Just Who Was Abraham? (pt. 2)

Before the war, there was an enslaved man called Abraham. His last name was unknown. Here is what is known: The black man known as Abraham was between 18-25 years old at the time of the Siege of Vicksburg. He was approximately 5’ 6” tall.[1] From all accounts, including Abraham’s own, he worked within Confederate Vicksburg. The Confederate Army often leased groups of slaves from local landowners to do the hard labor of war. Slaves dug ditches, entrenchments, latrines, graves, and apparently mines. It takes strength to do this, but not necessarily a particular skill, so these groups of enslaved men were considered simple laborers.

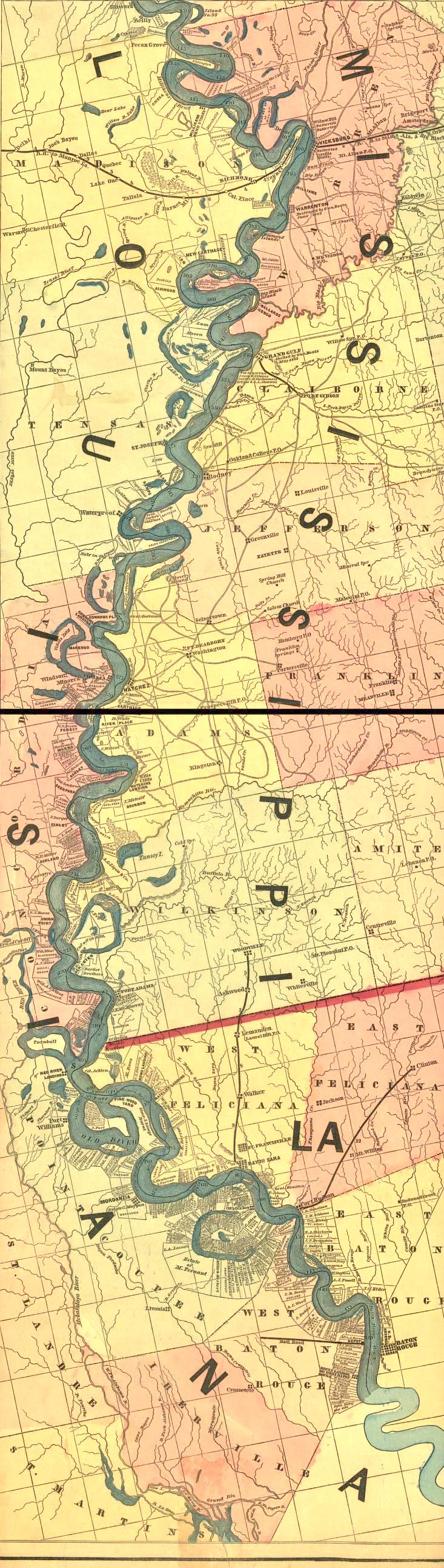

A look around the Vicksburg area narrowed down the landowners. Mike checked property lists and found no slaves simply named “Abraham” or “Abraham Landowner’s Name”. No Abraham Young, Abraham Harris, or Abraham Marshall. There were few enslaved men with the name of Abraham, which was surprising—unless they changed their names due to Lincoln’s election.

Abraham was not a laborer–he worked with food in some capacity. On the day of the explosion he was taking food to a team of men working below ground. These men were laboring inside the seriously damaged 3rd Louisiana Redan, known as Fort Hill by Federal forces. The Redan had been partially collapsed by the explosion of a mine on June 25th, and Confederate leaders, aware of another effort underway to undermine the bastion, had set this party of men to work digging a “countermine.” Their goal was to intercept the Federals by running a shaft just above their operation. This would destroy the mine by collapsing the shaft.[2] The number of men involved in the Rebel effort is usually reported as “six or seven negroes, and a white overseer named Private Owen, with all of this group killed” …actually, all killed except Abraham.[3]

My partner in this fact-finding expedition, Mike Maxwell, writes:

It was about 1:30 PM, and Abraham had just arrived at the entrance to the countermine with his delivery when an unearthly “Boom” was followed by a sensation of weightlessness… and then, falling… rapidly falling. Abraham focused his eyes: the Rebel troops, the Federal troops, the city of Vicksburg were all crystal clear… and a long way down. The flying man did not know if swinging his arms and kicking his legs caused him to tumble; or if that rotation happened of its own accord. But the next thing he knew, his falling ended abruptly. And when he regained his senses, Abraham found himself on his back in a mound of dirt. There were men in blue running towards him, and they all seemed to be shouting…

Apparently, Abraham was interviewed, or at least quoted, after his experience. Perhaps a look at what are claimed to be his own words might shed some light on his origins. One quote is from Experience in the War of the Great Rebellion, “By a Soldier of the Eighty-First Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry (Edmund Newsome). On page 71, Abraham is quoted, “I think I went up ‘bout tree miles, sah, an’ as I was a comin’ down I met massa a gwine up.”

From another source:

“A DARKEY IN THE AIR”

Abraham, a full-blooded negro, and the only person who escaped with his life at the time the mine under Fort Hill at Vicksburg exploded, was at work with a number of the rebel soldiery “sinking a shaft” for the purpose of discovering any gallery that might have been “run by our miners” beneath their works.

The negro was blown a distance of nearly three hundred yards, and was, when picked up, in a most disturbed state of mind.

