Angel or Elf: Bronson Alcott and the Secret Six Plot to Assist John Brown

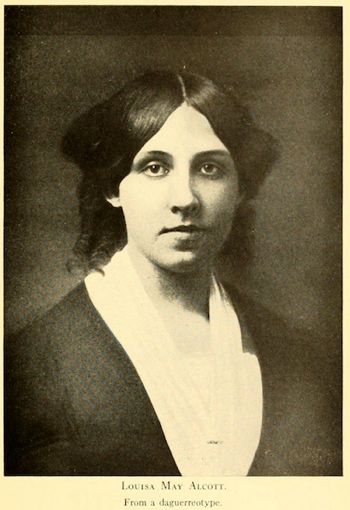

“Surely dear father, some good angel or elf dropped a talisman in your cradle that gave you force to walk thro life in quaint sunshine while others groped in the dark… “

–Louisa May Alcott to her father

November 28, 1855

Emerging Civil War has chosen to highlight the 160th anniversary of John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. To be sure that our work is complete, I would like to add a bit of information concerning the Secret Six and their assistance to Brown’s abolitionist work. As usual, nothing is as straightforward as it seems. Let us begin with fiction and see if we can tease some facts out of all this. There is a special “aha!” that comes to a young historian when she realizes that Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is actually a Civil War book. The male parent of the “little women” in the story is not at home. He is with the Army of the Potomac as a Transcendentalist chaplain. A little more investigation into Bronson Alcott–or Mr. Marsh, in Louisa May’s book–seems in order.

Bronson Alcott was, for years, only known as a minor light of the Concord, Massachusetts intellectual community that included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. He was a native New Englander born in Connecticut in 1799. He was homeschooled and self-educated, working outside his home from his early teen years. At seventeen, he passed an examination for a teaching certificate, but he had a difficult time keeping a job. He left home and became a traveling salesman whose territory was the American South. By 1823 he returned home, having to be bailed out of debt by his father.

Bronson began teaching again, but his enlightened ideas about public education made it difficult for him to retain his pupils. He moved to Boston in 1828, married in 1830, and began a friendship with abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. They founded an antislavery society together. Bronson Alcott continued to open schools that failed, even as his family kept growing. They usually found lodgings in Concord, Massachusetts, a small town to the north of Boston that was home to many great writers of the day. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau were neighbors to the Alcotts. They were an optimistic group who believed humans were capable of great thoughts, and they advocated nonconformity and being true to one’s inner self. Alcott was not a particularly responsible father or husband, although he was an enthusiastic transcendentalist philosopher, abolitionist, and teacher. He failed to provide enough money to support his family, and their poverty was so dire that in twenty years, they moved twenty times. Louisa’s mother acted as head of the household, and when second daughter Louisa grew older, she also took on much of the burden.

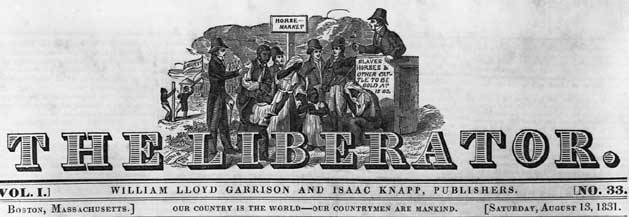

In Boston, William Lloyd Garrison’s publication of The Liberator added much to the already established antebellum abolitionist movement there. Garrison was an early supporter of John Brown’s efforts to incite a slave rebellion, and he influenced several men to consider putting money toward Brown’s efforts. They became known collectively as the “Secret Six,” although there were many more than six supporters. Bronson Alcott was one of them. Others included Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, and George Luther Stearns. All but Smith were active in the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts. Smith was a reformer and politician from New York state.[1]

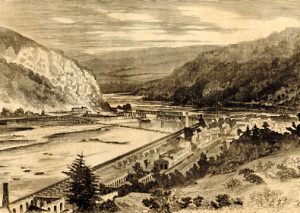

Before coming to New England seeking allies and financial support, Brown had moved with his sons to Kansas Territory. In response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas, he led a small band of men to Pottawatomie Creek on May 24, 1856. Brown and his sons dragged five unarmed men and boys, believed to be slavery proponents, from their homes and brutally murdered them. Afterward, Brown raided Missouri – freeing eleven slaves and killing the slave owner. Following the events in Kansas, Brown spent two and a half years traveling throughout New England, raising money to bring his antislavery war to the South–specifically to Harper’s Ferry.

Brown’s actions in Virginia and at the battle of Osawatomie, Kansas, were applauded by the antislavery populace in New England. Abolitionists and intellectuals, unaware of the bloody details of Brown’s operations at the Pottawatomie Massacre in Kansas, helped to establish the image of Brown as a martyr in the North. Members and supporters of the Secret Six, including Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, championed John Brown’s sacrifice while overlooking the violent aspects of Brown’s character. These influential writers and clerics promoted him as a heroic symbol for the abolitionist cause. Additionally, they put their money where their words were. Brown met with these men several times in 1858 and 1859, explaining to them that he wanted to attack the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. The purpose of the attack was to obtain weapons and ammunition, which would then be turned over to slaves in the area who would lead a slave rebellion in the South. Bronson Alcott, among others, handed over enough money to Brown to bankrupt his family for years.[2]

When Brown’s plan failed and he was arrested, the Sixers again reached into their bank accounts to fund Brown’s trial. Thomas Higginson even planned a jail escape, which never materialized. During this time, the New York Times and the New York Herald began to do a little investigative journalism. The newspapers started to tie the names of the men in Boston to Brown. None of these fellows were particularly skillful at managing public opinion, and panic ensued. Denying that he had been involved in supporting Brown, Gerrit Smith had himself confined to a mental hospital. Samuel Gridley Howe, Frank Sanborn, and George Luther Stearns fled to Canada. Theodore Parker was already in Italy for his tuberculosis, staying with Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. He elected not to return.[3]

When “John the Just,” as Louisa May Alcott called him, was hanged, this poem was published in The Liberator on January 20, 1860.

