One of Sherman’s Pioneers: The Story of Levi Lindsay

Born in Caton, NY, on November 15, 1839, Levi Lindsay was the second son of Allen Lindsay, Jr. (1810-1891) and Harriet Benson (1825-1860). He had four siblings: Horace (1837 – 1871), Charlotte (1844 – 1876), Hannah (1846 – 1860) and Helen (1849 – 1908).

Born in Caton, NY, on November 15, 1839, Levi Lindsay was the second son of Allen Lindsay, Jr. (1810-1891) and Harriet Benson (1825-1860). He had four siblings: Horace (1837 – 1871), Charlotte (1844 – 1876), Hannah (1846 – 1860) and Helen (1849 – 1908).

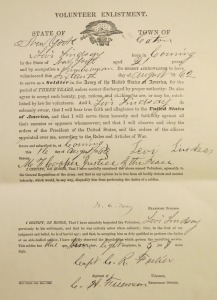

When the Civil War began, Levi was just 21 years old and working as a lumberman. In August 1862, young Lindsay enlisted in the Union army for a three year term in Company D, 141st NY Vol. Infantry. From his enlistment form we learn that he had blue eyes, brown hair, a light complexion and stood 5’ 8’’. His service began around Washington, DC before temporary duty at Suffolk, VA.

In July 1863, Lindsay’s regiment joined the 2nd brigade of the 3rd division, IX Corps, which was dispatched to Chattanooga, Tennessee to help General Grant lift the siege of the Union forces in occupation of the town. Taking part in the Battle of Missionary Ridge, Lindsay and the men of his regiment helped to break the Confederate hold on the ridge, ending the siege and sending Gen. Bragg’s rebel army in headlong flight into Georgia.

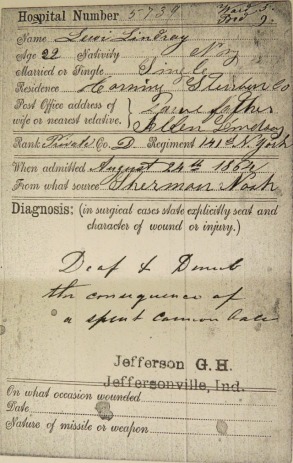

In April 1864, Lindsay’s regiment was joined to the new XX Corps. and followed Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman on his famous Atlanta Campaign. Approaching Kennesaw Mountain in June, Lindsay was wounded near Lost Mountain when a spent artillery part struck him leaving him “deaf and dumb” – according to the casualty report. After treatment in the division hospital in Chattanooga, he was sent to Jefferson General Hospital in Jeffersonville, Indiana, and admitted on August 24th. On August 29th he was discharged for regular duty. It is likely that Private Lindsay suffered from a moderate to severe concussion and ultimately would recover his hearing and speech. However, it probably affected his health for the rest of his life.

By the time Lindsay rejoined Sherman’s army in Georgia, the Union army had captured Atlanta (Sept. 2nd). A major Confederate rail hub and manufacturing center, Atlanta was an important Union victory that helped to secure the reelection of Abraham Lincoln. In mid-November, Sherman was off again. He sent Gen. Thomas and his army to Nashville, Tennessee, and he took 60,000 of his hardiest veterans on his famous march to the sea. With him would be Lindsay and the 141st NY. The young man from Caton moved in advance of the bulk of Sherman’s army as a pioneer, building bridges and laying corduroy roads all the way to Savannah, GA – arriving just in time for Christmas.

In January 1865, Sherman started his army north with the aim of eventually joining Gen. Grant in front of Petersburg, VA. His path of march would take him through the cradle of secession – South Carolina – before entering North Carolina and the Old Dominion. Once again Levi Lindsay and his company acted as pioneers, helping to forge a path through some very rugged country for the army to follow.

During the march to the sea and through the Carolinas there were few pitched battles to fight. As Sherman later explained, his campaigns in late 1864 and early 1865 were aimed at the Confederate will to fight. It was a cagey psychological game Sherman was playing – and it clearly worked. For much of his trek through Georgia and the Carolinas, the Confederates could do little to stop him. Confederate horsemen would snap at his heels here and there, but did little but annoy him and his army.

The last battle for the 141st NY was in North Carolina at the Battle of Averasborough on March 16th. Not heavily engaged, they did nonetheless lose a few men. A few days later Sherman’s army engaged in their last battle at the Battle of Bentonville, but the 141st was not engaged. Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Sherman April 26th, just a few weeks after Lee’s surrender to Grant in Virginia. Following Johnston’s capitulation the 141st and the rest of Sherman’s army made their way to Washington, DC at a leisurely pace. On May 24th the 141st took part in a “Grand Review” of the major armies of the Union before a large crowd waving flags and celebrating ultimate victory.

Lindsay was mustered out of the Union army on June 8th, 1865, near Washington, DC. His muster form noted that he was paid a $25.00 bounty and was still due $75.00. He probably stepped off a train onto a platform in Elmira within three days.

Incidentally, Levi may have arrived home at about the same time his father, Allen Lindsay, Jr., returned. The elder Lindsay did not enlist until September 1864, though he had tried to get into the war earlier. At fifty-four years old, he was far older than the average recruit and outside of the age of the draft entirely. It is likely that Allen was in dire need of money and probably wanted a change of scenery. He had lost his wife Harriet in 1860 and his daughter, Helen, described him as depressed from the loss. In any case, we know that Allen had to convince the provost marshal of his fitness to serve.

Unlike his father, Levi seemed to return home in decent health. Allen, on the other hand, was “a mere skeleton” according to his daughter, and suffered from chronic dysentery the rest of his life. Ironically, the elder Lindsay would however outlive his son by many years.

In May 1867 Levi married Adeline Stickler in Big Flatts. Born in 1844, Adeline was the daughter of George Stickler (1817-1858) and Rebecca Traver (1824-unknown) and was the widow of Levi’s uncle William Lindsay (1836-1864), who was killed in the Civil War at the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. (For folks of Rogers’ heritage, the surnames Stickler and Traver probably ring a bell. LaFayette Stickler’s (1866-1943) parents were Stephen Stickler (1828-1899) and Susan Traver (1824-1909). It is likely that Adeline’s family line and the Campbell Sticklers probably intersect somewhere, though I have not developed that yet.)

Levi and Adeline settled down in Caton at first and later Elmira. They would have five children: Sara, Ella, Frederick, Maynard and Avery. In August, 1876, Levi died at the age of thirty-six. We do not know the cause of death, but it is not unreasonable to wonder if the traumatic head injury he suffered in the Atlanta Campaign was related somehow. His place of burial is unknown. Adeline would remarry and survive until 1929.

1 Response to One of Sherman’s Pioneers: The Story of Levi Lindsay