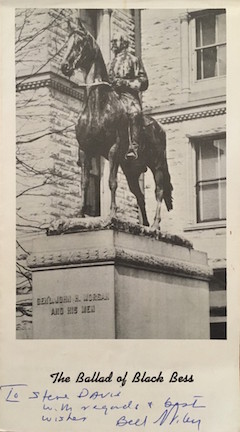

The Ballad of Black Bess

[Editor’s Note: With all that’s happening about Confederate monuments these days, it’s all right to remember a time when monuments to Confederate heroes became a source of humor.]

[Editor’s Note: With all that’s happening about Confederate monuments these days, it’s all right to remember a time when monuments to Confederate heroes became a source of humor.]

Robert E. Lee had Traveller and Stonewall Jackson his Little Sorrel. Bedford Forrest rode King Philip, and that other famed Confederate cavalryman, John Hunt Morgan, had Black Bess.

When I was in college at Emory, the late great Professor Bell Wiley gave me a leaflet, “The Ballad of Black Bess,” which the director of the University of Kentucky Press had given him.

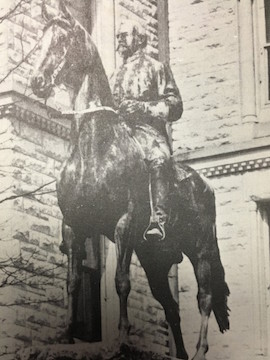

In 1911, on the courthouse lawn in Lexington, Kentucky, was dedicated a fine equestrian monument to General Morgan, nobly mounted on Black Bess. The Yankees captured her at one point, and we don’t know what happened to her.

But we know that she was a mare.

The sculptor of the Lexington monument thought it unbecoming, however, that General Morgan should be depicted as riding a mare—something more manful was in order.

The sculptor of the Lexington monument thought it unbecoming, however, that General Morgan should be depicted as riding a mare—something more manful was in order.

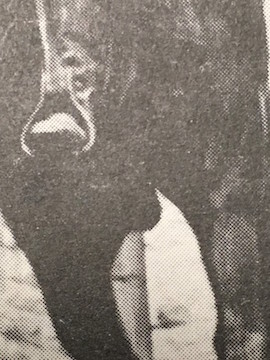

So he physically fashioned Black Bess from mare to male.

Here’s the poem contained in the flyer that Dr. Wiley gave me (author unknown).

The Ballad of Black Bess

Though art and science oft collide

Let art make no apology,

For here is proof that art can win

O’er more mundane biology.

A sculptor came to cast the fame

In metal’s mold eternal.

Of Morgan and his faithful mare

And their bold deeds supernal.

The sages of the Bluegrass gave

Advice with clear simplicity.

Their chiefest hero must appear

With faultless authenticity.

And pride flashed in the sculptor’s eye

When told of Morgan’s prowess,

How oft the conquered the field

On his good mare Black Bess.

But a Jovian frown now dark’d his brow

As the artist heard this last.

“No hero should bestride a mare!”

Said he, “I am aghast!”

The graybeards showed him that ‘twas true,

From Sumter to the Wilderness,

Morgan’s fame was won, his deeds were done

On none other than the mare Black Bess.

The artist’s mood regained its calm

As was anticipated.

At last there come the festal day

For which the Bluegrass awaited.

Now is unveiled the statue’s face.

The throng’s in joyous strife.

“Praxiteles this sculptor is!

It’s Morgan to the life!”

The bunting parts now to display

The head of good Black Bess.

The faithful likeness moves the crowd

To cries of happiness.

At last the bunting falls away

And all now stands revealed.

A gasp of horror sweeps the crowd

At what had been concealed.

For down the corridors of Time

And up to Heaven’s vestibules,

Morgan fore’er will ride a mare

Equipped with a pair of testicules.

No shadows on the General’s face;

His brow remains serene.

No mark of this great travesty

Is apparent from his mien.

And proud the eye of good Black Bess

With shamelessness uncanny,

She just ignores the testicules

That hang beneath her fanny.

The truth is all our homage due

But scholars must confess,

That art o’er fact hath won the day

With the balls of good Black Bess.

What saddens every Bluegrass heart

Is a continuing tradition,

For students in their annual pranks

To alter Bess’s condition.

Now every year the faithful mare

Must suffer violation.

Her balls are painted every hue

Known to imagination.

So sorrow comes to Bluegrass men—

Like darkness o’er them falls—

For well they know gentlemen should show,

Respect for a lady’s balls.

Well, as a transgendered statue here at least is one ancient monument that should remain immune from the modern wrecking ball of sensitive opinion.

I thought Lexington removed the statue? Out of sight out; out of mind and eventually gone from our collective history.

It’s in Lexington Cemetery. I visited it just last week. I’ll have a picture to share in a couple days.

My great grandfather rode with Morgan (Wm Elam); my collateral great uncle (Dr. Gorham) paid $5,000 for bond from Columbus, Ohio prison. Morgan and Wolfe Counties heritages. Desperate times.

A fact seldom mentioned is that Morgan lost Black Bess at the Battle of Stones River in December 1862, according to his biographer, James A. Ramage: “There was no time to save her, and Morgan would never see her again.” So he rode other horses in 1864 up to his death that September. Could they have been stallions?

Stealth was important to Morgan’s success at spying out Yankee movements – and Stallions were boisterous and noisy. (I don’t know about Geldings.) Mares were quieter, more suited for Morgan’s intel gathering. So I have read.