The Emancipation Proclamation: An International Turning Point

In his post “Thenceforward and Forever Free”: The Emancipation Proclamation as a Turning Point, Dan Vermilya makes a good case that the president’s executive action was a turning point of the war because it clarified Union war aims on the issue of slavery.

In his post “Thenceforward and Forever Free”: The Emancipation Proclamation as a Turning Point, Dan Vermilya makes a good case that the president’s executive action was a turning point of the war because it clarified Union war aims on the issue of slavery.

The proclamation was equally crucial in another—frequently neglected—international arena: it inspired Great Britain to stay out of the conflict. In 1862, the British administration was under intense political pressure to intervene. A significant portion of the public opinion that mattered was sympathetic to the South. Why such affection for the Confederacy?

One factor was lingering resentment over the Revolution, only eighty years past, and over the petty fuss ignited in 1812 while Great Britain was embroiled in a death struggle with Napoleon. British elites also disdained what they perceived as arrogance, condescension, and bad manners of former colonists, their incessant boasting about strength, freedom, democracy, and destiny.

One factor was lingering resentment over the Revolution, only eighty years past, and over the petty fuss ignited in 1812 while Great Britain was embroiled in a death struggle with Napoleon. British elites also disdained what they perceived as arrogance, condescension, and bad manners of former colonists, their incessant boasting about strength, freedom, democracy, and destiny.

And despite the 1846 repeal of the British Corn Laws (which erased the last vestiges of mercantilism, ensured the triumph of free trade, and inaugurated a surge of prosperity), the unenlightened United States clung to protective tariffs. This also was a long-standing complaint of the agricultural South.

But enthusiasm for the South also was genuine and positive. From across the pond, aristocrats and wealthy upper middle classes saw little of the South beyond the Virginia and Carolinas of Revolutionary familiarity, and were largely ignorant of the explosion in northern industry and transportation. Through summer 1862, British newspapers reported almost exclusively Southern victories.

The government of Jefferson Davis, noted one Briton, “spoke little and hit hard, came forth calm in adversity and modest in success, kept its eye fixed on its purpose, and strode towards it with resolute step.” Unlike Washington, Richmond behaved with dignity, “a countenance stern and haughty, a quiet air, absence of ostentation and brag.” The English were more inclined to advocate a bad cause defended in proper form than a good cause badly defended.[1]

Prime Minister Palmerston once remarked to a Confederate representative: “The common idea of England is that the Southern people are more like us in character than the Yankees, who have too much of the old Puritan leaven in them to suit us. You Southerners we consider only as transplanted Englishmen of the old stock.”[2]

Many accepted the South’s mythology. Rebels were fighting with fortitude and resolution for freedom under men cut from the same cloth as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, paragons of military genius, courage, patriotic valor, and sacrifice—men like the urbane Jefferson Davis (and in stark contrast to a bumbling frontiersman like Abraham Lincoln).

Robert E. Lee ranked with Wellington among the great generals of English blood; the death of Stonewall Jackson caused an extraordinary outpouring of grief; victories of the Confederate commerce raider, CSS Alabama, were cheered in the House of Commons.

There were of course those abroad who—for politics and/or profit—took satisfaction in the war and potential breakup of the Union. However, most British desired an end to this insane American conflict for national interests as well as for humanity and compassion; a prolonged war would devastate both sections along with Atlantic commerce.

International law permitted intervention by neutral nations to prevent irreparable harm in their own interests. The British people were not required to stand by as witnesses to economic chaos and political unrest in their homeland caused by other peoples’ quarrels. That summer, British ministers and Parliament seriously debated all options from mediation to mandated arbitration, with force if necessary, which almost certainly would have led to Confederate independence. No one doubted they had the navy to do it.

Perhaps the core misapprehension of the British (and foreigners generally) existed over causes. In the first place, the mystical concept of union advanced so eloquently by Abraham Lincoln had little resonance for a people with no experience of a written constitution or a federal system. Their constitution consisted of venerated institutions inherited from the mists of time, not a single document or an overarching principle. They were unified by history and by ethnicity, religion, and geography.

Elites seriously doubted that the strange structure cobbled together in 1787 would work and were not altogether disappointed to see it in trouble. Unlike a constitutional monarchy, large, democratic republics could not endure. They would either disintegrate or descend into tyranny as had Athens, Rome, and most recently, France.

