A Conversation with Carol Reardon (part five)

(part five of a series)

(part five of a series)

To help commemorate Women’s History Month, I’m talking this week with Carol Reardon, one of the profession’s great public historians. Although she’s had an illustrious academic career, she mentioned yesterday how important it is to her to get out onto the battlefields. To me, that’s one of the things I’ve found so wonderful about working with Carol: not only her deep interest in being on the battlefields, but helping people connect with the battlefields. She’s written tour guides, given public programs and tours conducted staff rides—there’s a whole huge component about helping people connect.

Carol Reardon: That was a conscious decision on my part. You know the academic world, and you know what a department expects you to do, and you know what annual evaluations are like. If I had tried to do the field guides early in my career, I probably would never have gotten tenure or a promotion. Those field guides were not part of a plan. They were a fortuitous accident.

I was out on the battlefield—and this probably goes back to about, oh, say 2007 or 2008, somewhere along there—with David Perry from UNC Press. He had heard a lot of my stories, but he’d never been out on the field with me. Well, he came along on one of my field programs at Gettysburg, and he came up to me afterwards, and he said, “We have to figure out a way to bottle you and put you into a book, and get you out there for the world to hear.” He had had a lot of fun. And it became a running joke between us.

Then along about 2010 when he’s starting to think about what the press might do for the Sesquicentennial for the Civil War, he came back and revisited the idea with me. Now he said, “Seriously, why don’t we think about putting this together—a battlefield guide to Gettysburg, taking a lot of the stories that you told.”

I thought about it a whole lot. I mean, frankly, it sounded like a whole lot of fun. You know I love to do that—but I also know that the academic world doesn’t see that kind of work as particularly important. And certainly they don’t see that as innovative, cutting-edge scholarship. So I knew I just had to make a decision.

Well, I decided there’s no reason on earth why a battlegield guide can’t be excellent scholarship, even brand new scholarship in some elements, as well as accessible to anybody who wants to read it. I think we all know that there are plenty of books out there that are so narrow and so jargon-laden that they are impossible for even a fairly literate layman to read. I didn’t want that. I didn’t want it to just be a deep dive into military theory that nobody could understand. But I didn’t want it to be the “See Spot run” version of Gettysburg, either.

So an awful lot of thought went into how to set up the book. Even coming out with the six questions that we used to frame the field guide—What happened here? Who fought here? Who commanded here? Who died here? Who lived here? And what did they say about it later?—all of them pull on separate strings that come straight out of active scholarship. I mean, that last part, “What did they say about it later,” that’s the memory element.

The “who lived here?” part—that’s the reminder that this battle didn’t take place in a national park: it took place on people’s farms, and there’s a civilian story that is part of the whole narrative that otherwise, if we didn’t put it in there, visitors wouldn’t think about.

There was a reason for every bit of it. People who are open-minded enough about it—and, in this case, I mean professional historians who are open-minded enough about it—have come to appreciate that there is an awful lot of new scholarship in there.

Chris Mackowski: I think it was great.

Carol: Those who just don’t understand or—well, we know how academia works—just basically brush it off. I mean, I actually would get comments from various and sundry individuals like, “When are you going to do something serious again?” And, well, usually, my answer would probably not be printable.

Chris: That seems to overlook the whole idea that you can have fun doing what you’re doing. What’s wrong with that, you know?

Carol: I go back to something that James McPherson once wrote. It was in one of his books where he said, “Civil War historians have an unusual challenge because we have multiple audiences that we have to satisfy at the same time.”

Chris: We have to be conscious of different audiences all the time.

Carol: Yes. We have to satisfy the specialists in our field; we have to satisfy the historical profession at large; and we have to satisfy the great American public because they are the people who are actually going to buy the book and it may be the only book on this subject they’ll ever read. We do have an obligation to enlighten more than the circle of specialists around us—and that fits nicely into my general philosophy of life anyway.

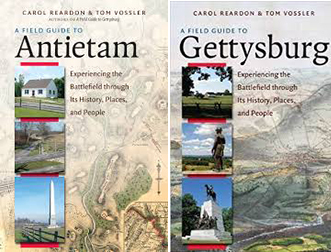

So, I had a ball writing the Gettysburg guide book and the Antietam guide book. Tom Vossler [her co-author] is one of my best friends down here in Gettysburg. We’ve done so many programs together that we could finish each other’s sentences in some places.

