Identifying “Courier Kirkpatrick” on A.P. Hill’s Last Ride

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill was killed in the aftermath of the successful Union attack near Petersburg on the morning of April 2, 1865. Sergeant George Washington Tucker, Jr., the general’s chief of couriers, was the only Confederate present at the time. Both Tucker and John Watson Mauk, the corporal in the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry who killed Hill, wrote lengthy descriptions of the event. Several other Confederates accompanied Hill for smaller phases of his last ride and they provided additional details of the journey. In all the accounts, both primary and secondary, a courier named Kirkpatrick is referenced. Until now he has only been referred to by his last name. Thanks to the recent digitization of historical records and newspapers, we can finally put a full name and additional information together on one of Hill’s companions during the final hour of the general’s life.

Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill was killed in the aftermath of the successful Union attack near Petersburg on the morning of April 2, 1865. Sergeant George Washington Tucker, Jr., the general’s chief of couriers, was the only Confederate present at the time. Both Tucker and John Watson Mauk, the corporal in the 138th Pennsylvania Infantry who killed Hill, wrote lengthy descriptions of the event. Several other Confederates accompanied Hill for smaller phases of his last ride and they provided additional details of the journey. In all the accounts, both primary and secondary, a courier named Kirkpatrick is referenced. Until now he has only been referred to by his last name. Thanks to the recent digitization of historical records and newspapers, we can finally put a full name and additional information together on one of Hill’s companions during the final hour of the general’s life.

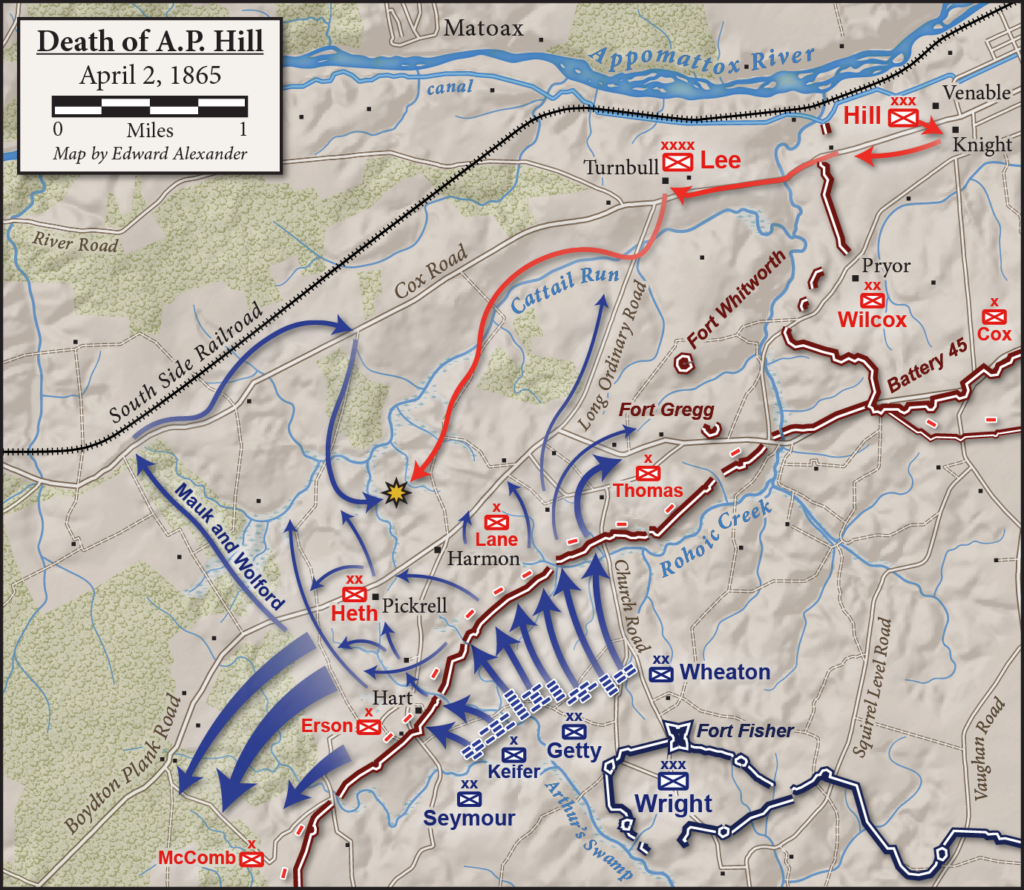

That morning, Hill left his corps headquarters at the Widow Knight house, “Indiana,” on Petersburg’s western outskirts. At the time he only suspected that Union forces had attacked somewhere along the Confederate lines and remained uncertain as to the exact location or results. Somehow the Third Corps commander discovered that his own lines had been broken during his mile-and-a-half route west to army headquarters at the Turnbull house, “Edge Hill.” How Hill found out is still a mystery.