British elite opinion also exhibited a nascent ambivalence toward their empire flourishing in Africa and Asia. While intensely proud of these accomplishments, many concluded that the Declaration of Independence may have been correct in some sense.

The United States was a child of England and had been an immense success, in which, despite differences, they could take great satisfaction. Perhaps the natural course of civilizing influence in overseas enterprise motivated colonies toward independence in a modern commercial and industrial world. It behooved them to accept and support this pattern of self-determination, not fight it.

The British sympathized with Greek and Italian freedom and supported independence for Spanish American colonies and Belgium. Their experiences in North America and the West Indies demonstrated the burdens as well as the benefits of colonial rule. But in stark contrast, the United States continued to grasp at empire by acquiring Louisiana, annexing Texas, grabbing the Southwest, brutally suppressing Indians, and, not coincidentally, threatening British Canada.

And finally, there was slavery. The British hated the institution. They had been the first society in human history to engender a broad moral consensus against involuntary servitude as antithetical to foundational principles. They were the first to officially outlaw it (1833) after a long, desperate struggle, despite severe political and economic consequences.

British abolition was a primary inspiration for American abolition, and an excellent reason not to favor the Confederacy. However, not perceiving President Lincoln’s domestic constraints, the British were confounded when for a year and a half he maintained that the war was not about slavery.

So, if union did not make sense, if independence was a natural consequence of colonial maturity, and if slavery apparently was not the issue, this war must be about conquering a people who wished to left alone.

Lord Acton wrote to Lee complementing him for fighting the battles of English freedom and civilization, concluding: “I morn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.” A cause fought for so valiantly by such men must be a just one. The Confederacy was the true champion of freedom (as opposed to equality, which these men did not favor).[3]

Eighty years ago in America, rightful rulers had been despised and rebels honored; now rebels were traitors. As insistently argued by Southerners, why shouldn’t the Confederacy do to the United States what the colonies had done to Great Britain? These were natural rights of revolution, freedom, and consent of the governed.

