Wah-Who-Eeee! … And The War Came to the Rebels, Part 2

Author Margaret Mitchel wrote her version of the sound of the rebel yell as “Wah-Who-Eeee,” and that was the sound heard throughout the Southern states when Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard opened his well-prepared cannon on shabby little Fort Sumter. The cannonade began at 2:30 am on April 12, 1861. Surprised by Major Robert Anderson’s move of his garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, the Confederate movers and shakers were in no mood with which to be trifled.

South Carolina had already set the high bar for secession on December 20, 1860, and by April of ’61, six more states had joined her in their protest movement against a Lincoln presidency. Repeated attempts by the Federal government to supply the small Union garrison only provoked the Confederacy into more tension. Talks between the two sides fell apart rapidly. Finally, Beauregard loosed his cannons, and the war was on.

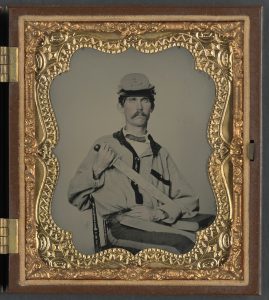

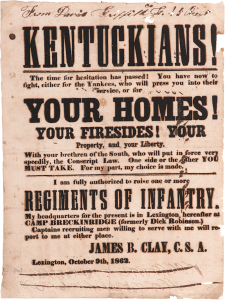

As early as 1858 (some say earlier) southern politicians had explicitly been planning for the creation of a country of their own. Not knowing what sort of resistance they might face, men in the south had already created local militia groups. Sporting hand-made secession cockades and a variety of uniforms, local fellows gathered in bars and barns to discuss the upcoming war efforts. Becoming a soldier was the prerogative of white men only. Excluding old men and young boys meant that the men available for Confederate service numbered just under two million, but that was not an issue. After all, one Southron could beat five Yankees–no problem.

Confederate president Jefferson Davis made no parallel call for volunteers, but that did not stop eager men from banding together. There were few cities in the seceded states whose population came anywhere close to those in the North. Instead, men not already in militia groups rushed to join the local unit or formed one of their own. These rarely met the standard number for qualifying as a company much less a regiment, but enthusiasm tried to make up for shortfalls. They named themselves for their state, for the man who had contributed the most money to raise the unit, or for an agreed-upon emblem of war. Some examples are Marmaduke’s 18th Arkansas Infantry, the Black Horse Cavalry, the President’s Guard, the Louisiana Tigers, and Poague’s Battalion-Artillery.

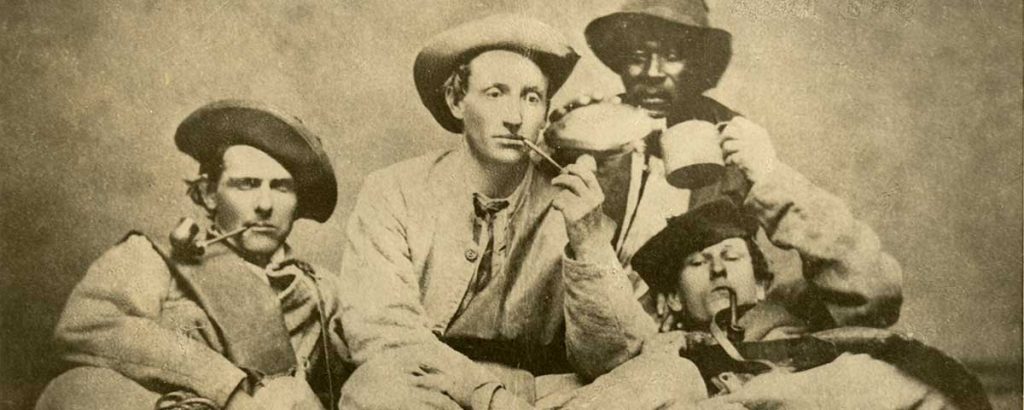

The southerners may have been less martial in appearance than Union volunteers, but the homespun of their uniforms, the carrying of a family weapon, or the riding of a family horse gave them an elån such as no army had demonstrated before. Each small group of friends rode wagons, horses or trains toward the newly-declared capital city of Richmond, Virginia. This early in the conflict many of the young men were of the best southern families. Family slaves into whose hands their mistresses had entrusted the lives of “young marster,” accompanied many. Others arrived with brothers, cousins, uncles and lifetime friends, all vowing to take care of each other.

Just as young men from the North committed their thoughts to paper, so did young men from the South. Excited about the possibility of a war, young A. J. Osborne of North Carolina shared some of the excitement with his brother:

Wednesday morning about 11 o clock, and found all as well as usual. I know of nothing particular to write you, except about the general excitement that prevails over here. I was over at Waynesville on Saturday last, Capt Robert Love made up a company of volunteers off a about a one hundred in number, & Samuel Bryson made up a company of about 25 or 26 of volunteers of footmen. The light horse company consists of 50 in number Mr. T.J. Lenoir is going to get up on Pigeon River. Write soon. excuse my scribbling & Blotching this I had to write in a hury. No time to take pains. give my love to all. your affectionate Brother A.J. Osborne [1]

Mississippi newlywed William Nugent wrote to his wife Nellie a month after the Battle of First Bull Run:

My dear Wife…I feel that I would like to shoot a Yankee, and yet I know that this would not be in harmony with the Spirit of Christianity….The North will yet suffer for this fratricidal war she has forced upon us—Her fields will be desolated, her cities laid waste and the treasures of her citizens dissipated in the vain attempt to subjugate a free people.[2]