The general had initially raced toward Robert E. Lee’s headquarters alone that morning, directing Colonel William Henry Palmer, his chief of staff, to remain at “Indiana” awaiting further orders. Hill instructed Tucker, his chief courier, to follow him to relay messages but the sergeant was in the process of grooming his horse and would be delayed while fixing the saddle. Headquarters protocol, however, required that two couriers always keep their horses prepared. Tucker beckoned to the current pair on call, Jenkins and Kirkpatrick, to follow the general and chased off after the trio several minutes later. Privates William Henry Jenkins and Kirkpatrick reached Edge Hill shortly after their general. Hill had seemingly become aware of the break in his lines during this ride and immediately directed Kirkpatrick to return to Widow Knight’s with a message for Palmer. The chief of staff was to head toward Wilcox’s lines and assist in rallying the scattered men.

The courier galloped off to bring the first news of the breakthrough to corps headquarters. Tucker afterward wrote that he passed him on the road “going at full speed.” Hill meanwhile climbed off his horse and entered the Turnbull house to converse with Lee and Lieutenant General James Longstreet. He soon rode onward, shedding his escort until only Tucker remained. After Kirkpatrick delivered Hill’s message to Palmer, the colonel immediately mounted and rode to Major General Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox’s headquarters at “Cottage Farm.” Wilcox commanded the division whose lines had been broken and Palmer warned him about the successful Union attack before continuing across Rohoic Creek toward the Whitworth house. Palmer wrote that Kirkpatrick followed behind him but did not provide any more information about the courier.[1]

Major General William Mahone’s Third Corps division had camped on the Whitworth farm during the winter before garrisoning the Confederate line at Bermuda Hundred, in between Petersburg and Richmond. Their vacated winter quarters afterward housed a few invalid soldiers, but Palmer now noticed Union soldiers lurking in that vicinity. He carefully picked his way toward the Long Ordinary Road—a small road that connected Boydton Plank Road with Cox Road. There he met Sergeant Tucker, alone, who told him that A.P. Hill had been shot.

The details of Hill’s death are well documented and will not be dissected here. The best place to find them is in the accounts of Tucker and Mauk, found in Volume 27 of the Southern Historical Society Papers. Readers can also consult Bud Robertson’s Hill biography—James I. Robertson, Jr., General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior (New York: Random House, 1987) and Will Greene’s narrative history of the last week at Petersburg—A. Wilson Greene, The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2008).

In the meantime, Wilcox had jolted into action. He immediately launched a counterattack that blunted any further expansion of the breach toward Petersburg before settling into a defensive position near Rohoic Creek. Brigadier General Nathaniel Harrison Harris’s Mississippians meanwhile rushed toward Forts Gregg and Whitworth. They belonged to Mahone’s division and were familiar with the ground but provided the lone reinforcements that Mahone could spare from Bermuda Hundred. Nevertheless, Wilcox’s attack and Harris’s defense bought time for Longstreet’s First Corps to arrive from Richmond in the early afternoon to garrison Petersburg’s inner defenses. Though the Confederates abandoned both cities overnight, the lack of a complete breakdown on Petersburg’s western front that morning perhaps extended the life of Lee’s army by another week.

Since then, no historian has produced more details or even a full name for the courier who first accompanied Hill and relayed the last message the general directed to corps headquarters. Who can blame them? Kirkpatrick was not present with Hill when Mauk shot the general, did not write an easily identified firsthand account, and though his message to Palmer had important consequences it could have been delivered by any mounted soldier. Furthermore, before modern research methods allowed keyword searches through historic records and newspapers, an effort to track down more information on Kirkpatrick would be a wild goose chase not worthy of the time commitment.

My search for the courier’s identity began with published primary accounts and secondary narratives. Those which identified him did so only with his last name. The next best reference place would be among the paroles of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. As a member of the corps staff, Kirkpatrick should be expected to have remained with the army through the last week of the war. Volume 15 of the Southern Historical Society Papers contains a list of parolees and a search for Kirkpatrick identified a “Private W.P. Kirkpatrick, Courier at Corps H’d Q’rs, one private horse.”[2]

One problem, however. That Kirkpatrick is listed as belonging to the 8th Tennessee Infantry, a regiment that would have been with Joe Johnston in North Carolina at the time. Furthermore, I used Fold3.com to browse through the service records for the 8th Tennessee and could not even find a W. Kirkpatrick. Perhaps at least the state and initials were correct. Fortunately for my search’s sake the Army of Northern Virginia only contained one brigade of Tennessee infantry, commanded at the end of the war by Brigadier General William McComb. They served in Major General Henry Heth’s division of the Third Corps and would have been located just a mile south of the point of the initial VI Corps attack on April 2, 1865.