Tom had a 30-year career as an infantryman behind him, and he looks at a battlefield in a different way than I do.

Chris: Oh sure, yeah.

Carol: Just because he’s a combat veteran, he has different a different way of looking at them. His list of priorities are slightly different from mine. Now I thought, “Okay, that’s actually very useful here; there are things that I’m going to see, and there are things that he’s going to see.” So we talked about this, and we decided to do it as a joint product—not because either one of us felt we couldn’t do it alone, but because we thought that together it would be even better. Since we both had careers where we had to speak to great numbers of people who were not experts or specialists on Gettysburg, I figured that would help us keep the language and the theoretical concepts under control.

And it worked out. I’m responsible for most of the prose, but he’s responsible for a lot of the visuals and the maps and the places where we had to make sure that we’re oriented to the ground in just the right way. I mean, he was an infantryman. That was life or death to him.

Chris: Yeah.

Carol: He’s going to use those things even now. And I’m going to use the things that I’m good at. It worked out great, and I’ve been gratified to see how well it’s been received among our Civil War colleagues in the academic world. But there are academics beyond our field who basically thought I was wasting my time.

Chris: You used a word a few minutes ago that I think is so important: “accessible.” You have a consciousness about making history relevant and accessible, which I think is a problem in the field because not all academics necessarily keep those things in mind, but I think that that’s really been one of your key talents.

Carol: I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that I started leading staff rides at a very early age. I’ve been doing it for so long. That’s a Jay Luvaas thing, too—I keep looping him back in. Jay was probably more responsible than any other single individual for bringing the staff ride back to the United States Army and Marine Corps. I did not realize it at the time—there was no way for me to know that when he was taking us out on battlefield in the early ‘70’s–that he was honing his technique on us. We were his guinea pigs; we just didn’t know it.

We’d go to a place like the Wilderness, and he’d have us stand in a certain spot, and then he’d pull out this big, thick black book. It was the O.R., of course. He’d read a paragraph—of course, now I know it was somebody’s After Action Report—and he’d picked out a paragraph that was very descriptive, “We crossed an open field, there was a stone wall,” this, that and the other thing. So he’d read it, and then he’d just turn to us and say, “Can you see it?” If we were in the right spot, we’d say, “Yeah, yeah. There’s the field, there’s the wall,” and the little hill that he was talking about, “There it is.” And he’d just go, “Okay, that’s good.”

If he read it and asked us if we could see it and we could not, he’d relocate us maybe a couple hundred yards away and read it again, “Oh yeah, there it is.”

“Okay.”

What he was doing was picking out the stops and the stands so that when he brought groups of soldiers there, he’d have them in the right spot to see what was going on, so he could take the evidence of the O.R. and put it on the field and make it work. If you just read it in prose, you might not get a good visual about the terrain he described, but this made it possible for you to literally see it. It makes it accessible.

As I’m watching him do that, I thought it was really cool. That may actually be one of the reasons why I decided to go in the direction I did.

But then I ended up—at a very early age, at a very early stage in my academic career—being the visiting professor of military history down at the Army War College. I was filling a gap. When the person who was supposed to hold it had to turn it down, it happened to be the day I walked in to do research, and they went, “She’ll do.” And they basically plugged me into the hole.

But that year, that first year with the soldiers—and that was 1993/94—I got to go out into the field with Jay a lot. He sent me out on my first few staff rides solo with different groups that he couldn’t cover, and I just discovered, “Oh, I love this. This is so cool.”

But I also realized I wasn’t speaking to people who were part of my everyday academic life, so my vocabulary had to change, my examples had to change. I had to learn their professional military vocabulary as well as the academic vocabulary. I had to do things differently, and that opened me up to the possibilities. What if it’s a group that’s not academic or military? How do I tell that story to them? And it just progressed from there. I think it was the start doing staff rides that opened me up to the possibilities to take this to an even wider audience.

————

Working with so many military folks submerged Carol in a field—military history—that has traditionally been male dominated. When our conversation continues tomorrow, she’ll talk a bit about some of her strategies for navigating that field.

I used Jay Luvaas’s Tour books for my first really in-depth studies of Gettysburg and the Maryland Campaign battlefields. I have to try Ms. Reardon’s for comparisons.