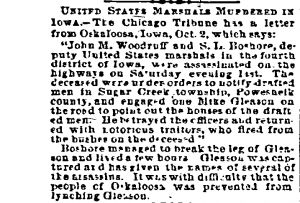

Draft Dilemma in Poweshiek County: The Murder of the Marshals

Emerging Civil War welcomes guest author David Connon

Amid mounting Union Army death counts in summer 1864, Iowa had its first draft. Three men didn’t report for duty on October 1, so the provost marshal in Grinnell sent two deputy marshals to southern Poweshiek County to round up the draft deserters. Bushwhackers murdered the marshals. As the second marshal lay dying, he named the murderers. The killings occurred in an atmosphere thick with fear, that could be traced back to the firing upon Fort Sumter.

Many Iowa Republicans and Democrats had enlisted after Fort Sumter, but many peace-minded Democrats feared a draft. Some conscription-eligible men considered moving to Canada. As the war continued, outraged Republicans blasted Democrats who dissented against the war, President Lincoln, and (as the war progressed) emancipation. Congressional candidate J.B. Grinnell (who the town of Grinnell was named after) worried about Iowa’s southern border with slave-holding Missouri. He wrote Gov. Samuel J. Kirkwood in August 1862: “Secret Societies are being organized to defy the draft and collection of taxes. The traitors are armed. Our soldiers are defenseless. We want arms. Can we not have them?”

The next year, in July 1863, thousands fell in hails of bullets at Gettysburg. The Lincoln administration quickly enacted a draft, but it didn’t yet affect Iowa (which had high numbers of volunteers). Conscription sparked several days of deadly race riots in New York City.

Outspoken editors of dissenting Democratic newspapers denounced the federal government’s tactics. The Muscatine Courier wrote, “Let Mr. Lincoln withdraw his emancipation proclamation and there will be no more riots in New York or elsewhere, occasioned by resistance to the draft.” John Gharkey of the Fayette County Pioneer told Iowan men in September 1863: “You should resist the conscription with your rifles, your shotguns, or whatever weapons you get hold of. If you, young men, do not resist conscription, you are unworthy to be called American citizens.”

Words turned violent outside South English, Keokuk County, Iowa, on August 1, 1863. Gun-toting Peace Democrats, led by Reverend Cyphert Tally, passed through the heavily Republican town. Fiery words flew, gunfire erupted, and Talley dropped dead. His supporters rallied at the Skunk River, some 16 miles away, drawing friends from Poweshiek and other counties. Governor Kirkwood sent in six militia companies, and the mob disappeared.

The next governor, William M. Stone, responded to Tally’s death (and the New York City draft riots) by calling in January 1864 for “loyal men” to “preserve the peace of the state.” Volunteer militia companies in every county were “promptly organized … of loyal and substantial citizens.” This action later bore deadly fruit in Poweshiek County.

As the war continued, Democrat fears of a growing war machine – and opportunities for negroes — became a reality. On Feb. 1, Congressman J.B. Grinnell introduced a resolution to encourage Negroes to enlist in the Union army.

President Lincoln told Grinnell, “I am glad that Congress has endorsed the policy of actively enlisting black men … It is a great day for the black man when you tell him he shall carry a gun … it foretells that he is to have the full enjoyment of his liberty and manhood.”

Lincoln concluded: “Now, tell your people in Iowa … the time has come when I am for everybody fighting the rebels. Let Indians fight them; let the negroes fight them; and if you have got any strong-legged jackasses in Iowa that can kick rebels to death, they have my hearty consent.”

Southern-sympathizing congressmen described Grinnell as being ‘drunk with blood.’ Grinnell retorted that Democrats were “in league with slavery and the Devil.”

In early May, Union troops entered the Wilderness Campaign. Turning his face like flint toward Richmond, Grant said he would “fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Over the next six weeks, more than 60,000 Union soldiers died, were wounded, or missing. Meanwhile, Sherman’s troops moved toward Atlanta.

The war came home to Grinnell when Provost Marshal James Mathews quietly announced a draft. Grinnell Republican men formed a militia and began to drill. Mathews, located in Grinnell, “spoke of the necessity of dealing with severity with the rebel sympathizers at the north.”