“De Lord, massa,”–quoth he—“tink neber should light—yah, yah! Went up ‘bout free mile. Ax a white man when I start whar were going, and de next I know’d he was just nowhere but all over.”[4]

The most interesting version of Abraham’s “after-action interview” comes from the Chicago Daily Tribune, July 14, 1862.[5] Soldiers of the 81st Illinois Volunteer Infantry offered their version of Abraham’s “capture.” The soldiers held him down until a superior officer could be informed of the situation. The federal officer closest to the incident was Brigadier General John “Black Jack” Logan, whose headquarters tent was only steps away. Logan questioned the terrorized Abraham:

“Why were you fighting us, the friends of the Black man?”

“I warn’t, Massa, swear to Jesus.”

“Where is your gun?”

“Doan’ hab no rifle… I was jus’ totin’ grub to da men.”[6]

General Logan must have been satisfied as to the truthfulness of Abraham’s story because Silas Trowbridge, Chief Surgeon for the 3rd Division, was called over to examine the stunned aeronaut. As Abraham sat up, lay down, and rolled over, Surgeon Trowbridge ran his hands along the man’s arms, and legs, expressing surprise to find nothing broken. However, when Abraham’s shirt was unbuttoned, his back and either side of his neck were found to be discolored and swollen. Abraham winced when his shoulders were touched. The back of Abraham’s head was also found to be badly bruised and swollen. With little knowledge of concussion at the time, all that Trowbridge prescribed was bed rest, sparing quantities of food and water, and time.[7]

Abraham was likely moved to the division hospital, but his status as both black and a civilian would have earned him his own tent. It has not been explicitly confirmed, but this is probably where the more enterprising Yankees set up their concession and charged money to other soldiers just to hear Abraham, the “Flying Black Man,” tell his story. There are many, many corroborating versions of the quotes above that appear in letters and memoirs.

The surrender of the city of Vicksburg was covered by the national newspapers such as Harper’s Weekly. Artist Theodore R. Davis did a sketch of Abraham for the paper that met with the former slave’s approval. The accompanying article quotes Abraham as telling Davis, “It’s da child o’ me.” He then demanded a quarter for his services as a model. Colonel Coolbough, an officer on McPherson’s staff, gave him a silver fifty-cent piece.[8]

_______________________________________________

[1] Annie Wittenmeyer, Under the Guns: A Woman’s Reminiscences of the Civil War. Boston: E. B. Stillings, 1895, 102-105. Also available in a reprint: https://www.amazon.com/Under-Guns-Womans-Reminiscences-Abridged/dp/1519041608#customerReviews.

[2] Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1863, 2.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lt. Col. Charles S. Greene. Thrilling Stories of the Great Rebellion, 286. This book was first published in 1864, then updated to include “Details of the Assassination of President Lincoln,” and the “Capture of President Jefferson Davis.” “The Story of Abraham” was included, based heavily on Harper’s Weekly article (August 8, 1863) by Theodore R. Davis.

[5] Chicago Daily Tribune, July 14, 1863, 2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Silas Thompson Trowbridge, M. D., Autobiography of Silas Thompson Trowbridge, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004, 145-147.

[8] Harper’s Weekly, August 8, 1863, 501.

I hope you have Part 3 detailing his post war life. Still hard to believe that he survived.

In 1860, Warren County took part in the Federal Census, conducted June – August, and totalled 20700 inhabitants (with 3680 of those living in Vicksburg.) And, of that figure of 20700 about 10,000 were recorded as “colored.”

Having just reviewed the “Free Inhabitants” segment of the Mississippi Census (still looking for the non-White record) I counted about 3200 Free Inhabitants of Vicksburg… which means about 480 were likely slaves. Of the 3200 residents, there were Free Blacks recorded (about thirty people) and in every case, except one, these Free Blacks were indicated as “mulatto.” The one exception was marked as Black; and in no case was “Abraham” recorded. It is still possible that Abraham was one of the 480 slaves living in Vicksburg. The 1860 Census runs across 82 hand written pages.

Warrenton’s Free Inhabitants take up four hand-written pages. And there is nothing of interest in that segment of the 1860 Census.

The remainder of the Warren County Census (96 pages) includes details of over 300 planters and farm owners (not including family members), and 120 or so “overseers.” Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina, are recorded (page 94 lines 19 and 20) and so is their overseer, I. McGill. Realizing that there is value in locating “Corporal Owens,” the overseer of Black men working for Lockett’s Engineers in constructing counter-mines, the remaining Warren County records were scrutinized: three male Owens resided in the county in 1860

Wm. Owens, farmer aged 64, with wife and two adult daughters (p.60 )

B. Owens, farmer (born MS) aged 46 with wife and 9 children (p.84 )

W. Owens, overseer (born MS) aged 30 with wife and 2 y.o. son, William (page 65 ).

Based on the above, my guess is William Owens (aged 64) is Father to W. Owens (aged 30) and either Father or brother to B. Owens (aged 46). William was too old for war service in 1863; and with occupation of “overseer,” W. Owens is likely the Corporal Owens who came to grief on July 1st 1863 at Fort Hill. If this is true, then his employer is likely indicated on the same page of the 1860 Census:

A. Hubbard

Jas. Beck

Boyd Ballard

Louisa Covington

P. Gee

Isaac and R. Whitaker

Of the above, W. Owens is listed between Ballard and Covington; so I would anticipate slaves belonging to Ballard or Covington, overseen by W. Owens, were employed in the Confederate Engineer Company, on July 1st 1863 working on the Fort Hill counter-mine when the Federal mine exploded at 1:30 p.m.

When the Slave Schedule was accessed the 10000 slaves were found to be recorded by AGE and GENDER (no names provided.)

…and this is the issue. He’s in there. We just don’t know where. All we can do at present is continue to consolidate information, be as transparent as possible (so others don’t have to start from zero), and keep at it. Maybe this is what I read from Abraham’s face–“Keep at it. Find me!”