jimmy to bury two bodies—this would lead to confusion in the months to come, and even to this day. When the ambush at Lowe’s Island is mentioned, it is almost always said that two Union soldiers were killed—such was not the case—Oliver P. Darling was the only fatality on the night of September 16, 1861.[14]

After almost three weeks in Dranesville, being confined at Coleman’s store and then at William Day’s house, Gracey was moved to Fairfax Court House. There, the intuitive New Yorker made his escape. Every night a Confederate surgeon would see to Gracey’s wounds and gave the Union soldier a small amount of opium so that he could sleep peacefully through the night. Gracey hoarded the opium until he had enough to drug his guards’ coffee, and then, leaving “one of them sleeping at one door, and one at the other,” Gracey started to walk back towards the Potomac River. Evading capture and Confederate patrols, Gracey was pulled back into Maryland and heralded as a hero back in the camps of the 34th New York.[15] As Gracey told and retold the story of his wounding, capture, and imprisonment, there was little the 34th could do to retaliate. As part of Charles P. Stone’s command along the Potomac, they were readying for the operation that would culminate in the battle of Ball’s Bluff. And, even though Gracey had gotten some kind of an idea of who was behind the attacks at Lowe’s Island, he did not have a full or complete picture.

But, back at Dranesville, there were three enslaved people who did know the names and identities of the all the members of the Dranesville Home Guard. And one night, in the middle of November, 1861, they ran away, headed for nearby Union camps.

______________________________________________________________

[1] L.N. Chapin, A Brief History of the Thirty-Fourth Regiment, N. Y. S. V (N.p., 1902), 09.

[2] Chapin, 23.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Chapin, 23.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, 23-24; “The Affair of the Scouts of the 34th Regiment,” Unknown Newspaper Publication, 34th Regiment New York Volunteers Civil War Newspaper Clippings, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

[8] “From the Upper Potomac,” Unknown Newspaper Publication, 34th Regiment New York Volunteers Civil War Newspaper Clippings, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

[9] Chapin, 24.

[10] “The Dead Alive, And the Lost Found”, Unknown Newspaper Publication, 34th Regiment New York Volunteers Civil War Newspaper Clippings, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

[11] Cases Examined by Commission Relating to State Prisoners, William B. Day Case, NARA, 44.

[12] Unknown Newspaper Publication, 34th Regiment New York Volunteers Civil War Newspaper Clippings, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center; Cases Examined by Commission Relating to State Prisoners, John T Day Case, NARA, 35.

[13] William B. Day Case, 15-16.

[14] Chapin, 23; William B. Day Case, 17.

[15] “The Dead Alive, And the Lost Found”, 34th Regiment New York Volunteers Civil War Newspaper Clippings, New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center

1 Response to Dranesville: A Troubled Town, Part 3