According to North Carolina volunteer Bill Osborn the food was terrible in camp, and illness rampant. Bill wrote this letter to his brother David in October, 1861:

I will say to you it goes prety hard with me to live without eating, to eat what we do get is not fit to eat and only half rashions at that, you know that I have all ways had that which was good and plenty Oct 26th 1861 Since I wrote the last Page there has bin two of our men cared off to the Hospittle with Tyfoid fiver Mr James A Blalock and Tillman Bug. the last named is very low. I think uncertain whether he recovrs or not. J.A Blalock is one of my mess and is very clever young man if we should lose him I should reget it very much. I hope our kind Protection will return him to health a gain. Our Dr says that there is gowing to a greadeal of fever heir for the last month I have not Bin able to Drill my self But I now Beter than I have Bin I Pray God that he may restore my Father, that I many return to my friends. [3]

The Army of the Confederate States of America created itself out of whole cloth. Its military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and won appointment to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Some had experience in the Mexican War, including Davis and Robert E. Lee, but many had little or no military background at all. The officer corps, like the men under their command, was composed of both slave-holding and non-slave holding members. Election from the enlisted ranks provided Confederate junior and field grade officers.

The Army of the Confederate States of America created itself out of whole cloth. Its military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and won appointment to senior positions in the Confederate armed forces. Some had experience in the Mexican War, including Davis and Robert E. Lee, but many had little or no military background at all. The officer corps, like the men under their command, was composed of both slave-holding and non-slave holding members. Election from the enlisted ranks provided Confederate junior and field grade officers.

As in the North, war fever was high. Proud parents sent their sons off to war, and loving hearts made promises. Drums rattled, bugles brayed, and southern poets wrote words of encouragement and victory. Such was 1861. Henry Timrod, poet-laureate of the Confederacy, wrote as patriotically as Walt Whitman.

A Cry to Arms!

Ho! woodsmen of the mountain side!

Ho! dwellers in the vales!

Ho! ye who by the chafing tide

Have roughened in the gales!

Leave barn and byre, leave kin and cot,

Lay by the bloodless spade;

Let desk, and case, and counter rot,

And burn your books of trade.

The despot roves your fairest lands;

And till he flies or fears,

Your fields must grow but arm|\ed bands,

Your sheaves be sheaves of spears!

Give up to mildew and to rust

The useless tools of gain;

And feed your country’s sacred dust

With floods of crimson rain!

Come, with the weapons at your call —

With musket, pike, or knife;

He wields the deadliest blade of all

Who lightest holds his life.

The arm that drives its unbought blows

With all a patriot’s scorn,

Might brain a tyrant with a rose,

Or stab him with a thorn.

Does any falter? let him turn

To some brave maiden’s eyes,

And catch the holy fires that burn

In those sublunar skies.

Oh! could you like your women feel,

And in their spirit march,

A day might see your lines of steel

Beneath the victor’s arch.

What hope, O God! would not grow warm

When thoughts like these give cheer?

The Lily calmly braves the storm,

And shall the Palm-tree fear?

No! rather let its branches court

The rack that sweeps the plain;

And from the Lily’s regal port

Learn how to breast the strain!

Ho! woodsmen of the mountain side!

Ho! dwellers in the vales!

Ho! ye who by the roaring tide

Have roughened in the gales!

Come! flocking gayly to the fight,

From forest, hill, and lake;

We battle for our Country’s right,

And for the Lily’s sake!

Henry Timrod[4]

_________________________________________________

[1]http://wcudigitalcollection.cdmhost.com/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16232coll5/id/100/rec/1

[2]https://www.historynet.com/darling-nellie-southern-soldiers-letters-home.htm

[3]http://wcudigitalcollection.cdmhost.com/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16232coll5/id/110/rec/4

[4]https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/a-cry-to-arms/

Meg

One of the bug-bears of early operations during the Civil War: “What time is it?” In 1861 there was no Standard Time, no daylight savings; clocks across America were set by Meridian Passage, i.e. High Noon. A clock in town would be properly set, and individuals would adjust their personal timepieces to the hour recorded on that clock… and then allow their watches to run, often several days, before being adjusted once more. Meanwhile, slow-running watches could accrue fifteen minutes or more disparity with fast-running watches (as occurred Battle of Shiloh). The first recorded use of “synchronized watches” was by U.S. Grant’s Corps Commanders during the Vicksburg Campaign of 1863.

At Charleston, South Carolina on the morning of 12 April 1861 Mary Chesnut recorded “hearing St. Michael’s chimes at 4 am …and the first gun opened up half an hour later.” Her husband, James, was suspected to be in a small boat with Stephen D. Lee on Charleston Harbor, returning from Fort Sumter, having delivered a communication from Brigadier General Beauregard at 3:20 am, informing Major Anderson that, “the bombardment will begin in one hour” [OR 1 page 14.]

I always think of this when accounts state that someone or some army was on the march by 4 AM. So—maybe 7 AM pacific time?? ( joke)

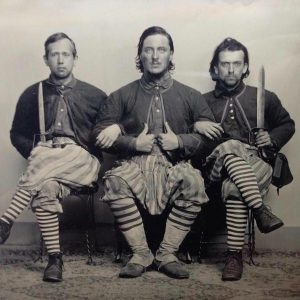

A good article! Worth pointing out briefly that the photo of Wheat’s Tigers is actually a modern photo taken of reenactors. Very good reenactors, but reenactors all the same.

Alas, the real Wheat’s Tigers seem absent from the image category. I thought these guys looked pretty good, but admit that I sent the blog post before I rechecked the captions. Whew! Thanks!!