In addition to the 2nd Maryland Infantry Battalion, McComb’s brigade included the 1st (Provisional), 7th, 14th, 17th, 23rd, 25th, 44th, and 63rd Tennessee regiments. In searching their records, I soon found a probable match in a soldier who shared the initials listed in the Southern Historical Society Papers parole list. Private William Pat Kirkpatrick, 7th Tennessee Infantry, was at Petersburg on April 2nd. His records show that he was captured on that day, held at Fort Delaware, and then released on June 28, 1865. Nothing, however, indicated that he was ever a courier or detached on any special detail.

I noticed several other members of the 7th Tennessee with similar names and started browsing their records. While clicking through Fold3’s muster roll cards for a William B. Kirkpatrick, Company E, I see “On extra or daily duty as Courier for Gen. Archer since 5 Oct 1862.” A few more clicks and I find “Detailed as Courier for Gen. Hill since 20 July 1863.” I continue through the end of William B.’s record and find him identified on the roll of prisoners paroled at Appomattox. “Remarks: Courier at Corps Hd Quarters and owns one horse.” Looks like a typo misidentifying his regiment in the Southern Historical Society Papers helped contribute to the courier being lost to history. I have his name now—William B. Kirkpatrick—what can we find out about him?

The service records simply show that he enlisted in Nashville on May 21, 1861 and served in Company E, 7th Tennessee Infantry. He was elected 2nd corporal on April 26, 1862, while the company was at Yorktown, Virginia, and then assigned as a courier for Brigadier General James Jay Archer, commanding the brigade, on October 5, 1862. Archer was captured at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, and held prisoner for over a year. Shortly after his return to the Army of Northern Virginia, Archer died on October 24, 1864. The general’s capture at Gettysburg deprived Kirkpatrick of his assignment, but he was detailed as a courier for A.P. Hill, commanding the Third Corps, on July 20th. Though his records do not identify a date or reason, Kirkpatrick was reduced to private before January 23, 1864. He nevertheless continued running messages for Hill until April 2, 1865.

There’s a brief synopsis of Kirkpatrick the soldier, but what more can we discover? I still did not have an age or a hometown, believing that Nashville could very well be just the place where he joined his company. Having exhausted Fold3, it was onward to digital newspaper databases. My favorites are the Library of Congress’s Chronicling American and Newspapers.com. A few keyword searches there produced obituaries for several Tennessee residents named William B. Kirkpatrick but those proved to not be the courier. But I’ve found with keyword searches that you need to take the time to include all possible name combinations. That means searching William Kirkpatrick, William B. Kirkpatrick, Wm. Kirkpatrick, Wm. B. Kirkpatrick, W. Kirkpatrick, W.B. Kirkpatrick, Will Kirkpatrick, Bill Kirkpatrick, and so on.

Searching for Wm. B. Kirkpatrick finally produced a hit. “In Memory of Wm. B. Kirkpatrick”—a letter written by a Jesse Cage to the editor of the Nashville Tennessean. It appeared in print in the May 4, 1908 issue. “Dear Sir—It is always sad to chronicle the death of a friend and more especially so when the friendship has been cemented and bound by all the ties incident to soldiers’ lives, who were closely associated together through the late war, who were on the Confederate side, where hardships and sacrifice were intense and were an excellent test of manhood.”[3]

Cage identified Kirkpatrick as a member of the 7th Tennessee Infantry and a courier for Hill’s staff. He also wrote that Kirkpatrick died in Weatherford, Texas. We’ll look more at the rest of Cage’s letter later in this article, but for now we have an approximate date and location of Kirkpatrick’s death. I could now consult another online resource, FindAGrave.com. Once again, a precise search for “William B. Kirkpatrick, died 1908, buried Weatherford, Texas” did not turn up anything. But a broad search for “W Kirkpatrick, died 1908, buried Texas” produced a headstone in the Greenwood Community Cemetery, Parker County, Texas, for a W.B. Kirkpatrick, born April 30, 1842, died April 29, 1908. Buried beside him is a Nettie Kirkpatrick, listed as his wife, born January 1, 1849, died June 12, 1935. Google Maps confirmed that the cemetery is located in Weatherford.

Now that I have a birth date, death date, burial location, military record, and spouse for Kirkpatrick, I could head over to Ancestry.com and plug those details into a search. There were a few matches in user-generated family trees but I prefer to avoid those until the end. Sometimes you can find worthwhile material in photographs, newspaper clippings, and family stories that other members of Ancestry upload, but it is wise to save this until you’ve developed a fuller picture on the individual you are researching. This enables you to properly screen out misleading or inaccurate information.

