A Conversation with Carol Reardon (conclusion)

(part seven of a series)

I’ve been talking this past week with Carol Reardon, who’s been one of the most successful Civil War scholars to bridge the gap between the academic world and the general public. Carol’s also been a trailblazer as a woman in a profession generally perceived to be male dominated. In that regard, I think she’s an especially effective role model for “emerging” female historians, and one of the main reasons I wanted to talk to her as part of ECW’s Women’s History Month commemoration.

As we conclude our conversation today, I asked her about that specific point.

Chris Mackowski: Before we wrap up, I want to ask one question about something we’ve sort of alluded to a couple times in this conversation, and that’s that stereotype—and I don’t know if it’s true or not—that “women don’t do military history.”

Carol Reardon: Mmm-hmm.

Chris: What’s your take on that?

Carol: One of the more recent times I was asked that question, somebody asked me if I were an anomaly being a woman in military history. And I responded with, “I don’t like ‘anomaly’; let’s try ‘pioneer.’” And people kind of chuckled about that.

I look at it this way, and this is the way I usually answer the question: there are many different ways to talk about military history. Soldiers engage in combat, armies and generals plan campaigns and fight battles, but nations go to war. And when nations go to war, that means everybody: women, children, men. That means it’s part of all of our stories. Why can’t I tell it?

If you watch the news today, and they talk about the war in, let’s say, Syria, when they’re showing you visuals, are they showing you fighters out in the field? Sometimes. But what are you just as likely to see? Refugees, women and children and civilians. Whenever we see what’s going on in Afghanistan, and hear talk about some kind of a terror bombing, who are the victims? They aren’t alwaysTaliban or uniformed members of the Afghan army or American advisors. They are students or policemen or women going to market. Basically, if you’re talking about military history these days, you’re talking about much more than battles and leaders and soldiers.

We used to make the distinction many years ago between “new” military history and “old” military history. “Old” was drums and trumpets, the history of battles and generals and leaders, and “new” was the integration of all the different elements of national power, in which you could talk about war as not just being a military thing, but also one that had political and economic and social and cultural dimensions as well. For a while, we went through a phase where they said new military history was softer, it wasn’t serious military history—it was, like, de-blooded military history. Women might be able to contribute there. Maybe. But, now, of course, the practical reality is, when we look around us today, when nations are at war, there are so many complex elements that touch everybody’s life. Military History is all-inclusive.

If I offer up that observation to an audience of non-academic Civil Warriors, there are going to be plenty of people in that audience whose eyes are going to roll back a little bit, “Oh, here we go. We’re getting a PC explanation.” So if I need to do so, I take them back to right after the battle of Antietam, when the editor of the newspaper up in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, wrote an editorial in which he said—I’m going to paraphrase it—“We are all in this war. Whether we are on the frontlines or whether we are waiting to hear about his fate back here in central Pennsylvania, we are fighting this war. Whether we are working extra hard in the fields to let another person go to the front, we’re involved in this war. Whether our hearts are waiting for words about a bullet that severed the heartstrings between us and a loved one, we are in this war.”

That was something that really resonated with me. This is an editor in 1862 who’s basically saying this was not simply a fight between armies. It was a war between nations and people, and that includes all of us, and that includes me, and that makes me a perfectly legitimate military historian.

Chris: So, my final question for you. What advice would you offer to a young woman in particular, but any young historian, who is thinking about a career in Civil War history?

Carol: Whoa. It’s a challenge these days. Confronted with the realities of the profession yourself, you know, it’s awfully tough.

Chris: Right.

Carol: But for somebody who wants to get into Civil War history, first of all, take advantage of any opportunities while you can, in and out of school, to visit as many Civil War-related sites as you can because it’s building not just knowledge but context and variety. Don’t limit it to battlefields. Go visit a southern plantation. Visit the Harriet Tubman location. Go to Frederick Douglass’ house. Go to the homes of the Civil War-era presidents—not just Lincoln, but go to Garfield’s house because he fought during the war. Get an idea of the variety of personal experiences that were involved in this war by visiting the sites that were important to them.

That’s one of the reasons why I like to go to battlefields. I mean, there’s a visual component to what we do that we can only appreciate if we go on-site. The power of place is really important to understanding this war. If you’re a northerner, drive through the south. If you’re a southerner, visit some northern communities. Go up to Boston and take a look at the monuments of the 54th Massachusetts. Things like that.

That’s not going to get you any academic credit or anything like that, but it builds up a storehouse of experiences on which you can build.