Fourteen miles south of Grinnell, men formed a militia in Sugar Creek Township. That part of the county had most of its southern-born population. Elizabeth D. Williams, wife of a Union Army soldier, said the neighborhood “contained numerous sympathizers with the South,” and she said they harassed her, killed their cows, and destroyed other property.

The Sugar Creek militiamen called themselves the “Democratic Rangers.” Said to be Democrats, its members took an oath to support the United States Constitution and the State of Iowa — but with a twist. They reportedly “would resist the draft … shoot any Marshal or officer who would come for them … and assist the rebels if they should come into Iowa.”

The fifty or so Democratic Rangers drilled twice in September 1864. Many of them carried arms. In mid-September, Provost-Marshal Mathews issued draft notices to three of them, requiring them to appear in Grinnell by September 30. One draftee, Joseph Robertson, said that if he were forced into the army, he would “shoot the officers.”

Democratic Ranger Michael Gleason, a native of Ireland, said he was “not in favor of forcing men to fight in a nigger war.” He bragged that “if the Marshals came to Sugar Creek Township to take men, he was ready to help kill them.” He added, “If the Marshals came into Sugar Creek township to take men out, he … had plenty of backing.”

The draft deadline passed, and on October 1, Provost Marshal.Mathews sent Deputy Marshal John L Bashore and Special Agent Josiah M. Woodruff to locate and arrest three draft deserters. Bashore and Woodruff rode a buggy into Sugar Creek, unaware that the Democratic Rangers planned to drill that afternoon.

The marshals began looking for draft-deserter (and South Carolina native) Samuel A. Bryant. Two brothers, John and Joe Fleener, rode up to the marshals, opened fire, and killed one instantly. A third bushwhacker, Irish native Michael Gleason, ran up and started hitting the surviving marshal in the head with a rifle. Someone shot Gleason in the leg during the melee. The Fleeners rode away, never to be seen again. A local man found Gleason and Marshal Bashore. The dying marshal identified his killers (and Gleason as an assailant), and he said bushwhackers (who “had sworn resistance to the draft”) had come directly from the drilling site.

Provost Marshal Mathews suspected the murders were planned and that all Democratic Rangers were accessories to the crime. He called up militias from Grinnell and Montezuma and asked Governor Stone for help. Mathews set up roadblocks into Grinnell, and he sent militiamen to capture the Fleeners, Gleason, and the draft-deserters.

Three days later, Governor Stone arrived, passing out new Springfield rifles to the militiamen, who rode off to arrest the remaining Democratic Rangers. Grinnell militiamen bagged six Colt revolvers, a pistol, a horse pistol, 15 rifles, eight shotguns, and ammunition. They also arrested 16 men.

The editor of the Burlington Weekly Hawk-Eye, a Republican paper, assumed the worst. He wrote, “The Unionists of Poweshiek are naturally a good deal stirred up, and if the long-threatened Copperhead war is now to begin, they are ready.” He also demonized leading Democrats as being “armed and ready, with murder in their hearts … but waiting the opportunity to deluge the country in blood. Our safety is in their cowardice and want of opportunity.”

The Montezuma Republican editor made political hay, calling Poweshiek County Democratic leaders “more guilty in the sight of God, and more deserving of punishment, than the three men who committed the murder[s].”

The evidence suggests that the Fleeners murdered the marshals to keep their uncle Joseph Robertson from being impressed into the U.S. Army. Gleason, on the other hand, was a Democratic Ranger who expressed drunken bravado (about the marshals) to the Fleeners. He unwittingly stepped into a nightmare that spun out of control. The Democratic Rangers as a group just happened to be drilling the day of the murders.

Authorities in 1867 released every Democratic Ranger except Michael Gleason, who was tried and sentenced to death by hanging. President Andrew Johnson commuted his sentence to life in prison, where Gleason died in 1875. The Fleeners escaped justice.

Tempers and emotions had dissipated by 1911, and Sugar Creek Township’s odious Copperhead reputation faded. Poweshiek County historian Leonard F. Parker wrote that the former Democratic Rangers “were evidently misled. We are glad to accord them an honorable place among good citizens since that unfortunate hour in 1864 … The war is over. Neighborly relations have been restored.”

