Playing the numbers: Robert E. Lee, the Army of Northern Virginia, and Maryland in 1862

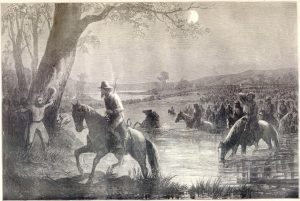

The Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River into Maryland on September 4, 1862, embarking on what history has come to call The Antietam (or Sharpsburg) Campaign. In three months, since Lee took command outside Richmond, he had won a succession of battlefield victories and transferred the war from the doorstep of the Confederate Capital to Union Soil. It is a well-known story.

Then, of course, came the battle at Antietam Creek. Lee, outnumbered two to one (as the common wisdom has it) faced down Union General George B. McClellan and forced at least a draw on America’s bloodiest day, September 17, 1862.

Only Lee could win against such odds. Only McClellan could lose. Or so says the conventional wisdom. McClellan reported “87,164” officers and men engaged in the Army of the Potomac, while Lee’s numbers, less well articulated, numbered around 40,000.

In fact, the numbers have become controversial. Southern veterans, in an effort to burnish Lee, continually downplayed Confederate strength in the post-war era. Given the lack of official returns for that period, they had ample room to maneuver. Even Northern veterans largely accepted the lower figures. As a result, estimates range from as low as 35,000 to upwards of 50,000 Rebels fighting at Antietam. Ezra Carman, in his monumentally authoritative manuscript of the campaign, cites Lee has having 37,351 troops engaged – among the lowest of those estimates. Of course, Carman also reduces McCLellan’s numbers from the 87,164 present for duty reported by the Federal commander to 51,636 Union troops actually engaged, plus another 4,320 Yankee cavalry. Carman eschewed to count all the Federal troops present but not committed, which, arguably, plays fast and loose with history.

The numbers game is well-known, and I won’t rehash it here.

Instead, what interests me is: what happened to Lee’s army?

It is a much less well-known fact that we do have pretty good numbers for Lee’s strength on September 2, 1862, two days before he crossed into Maryland. Those numbers are surprising, even shocking.

Lee had just fought the battle of Second Manassas, where he won a victory over John Pope, but suffered heavily in the process. He made up for those casualties, however, with reinforcements brought up from Richmond, under D. H. Hill. Thus, on September 2nd, Robert E. Lee’s present-for-duty strength numbered no less than 75,528 officers and men – far larger than the force he led into action just fifteen days later.

Headquarters – 6

Longstreet’s command – 19,628

Anderson’s Division – 5,712

Jackson’s Command – 20,612

Stuart’s Cavalry – 5,664

Reinforcing column

McLaws’ Division – 7,652

D. H. Hill’s Division – 9,794

Walker’s Division – 5,159

Reserve Artillery – 1,299

total: 75,528

The source for these numbers is an obscure but highly important unpublished thesis:

John Owen Allen, The Strengths of the Union and Confederate Forces at Second Manassas, Master’s Thesis, George Mason University, 1993.

To arrive at his numbers, Owen delved deeply into the Confederate Company Muster Rolls and Regimental Returns of RG 109, Captured Confederate records, in the National Archives. None of those records made it into the Official Records, but they do go a long way towards compensating for the relative lack of tri-monthly returns for the Army of Northern Virginia during this period.

These numbers suggest a couple of things:

First, that the much-maligned George B. McClellan was more correct than usually given credit for in estimating Lee’s strength. On September 8, McClellan reported that Lee had 110,000 men at Frederick. If in fact Lee had 75,000 men present for duty on September 2, his “aggregate present” number was considerably higher – at least 90,000 men, perhaps 100,000 – aggregate numbers were usually 20 to 25% higher than present for duty numbers, and 30% higher than what the Confederates typically reported as “effectives” (enlisted men only, ready to fight.) The aggregate figure – used by both sides – represented the total number of men with an army, not just those ready for combat, and the total number of mouths to feed. In terms of intelligence gathering, it would also be the most common basis for estimating enemy strength. After all, spies would be counting bodies and estimating sizes of formations. With a present for duty strength of 75,000, Lee’s aggregate would be around 94,000 men.

