Acts of violence against America

Acts of violence against America.

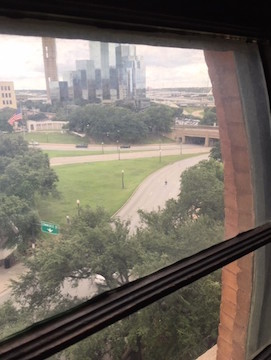

That’s the context an exhibit panel challenged me to consider as I neared the end of the self-guided tour of the Sixth Floor Museum in the Texas Book Depository overlooking Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas. The site had, for decades, been near the top of my bucket list of places I wanted to visit.

Later in the day, I planned to visit another destination on that list: the site of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. My interest in that tragedy sprang from the work of Daniel Herbeck and Lou Michel, reporters from the Buffalo News who wrote the first in-depth book about the bombing, American Terrorist. Dan is an alum of St. Bonaventure University, where I teach. Through excellent reporting, the two reporters earned exclusive access to the bomber, Timothy McVeigh, who was from the Buffalo suburbs. Dan and Lou’s thorough and thoughtful work years ago inspired me to someday visit the memorial.

Yet there in the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, I suddenly and unexpectedly found Dealey Plaza and the Oklahoma City Federal Building tied together in a single exhibit.

The exhibit placed both JFK’s assassination and the Oklahoma City bombing in a line of events that began with the attack on Pearl Harbor, complete with a photo from the attack as well as a photo of JFK visiting the U.S.S. Arizona memorial years later. The exhibit panel also tied in the attacks of 9/11. One should credibly add the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center to that list, too.

And, certainly, if JFK’s assassination merits inclusion as an act of violence against America—as it absolutely does—so too do the slayings of presidents McKinley, Garfield, and Lincoln. We can thread together a narrative from 9/11 all the way back to Ford’s Theatre.

And from that tragic moment at the tale end of the Civil War, isn’t it just a chronological skip back to the eve of war, when John Brown’s men attacked the Federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in an attempt to trigger a slave uprising? Was Brown a freedom fighter or domestic terrorist?

This unexpected exhibit in Dallas gave me much to ponder during the rest of the day, and it made me all the more eager to get to Oklahoma City. Rather than make the straight shot northward on I-35, though, I intended to make a side trip to Fort Towson, Oklahoma, and the nearby Doaksville archeological site, both situated in the state’s southeast corner. In Doaksville, on June 23, 1865, Stand Watie surrendered the last Confederate forces of the Civil War. This is yet another site I’ve long wanted to see for myself.

By the time I eventually got to Oklahoma City, it was 10:30 at night—but that’s arguably the best time to see the memorial because of its striking lighting and somber atmosphere. It’s simultaneously beautiful and haunting. The noise of the city has quieted, and stillness pervades.

A reflecting pool, like a smooth plane of obsidian, runs between two black walls. One says 9:01; the other, 9:03. In the moment in between, represented by the still, flat, dark surface of the water, everything changed. Oklahoma City changed, but so too did America, forever. Terrorism struck home. Domestic terrorism.

One-hundred and sixty-eight vacant chairs—explicitly reminiscent of H. S. Washburn’s Civil War-era poem of that name—sit on a hillside where the Murrah Federal Building once stood. “The Field of Empty Chairs,” as it’s called, is arranged in nine rows, one row for each floor of the building, one chair for every victim; nineteen small chairs represent the children from the building’s daycare killed in the blast. Symbolism is built into the entire memorial.

The experience overwhelmed me. At first, I tried to capture a sense of that impact on video (posted later to ECW’s YouTube page). I quickly realized the experience was beyond words—a particularly impotent feeling for a writer—and I fell into choked silence. I sat on a bench facing the reflecting pool, facing the chairs, and began to weep.

My own stillness returned only slowly. As it did, I thought about this American atrocity and how it compared to the other acts of violence against America I had contemplated earlier in the day.

As I thought of that series of events—from 9/11 backwards all the way to Ford’s Theater and Harpers Ferry—I saw my trip to Doaksville that day in a new light.

I had considered Doaksville an aside to the day’s larger theme, unrelated to the events strung together by the exhibit in the Sixth Floor Museum. But standing beside the reflecting pool at the Oklahoma City bombing memorial, I suddenly saw the Doaksville trip—indeed, the entire Civil War—as part of the continuum suggested by the museum display.

Was not the Civil War itself an act of violence against America?