David Connon has studied pre-war and war-time Iowa for the past 15 years. A bleary-eyed veteran researcher, he has found that primary sources sometimes lead to rich stories. He has documented 76 Iowa residents who left that state and served the Confederacy. He shares some of their stories on a blog, Confederates from Iowa: Not to Defend, but to Understand. The blog also delves into the Iowa Underground Railroad, the Iowa home-front, war-time violations of civil liberties, and book reviews. He speaks to audiences across the state through the Humanities Iowa Speakers Bureau, and he works as a historical interpreter at Living History Farms. He has a master’s degree in Education from Northern Illinois University.

Very good article…

Hi, Ed. Thank you for your kind comment.

Hi David….I am particularly interested in accounts of Iowa in the Civil War. I have been researching and writing about Thomas Drummond, a newspaper editor in Vinton, Iowa and later a Union officer. He is buried in his home town, St. Clairsville, Ohio, which is also my home town. Your article is very good….

Hi, Ed. Thank you for your kind feedback. If you’re interested in reading more about the political tensions in Iowa during the war, I would recommend Civil War Iowa and the Copperhead Movement by Hubert H. Wubben.

Mr. Cannon,

I just enjoyed your article while looking for Poweshiek County (where I grew up), plat maps. There may be something about living in the Skunk River Valley as my family originally settled (1850’s) near Granville, North of Peoria & West of Taintor. I commuted to Vermer Mfg with a probable decendent of Cyphert Talley and showed livestock at the Poweshiek County Fair with some Fleener boys in the ’70s so I can attest to the orneriness of the family lines.

I now live in the English River Valley and there may be something in our water, too. I’m sure the English Valleys History Center would enjoy hearing your stories although I confess I have not attended since COVID began so if you’ve come and gone, I’m sorry I missed you. No need to reply, I’m just putting in to words what some generalized thumbs-up emoji implies, hoping I did it better. D. Fleming

Excellent account of a sad incident.

Thank you, Dennis. I was fortunate to find many pertinent documents in the Poweshiek County Historical Society, the Grinnell College Archives, and the State Historical Society of Iowa Archives in Des Moines.

David, as always, your research is insightful and well documented. I often wonder if the reason Grinnell’s house no longer exists could be from simply wanting to erase the past so people could go forward. Usually a historical player of Grinnell’s stature and wealth manage to stay in the public eye long after they have died with the preservation of their artifacts, often including the house they lived in. Grinnell’s connection to the UGRR and John Brown are well known, but his house is no longer a land mark of those times nor is it present to remind people of the unfortunate incidents that happened in the county. Keep your research coming, David, I enjoy seeing someone expose their love of history and the lessons we all need to be reminded of to keep us from repeating the mistakes of the past. Well done!

Hi, Steve. Thank you for your kind comments and encouragement. You make some good points. I imagine that on the day J.B. Grinnell’s house was torn down in the early 1960s, a few historians cried.

Thanks for documenting this important “local” history. The war was context for many interesting stories close to home. This one reminds me of the incidents dramatized in the movie “Cold Water Mountain”.

Hi, George. Thank you for an intriguing comment.

As a son of Iowa (Council Bluffs), great to see an Iowa Civil War story. Thanks.

Thank you, Dwight. Iowa was a very interesting state during the Civil War.

Excellent article. Thanks to your work, I am constantly finding out how little I know about the CW time frame.

Thank you, Raian. The Civil War is certainly a huge field!

Joe Fleener went on to be a reputable citizen of Missouri and later on became a Director of a Bank.

John totally disappeared although he was reported to be in various places in the Midwest.

Very interesting article. My family is from that area and I think I have figured out where the incident took place. It’s about 2 miles from the acreage we still own. My own 3rd great grandfather and my 2nd great grandfather’s brother were arrested after the fact but soon released. There was another murder a year earlier that may have been related that I’m looking into now. The Little Mount Baptist Church that my 3rd Great Grandfather helped charter in 1854 was also burnt down during this time because it was thought the Democratic Rangers were using it as a meeting place. So much information scattered around, it’s great to see it in one concise format. Thanks