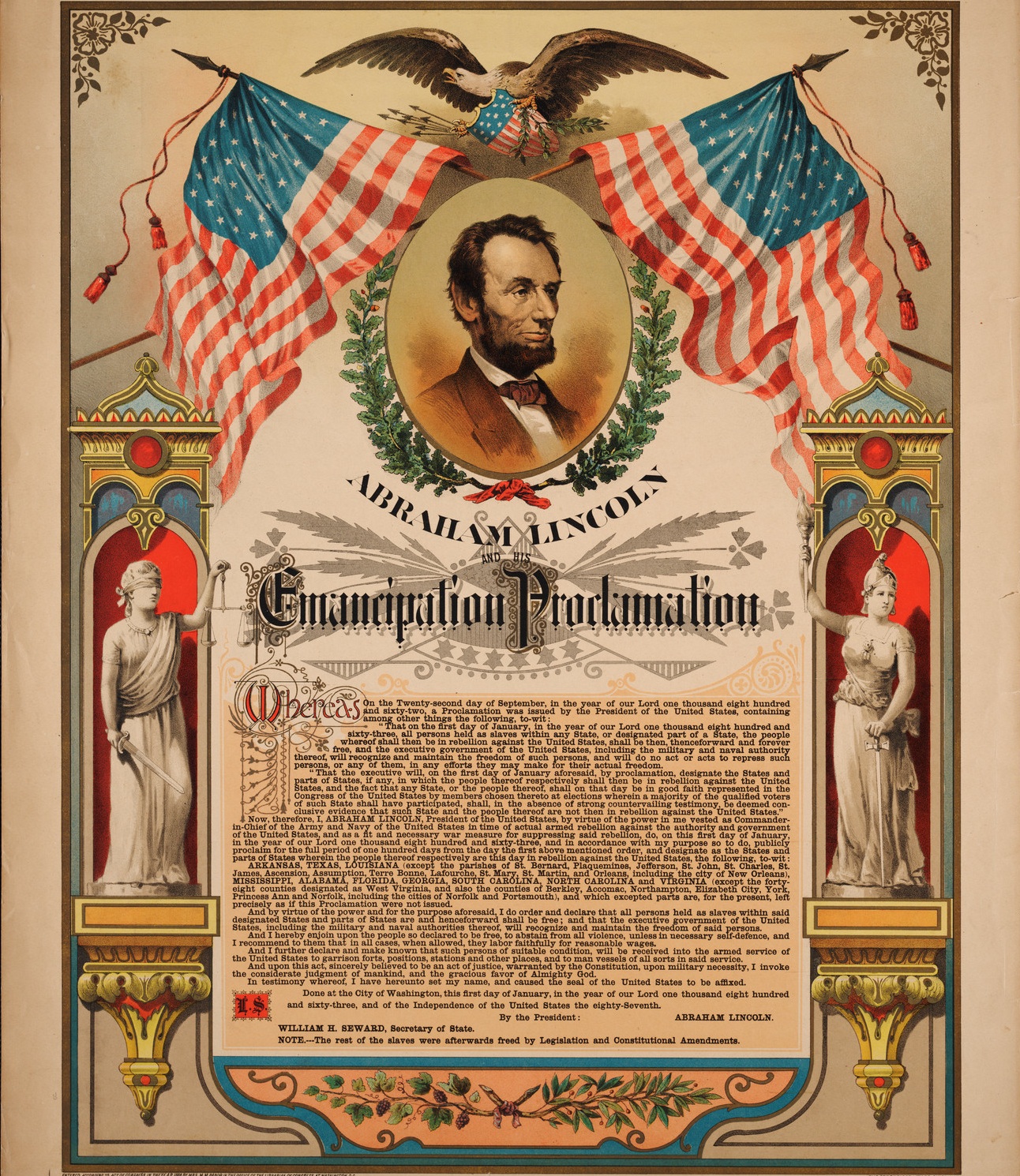

Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward were intensely concerned with countering this insidious line of thought. So, one of Lincoln’s primary motivations for the Emancipation Proclamation was to convince the British that the issue of slavery was indeed central to the war effort, and to discourage talk of intervention aimed at ending the conflict with anything less than total Union victory.

However, in a prime example of international misunderstanding, many Britons initially concluded that the proclamation was not a moral position, but a self-serving act of military desperation that could—perhaps intentionally—start a race war. Confederates, of course, adamantly agreed. Yankee hypocrisy on the subject was reinforced by pre-war complicity in the illegal slave trade, continued existence of slavery in border states, and now the narrow and selective application of emancipation.

The British did not, as Lincoln did instinctively, see a connection between preserving the Union and the end of the institution. In fact, many believed that Confederate independence would more rapidly extinguish slavery by isolating it in the south. Emancipation in the West Indian sugar plantations had been necessary and proper, but also an economic disaster and a bitter experience.

From a distance, Confederate rationalizations had made sense: slavery would be ended in their own good time, not as forced upon them by northern tyrants, and child-like Africans would benefit with enlightened, gradual freedom from kindly and paternal care.

But after Antietam and promulgation of the draft proclamation, the British paused their frantic debates and tabled decisions on intervention. The Emancipation Proclamation was a major and crucial first step, resetting the terms of discussion from then on. Confederate reverses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg the next summer accelerated the process, effectively ending serious discussion of the subject. The British would stay out. The Confederacy would sink or swim on its own.

Sources:

Vanauken, Sheldon. The Glittering Illusion: English Sympathy for the Southern Confederacy. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1989.

Jones, Howard. Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Mahin, Dean B. One War at a Time: The International Dimensions of the American Civil War. Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, 1999.

Merli, Frank J. Great Britain and The Confederate Navy, 1861-1865. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

[1] Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion, 62.

[2] Jones, Blue & Gray Diplomacy, 158.

[3] Vanauken, The Glittering Illusion, 103.

Dwight:

What a great New Year’s gift you gave us Emerging Civil War readers! Your post is well written and very informative. One suggestion: Your list of sources did not include Our Man in Charleston by Christopher Dickey. If you haven’t read it yet, you should. It helped me understand the dynamics of British diplomacy regarding the Confederacy.

Again, great post.

Thanks Bob. Good suggestion. Just ordered a copy. Happy New Year!

Great information, Dwight. As a fan of very old books, I read a historical fiction story about the Civil War written in England a couple decades after the war ended; its perspective is interesting and rather one-sided (pro-Southern). Your article helps me understand some of the viewpoint and details in the story.