With A Rose That Bloomed on the Day of John Brown’s Martyrdom[4]

In the long silence of the night,

Nature’s benignant power

Woke aspirations for the light

Within the folded flower.

Its presence and the gracious day

Made summer in the room,

But woman’s eyes shed tender dew

On the little rose in bloom.

Then blossomed forth a grander flower,

In the wilderness of wrong,

Untouched by Slavery’s bitter frost,

A soul devout and strong.

God-watched, that century plant uprose,

Far shining through the gloom,

Filling a nation with the breath

Of a noble life in bloom.

A life so powerful in its truth,

A nature so complete;

It conquered ruler, judge, and priest,

And held them at its feet.

Death seemed proud to take a soul

So beautifully given,

And the gallows only proved to him

A stepping-stone to heaven.

Each cheerful word, each valiant act,

so simple, so sublime,

Speaks to us through the reverent hush

Which sanctified that time.

That moment when the brave old man

Went so serenely forth,

With footsteps whose unfaltering tread

Reechoed through the North.

The sword he wielded for the right

Turns to a victor’s palm;

His memory sounds forever more,

A spirit-stirring psalm.

No breath of shame can touch his shield,

Nor ages dim its shine;

Living, he made life beautiful,–

Dying, made death divine.

No monument of quarried stone,

No eloquence of speech,

Can grave the lessons on the land

His martyrdom will teach.

No eulogy like his own words,

With hero-spirit rife,

“I truly serve the cause I love,

By offering up my life.”

As a minor player in the plot to support John Brown, Bronson Alcott was not arrested. He continued to support causes in which he believed, such as women’s rights, progressive education, and even vegetarianism. Bronson Alcott died on March 4, 1888. His daughter Louisa followed him three days later. As a father, Alcott failed at much. Still, he and his wife gave his daughters an unwavering sense of morality and kindness. This inner system of belief propelled them to champion progressive causes and, in some cases, break laws that they deemed discriminatory.

___________________________________________

[1] https://www.masshist.org/features/boston-abolitionists/john-brown

[2] Edward Renehen, The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown. New York City: Crown Publishers, 1997.

[3] Ibid

[4] https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/rose-70

Meg, over the years I have compiled the following list of names connected with John Brown:

Thompson, Brown, Douglass, Beecher, Shaw, Green, Stowe, Sumner, Kagi, Lane, Hazlett, Cook, Andrews, Higginson, Stearns, Howe, Parker, Smith, Sanborn, Stevens, Coppoc, Thoreau, Tubman, Seward, Anderson, Newby, Copeland, Leary, Delany, Watson, Goodrich, Forbes, Emerson, Leeman, Meriam, Taylor, Tidd, Jim, Ben.

Thanks for adding Alcott to the list.

[Another excellent source: http://abolitionist-john-brown.blogspot.com/

I knew most of these. I think Harriet Tubman is going to be getting a lot more notice with the movie coming out. Seems like she had a finger in every pie back then.

Co-conspirators to murder and butchery. Trying to make a hero of a terrorist is rather unbecoming of you people

It has always puzzled me: “Why was the William Maxson house torn down?”

Now I know…

https://www.loc.gov/resource/hhh.ia0048.photos?st=gallery

No disagreement there. Brown’s actions were ill-thought-out, to say the least. I think the “Secret Six” is interesting, however. There were some pretty clumsy espionage attempts on both sides.

Speaking of “unbecoming”, we’re still waiting for that date when slavery was going to die a “natural death”. Crickets …..

The Harriet Tubman movie has potential to be EPIC, if correctly done…

Meanwhile, for everyone else (because Meg knows the answer): “Why are not the names of William Lloyd Garrison and Abraham Lincoln on the above list of John Brown supporters?”

Fascinating, Meg. I had no idea of the Alcott connection to John Brown. Thank you!

I agree. The idea that the father of a “children’s book” should be such a revolutionary is astounding to me. Ms. Alcott herself was pretty radical as well. I love all these folks–America has a wonderful history, and Americans have always lived in “interesting times.”

“Interesting times” indeed. That’s one of my favorite aspects of ECW, the focus on the unknown or little known aspects of the war… once one starts to dig, its remarkable what one finds. I was at the U.S. Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State not too long ago going through papers re Frederick Dent Grant and found very interesting the role he played in the post-war reconciliation effort. I was a bit surprised, however, to learn that in doing so he took some positions that did not align with those of his Father… in the larger interest of reconciliation. Anyway, I’ve been to the Alcott home in Concord and never heard about the John Brown connection. Really interesting. Thanks again!

This is a thoroughly fascinating period to me, and luckily ECW lets me write about “stuff.” Keep reading!

You have some very good information here, but I do think you’re passing off opinion as fact

when you say that Alcott wasn’t a good husband or father. I haven’t read any contemporary say anything to that effect about him, and definitely not his family. We don’t know if they thought it, but I wouldn’t call it academic to say anything of the kind unless his family indicated it. They were poor, and their life was unstable because of it, but he was a visionary, and his family gave every impression that they were behind him 100 percent. You may be right, but I wouldn’t say that given what we know.