Included among Confederate pension records I found an application from a Nettie Kirkpatrick of Weatherford, Texas, filed November 19, 1913, and approved December 1, 1913. This digitized record confirmed all the previously identified information on William. It also provided a middle name, Bennett; a marriage date and location, November 12, 1874, Sumner County, Tennessee; Nettie’s full name, Eunetta R. Hunter Kirkpatrick; and an approximate year of their move to Texas, 1889. Nettie also testified that in addition to his early service in the 7th Tennessee, William “Was a Courier part of the time, was with Gen’l. A.P. Hill when he was killed and was at Gettisburg [sic] and all of the great battles… Mounted as a Courier for Gen’l Hill and Gen’l Longstreet.”[4]

Several of William’s former comrades provided statements on Nettie’s behalf. S.O. Cantrell wrote that he was a schoolmate of William’s in Gallatin, Tennessee, served with him in the 7th Tennessee Infantry, and that William served on Hill’s staff and then transferred to Longstreet’s. “There was no better soldier in Gen. Lee’s command than W.B. Kirkpatrick during the whole war,” Cantrell testified.[5]

The previously mentioned letter to the Nashville Tennessean had similarly praised Kirkpatrick. Jesse Cage served as sergeant in Company E, 7th Tennessee Infantry, and was wounded and captured during the Breakthrough on April 2, 1865. He wrote that William went by the nicknames “Fancy” and “Billy Kirk” and reflected on William’s character in his eulogy.

“His courage was unimpeachable, not of the kind which was foolish or for display, but was prompted by the noblest impulses of the heart, the thoughtful kind which carried him into the thickest and most dangerous places with no fear of consequences as to his own person. No message was ever placed in his hands, verbal or otherwise, but which was born to its destination, regardless of the dangers or hazards to his own life, and that, too, because of his high ideas of duty to the cause in which he was engaged. He had a kind, benevolent heart, full of compassion; his disposition was of the sunny kind, and his bearing always that of a gentleman.”[6]

Cage’s heartfelt letter included an incorrect rumor about Hill’s death as well as certainly false details about Kirkpatrick. “Gen. A.P. Hill was wickedly slain after he had surrendered, so I have been informed, and ‘Fancy’ killed the federal who did it.”[7]

The accounts of both Mauk and Tucker disprove the rumor that Hill was killed after surrendering. As to Cage’s assertion that Kirkpatrick killed Mauk, neither Mauk nor Daniel Wolford (the other Union soldier present at the time) were killed on April 2nd. They lived until 1898 and 1908 respectively. Colonel Palmer also wrote that Kirkpatrick was near him at the time of the general’s death. I’ll trust that more than Cage’s secondary claim. Because no one else placed Kirkpatrick with Hill at the time of his death, I also think we can safely interpret Nettie’s claim fifty years later that he “was with Gen’l. A.P. Hill when he was killed” to mean that William was present on his staff that morning.

However, I’m no longer surprised to see such far-fetched renditions of the event as Cage’s. After the war many veterans claimed to have been present. I’ve identified at least half a dozen unsubstantiated claims from Confederates who claimed to have been along Hill’s route, most of whom claim to have had the last conversation with the general. Even more Union soldiers claim to have fired the shot that killed the general. One must utilize a critical eye when consulting Civil War resources, but I am satisfied with confidence that we can close the book on Private William Bennett Kirkpatrick, courier for Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill.

————

[1] George W. Tucker, “Death of General A.P. Hill,” Southern Historical Society Papers (Richmond, VA: Published by the Society, 1883), Volume 11, 566. William H. Palmer to Murray F. Taylor, November 8, 1902, Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park.

[2] Southern Historical Society Papers (Richmond, VA: Published by the Society, 1887), Volume 15, 288.

[3] Jesse Cage to “Editor The Tennessean,” May 2, 1908, “In Memory of Wm. B. Kirkpatrick,” Nashville Tennessean, May 4, 1908

[4] Nettie Kirkpatrick, Pension Record, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, accessed through Alabama, Texas, and Virginia, Confederate Pensions, 1884-1958, Ancestry.com.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “In Memory of Wm. B. Kirkpatrick,” Nashville Tennessean, May 4, 1908.

[7] Ibid.

Sterling detective work !

Edward:

Sherlock Holmes couldn’t have done any better.

Congratulations sir. Another piece of the Civil War puzzle put into place. Your determination to identify this man is amazing. I really enjoyed the article. Well done sir.

And this is why you are a Civil War rock star.

Great stuff Edward!

The W. B. Kirkpatrick , about who you have written, is my Great Grandfather. My father and older brother have proudly proudly carried his name forward. He enlisted in Co. E of the 7th Tennessee Infantry in May of 1861 and served in the Confederate Army until he was paroled at Appomattox, Va.in April of 1865. Upon his death on April 29, 1908, he was buried with full CSA Military Honors in Greenwood Cemetery in Weatherford, Texas.