“[T]he South had rebelled against the National government,” Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his memoir, framing in no uncertain terms what the war meant. Jefferson Davis, personifying the Confederacy, “lent all his talent and all his energies to destroy” the United States, Grant wrote elsewhere in his book. “He represented all there was of that hostility to the government which had cause four years of the bloodiest war….”

Because of that hostility, the Federal government had an obligation to defend itself. “While [the Constitution] did not authorize rebellion it made no provision against it,” Grant conceded. “Yet the right to resist or suppress rebellion is as inherent as the right of self-defense….”

I balance Grant’s thoughts about rebellion against Thomas Jefferson’s now-famous exhortation. “what country before ever existed a century & half without a rebellion?” he wrote in 1787 to William Stephens Smith. “& what country can preserve its liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? let them take arms…. the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots & tyrants. it is it’s natural manure.”

Jefferson’s words are sometimes taken as holy writ by ardent Lost Cause advocates and many on today’s alt-right. In the context of this series of infamies from 9/11 back to Ford’s Theatre, Jefferson’s sentiments ring with hollow States Rights excusism. He was also but one man expressing his personal opinion in private correspondence, and he had no greater authority than any other Founder (and less than many because he had no influence on the Constitution itself).

Jefferson, who saw no combat during the Revolution beyond his near-capture by British forces when he was governor of Virginia, seems almost flip when he asks Smith, “what signify a few lives lost in a century or two?”

I might ask him to pose that question to the 620,000-750,000 people who lost their lives during the Civil War.

I visited Dealey Plaza, Doaksville, and Oklahoma City on a pleasant day in early June. It could not have been a more perfect day for exploring. I knew it would take me some time, though, to get my head around everything I experienced that day. And now here I sit, on the eve of 9/11, finally trying to put some of those thoughts into words. The anniversary gives me a fresh opportunity to again reflect.

The attacks in New York, D.C., and Shanksville, PA, remain fresh. We can all remember where we were when we heard the news and when we saw the towers fall. Many of us knew people affected by the disaster; others knew people who knew people.

Many remember exactly where they were when they heard news of Kennedy’s assassination.

Some are still with us who even still remember where they were when they heard news of Pearl Harbor. President FDR called it a “day of infamy.”

Aren’t all these events days of infamy—and the Civil War, an act of violence against ourselves and each other, the most infamous of them all?

I’m also reminded that my freshmen this year weren’t even alive when 9/11 happened. For all my students—freshmen and upperclassmen—9/11 is history rather than something they lived through. Do they have a perspective on this ignoble chain of events that those of us, with our lived experience, cannot have? Is the answer even knowable?

As a nation, we are engaged in mighty discussions these days about what it means to be an American. Our politics, some say, are as divided as they were on the eve of the Civil War.

I pray it does not take some great act of violence against America to bring us back together.

Excellent! Meaningful! Timely! Thank you Chris!

Thanks, Andy!

Excellent, insightful post.

Thanks, Brian!

A wonderful post, particularly on this day. The 19 small chairs at the OKC memorial is particularly poignant; I hope to go there some day.

I echo, great post. You know, in times of duress and challenge and threat, Americans will and do come together. But, the ability to ‘return to normal’ is an inherent strength as well, even in those times of duress and loss and mourning. Many of the same partisan political arguments and maneuverings that took place during the Civil War and the World Wars and all the others continue now. The Civil War, to the best of my knowledge, is the last conflict that resulted in a fundamental, and permanent, change in the way of life for large segments of the population. Yet through it all one can always ‘count’ on the usual kinds of political discourse. I don’t always like what goes on, but I DO accept it all as ‘business as usual’, and I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

That said, God bless all the victims and their loved ones of these atrocities, past and future, as we know there will be more. I personally view the mass shootings and other such incidents as attacks on the country, in that they attack the NORMALCY that we expect within our society. When kids are targeted in places like schools, it cuts deep into our collective psyche and shocks us beyond the litany of other events that we sometimes grow numb to. And that’s the idea, to shock us as a collective. Oklahoma City was horrible, but the image of that dead baby being carried by the fireman remains particularly haunting. Never forget, and strive to prevent such things as best we can…

Memorials built to remenber built to reflect built to learn built for tribute built not and i pray not to some day be thrown down by a future generations thinking of only of themselves.

The memorial for the Murrah Bldg victims hits me the hardest. I was in OKC when the bombing happened. We were 7 miles away, but we heard and felt it. The info on the radio and TV was spotty. And the roads out of OKC were closed.

You forgot to mention John Brown’s Raid. That was an act of violence against America.

And should have added the Marais des Cygnes Massacre. That, too, was an act of violence against America.

Definitely. Why not throw in Pottawatomie as well?