In the academic world, first of all, take any of the Civil War courses you can, but go back to the same advice I was given: don’t be a one-war wonder. Your understanding of the Civil War and the experiences of the nation, the people, the armies, the soldiers, writ large or writ small, is only going to get better if you understand more about the experience of war through the ages. So, don’t shy away from that.

Third, hone your research skills. There’s so much that’s available to you on the internet these days that there’s no excuse why you can’t go out and start familiarizing yourself—and even using that at any possible juncture, such things as Civil War-era newspapers and digitized letters and documents that are increasingly appearing on the internet. But don’t limit yourself to that. Take yourself to an archive. Go to your state archives. Go to your local historical society, and learn the thrill of picking up a manuscript that was first written by a soldier or a player back in the 1800’s.

I can still remember one of those “a-ha” moments for me. I was actually working on my master’s thesis, and I happened to go to the Southern Historical Collection at Chapel Hill, and I was looking at a file that came from the E. Porter Alexander Collection. I’m looking for artillery information, and I pick up this one letter and I’m holding it in my hands, and I’m looking at the handwriting, and I’m thinking to myself, “I’ve seen that handwriting before.” I can’t quite identify it, then I turned the letter over and realize that the paper was signed “R. E. Lee.” I dropped it like a hot potato, like, I shouldn’t be holding this. It was just one of those things: “I have just held something that Robert E. Lee himself wrote.” And, wow, that was a moment.

If this isn’t fun for you, you are in the wrong business. Go out there and find those moments. Become a part of the Civil War community—the scholarly community and the public community, as well. There are Civil War roundtables that are accessible to the public. Gettysburg College has a Civil War club. If you don’t have a Civil War club, join the history club instead. Any breadth and context is great.

Probably one of the most important things you can do beyond that, other than being very good at what you do and having a sense of humor about yourself, is find yourself a mentor or several mentors, people who have already followed the path that you now want to follow, and ask them questions, and ask their advice. Nobody does what we do in this business alone. We might do our work alone, be all by ourselves when we do our writing, but to the point where you sit down and start that writing, you are the product of a whole lot of other people and a whole lot of other influences. And the more of them you can get, the better it is.

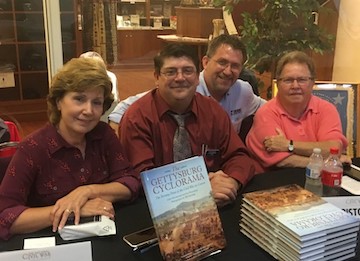

Speakers coming to your college to talk about a Civil War thing—you make sure you’re there to hear it. If they’re going to have a book signing, if there’s some kind of an opportunity to speak with them, go speak with them. You never know what you’re going to learn or where you’re going to learn it, but you’ll be better off for it.

There is a large element of luck in how far down the road you can go, but luck depends on a whole lot of hard work to put you in that position to take advantage of it when the opportunity comes. And don’t forget summer internships at Civil War sites.

Now, that’s a long answer, but . . .

Chris: It’s gold, Carol, gold.

Carol: But, that’s basically what I tell folks. I’m not quite so cynical that I’ll just simply say, “Don’t do it; run away.” I think I’ve been re-inspired by the students I’m dealing with right now.

I mean, I’m here in Gettysburg, and I’m dealing with students who are taking a Civil War-era studies introductory course. It’s not required for any of them. Each one of them has chosen to be there, and some of them are so excited. It’s a lot of fun. I had a student in class last semester who showed up every day in class in a different uniform. There are a lot of other schools where, if he’d shown up in a uniform, he would have been heckled out of that classroom in a heartbeat. But, here, I turned him into a teaching tool: “What are you wearing today? Please explain it.” And the students started asking him questions. And when I realized that I wasn’t necessarily the only expert in the room, and that he had something to contribute and everybody gave him that kind of authority and recognized his authority in those things, I was sitting there thinking, “Cool—this is really good stuff happening.”

Chris: Yeah, wow.

Carol: So you never know when that opportunity is going to come and where it’s going to lead or where you’re going to find inspiration. And it doesn’t always flow from top down. Sometimes it comes from bottom up.

So, there you go!

Thank you to both Chris and Carol. This conversation series has been inspiring on so many levels. Thank you, thank you, THANK YOU!

My pleasure, Sheritta. The whole idea is to offer a little inspiration, so I’m glad you found some. Carol is such a great historian and great person. It’s always fun to chat with her, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to share that conversation.