That alone is a pretty interesting conclusion, and one that upsets the conventional wisdom apple-cart where George B. McClellan is concerned.

But it also suggests that Robert E. Lee’s army was starting to unravel.

If the Antietam number estimates are accurate, at least one third of the Army of Northern Virginia’s combat strength melted away within a fortnight of September 2nd. If Carman’s 37,351 engaged number is correct, then no less than half of Lee’s army disappeared due to straggling and desertion within that two week period.

There have long been explanations addressing this decline in numbers: ranging from poor supplies and the ragged condition of the troops to southern reluctance to be perceived as “invaders” rather than defending their home soil. I think the first two reasons raise legitimate points, but the third stretches credulity: it smacks of post-justification rather than reality at the time. Some few men might have fallen out for that reason, but half the army? Really?

And to some extent, the losses of the Harper’s Ferry and South Mountain operations are buried within those numbers; not every one of those missing 25,000 men (at least) were stragglers.

But a better explanation is that Lee’s string of triumphs that summer came at a much higher price than previously supposed: The army was simply marched and fought into the ground by September.

Certainly no one can argue that the troops that captured Harper’s Ferry, defended South Mountain, or stood their ground at Antietam Creek had lost combat effectiveness. But the defections do raise the question: how much more active campaigning could the army stand? What if Lee had gone on into Pennsylvania that fall?

I first encountered these numbers in the late 1990s, in my previous incarnation as a designer of cardboard wargames. Any wargamer is deeply interested in numbers, and Antietam, as the number of games about that battle attest, is a deeply studied subject.

Surprisingly, aside from the late Dr. Joseph Harsh (who headed the History Department at George Mason when Owen produced his study) and the more recent To Antietam Creek by Scott Hartwig, few scholars have cited Owen’s work – which is a pity, given the number of important questions Owen’s numbers raise about the state of the Army of Northern Virginia as it crossed into Maryland.

Hard to believe Lee had at least 90,000 men, perhaps 100,000 – aggregate at Fredrick MD. This does not make sense at all. Much more research needs to be done on this subject. I think it is entirely possible Lee had 50,000 at Antietam but not much more if any.

John, Likely he didn’t have 90,000 men at Frederick. I don’t think he did. But then the question becomes: why? We know what he had _before_ crossing the Potomac. Was he down to 70,000 at Frederick? 60,000? My point is more about what was happening to the Army of Northern Virginia.

I too am a bit skeptical about the 90-100K number. It’s hard to believe, after the long summer of 1862, with almost continuous action featuring the Peninsula Campaign, the Valley Campaign, Second Bull Run, and quite a few smaller clashes, that the Confederates could field an army of that magnitude.

Would those ‘aggregate numbers’ apply to McClellan’s forces as well?

Given how Antietam happened after a full year of war, and that the Confederates in the East had enjoyed some considerable success, might the influx of volunteers have been high? Nobody that I am aware of has ever explained Pinkerton’s basis for determining that The Confederates had so many troops at the Seven Days, which (supposedly) influenced so many of McClellan’s actions and decisions. Did any militias and ‘home guards’ convert over to regular troops and join the AONV? Some interesting questions are raised by this.

That said, regardless of how many troops Lee had, having just SIX HQ staff seems quite minimal.

Douglas, certainly they would. And Mac was not above selectively using different “numbers” when it suited him. He certainly did so on the peninsula, comparing his effectives to Lee’s aggregate .

Fascinating discussion. I have noticed some of those discrepancies before, and recall seeing some studies in this direction (but not Owen’s, which offers great food for thought). The conclusion appears inescapable that Lee’s army partially melted away starting at the Potomac.

As a side note, I don’t recall seeing this same issue among Western armies at this time – certainly not Bragg and EK Smith’s forces in Kentucky. The Westerners had been moving far and fast since January 1862 through a generally fluid strategic situation. I wonder if the Army of Northern Virginia’s collective stamina had been weakened by the positional battles and relatively short maneuvers of the first seven months of 1862?

Agreed. I think the toll of suffering roughly 40,000 combat casualties between June 26 and September 2 took an immense toll on the army. Union losses weren’t much better, but they were spread across a considerably larger force pool, between the Army of the Potomac and Pope’s Army of Virginia.