Ending The War: “That’s Meade!”

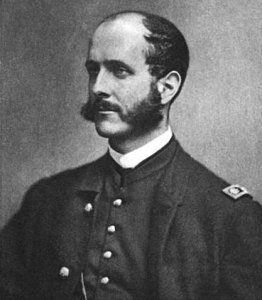

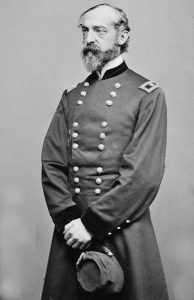

Many accounts of Appomattox focus on Grant and Lee, but Theodore Lyman left a fascinating record the Army of the Potomac’s commander on April 9, 1865. Lyman had reached out to General George G. Meade in August 1863, requesting to serve on his staff. Meade accepted the offer, and as Lyman served at headquarters for the last year and a half of the war, he kept a diary—offering some “insider” perspective on Meade and other Federal officers. Lyman had admiration for Meade, but he did not “hero-worship” him.

The journal entry for April 9 shows Meade ready to fight to the end and making a speedy recovery from illness. It also reveals a moment of triumph and solider loyalty for the commander of the army of the Potomac.

April 9, 1865

We all were up, according to habit, about daylight, with horses saddled, having staid near Stute’s house the night. In reply to a summons from Grant, Lee has sent in a note to say that he would meet Grant at ten A.M. to confer on measures for peace. The Lieutenant-General answered that he had no authority in the premises and refused the interview; but repeated his offer to accept the army’s surrender on parole. Indeed, we suspected his affairs were from bad to worse, for last night we could hear, just as sunset, the distant cannon of Sheridan. He, with his cavalry, had made a forced march on Appomattox Station, where he encountered the head of the Rebel column (consisting, apparently, for the most part of artillery), charged furiously on it, and took twenty cannon and 1000 prisoners; and checked its progress for that night, during which time the 24th and 5th Corps, by strenuous marching, came up and formed line of battle quite across the Lynchburg road, west of Appomattox C.H.

Betimes this morning, the enemy, thinking that nothing but cavalry was in their front, advanced to cut their way through, and were met by the artillery and musketry of two crops in position—(Ah! There goes a band playing “Dixie” in mockery. It is a real carnival!) This seems to have struck them with despair. Their only road blocked in front, and Humphrey’s skirmishers dogging their footsteps! Well, we laid the General [Meade] in his ambulance (he has been sick during the whole week, though now much better) and at 6:30 A.M.

The whole Staff was off, at a round trot—(90 miles have I trotted and galloped after that Lee, and worn holes in my pantaloons, before I could get him to surrender!). An hour after, we came on the 6th Corps streaming into the main road from the upper one. A little ahead of this we halted to talk with General Wright. At 10:30 came, one after the other, two negroes, who said that some of our troops entered Lynchburg yesterday; and the Lee was now cut off near Appomattox Court House. This gave us new wings! An aide-de-camp galloped on, to urge Humphreys to press the pursuit, and all wagons were ordered out of the road, that the 6th Corps might close in immediately on his rear.

Away went the General again, full tilt along the road crowded by the infantry, every man of whom was footing it, as if a lottery prize lay just ahead! A bugler trotted ahead, blowing to call the attention of the troops, while General Webb followed, crying, “Give way to the right! Give way to the right!” Thus we ingeniously worked our way, amid much pleasantry. “Fish for sale!” roared one doughboy. “Yes,” joined in a pithy comrade, “and a tarnation big one, too!” The comments on the General were endless. “That’ s Meade.” “Yes, that’s him.” “Is he sick?” “I expect he is; he looks kinder wild!” “Guess the old man hain’t had much sleep lately.”

The heavy artillery firing we had earlier heard, now had suddenly ceased, and there was a perfect stillness—a suspicious circumstance that gave us new hope. Somewhat before noon we got to General Humphreys, some five miles east of the Court House and at the very head of his men. He reported that he had just struck the enemy’s skirmish line, and was preparing to drive them back. At that moment an officer rode up and said the enemy were out with a white flag. “They shan’t stop me!” retorted the fiery H.; “receive the message but push on the skirmishers!”

Back came the officer speedily, with a note. General Lee stated that General Ord had agreed to a suspension of hostilities, and he should ask for the same on this end of the line. “Hey! What!” cried General Meade, in his harsh, suspicious voice, “I have no sort of authority to grant such suspension. General Lee has already refused the terms of General Grant. Advance your skirmishers, Humphreys, and bring up your troops. We will pitch into them at once!”

But lo! Here comes now General Forsyth, who had ridden through the Rebel army, from General Sheridan (under a flag), and who now urged a brief suspension. “Well,” said the General, in order that you may get back to Sheridan, I will wait till two o’clock, and then, if I get no communication from General Lee, I shall attack!” So back went Forsyth, with a variety of notes and dispatches. We waited, not without excitement, for the appointed hour. Meantime, negroes came in and said the Rebel pickets had thrown down their muskets and gone leisurely to their main body, also that the Rebel were “done gone give up.”

Presently, the General pulled out his watch and said: “Two o’clock—no answer—go forward.” But they had not advanced far, before we saw a Rebel and Union coming in. They bore an order from General Grant to halt the troops. Major Wingate, of General Lee’s Staff, was a military-looking man, dressed in a handsome grey suit with gold lace, and a gold star upon the collar. He has courageous, but plainly mortified to the heart. “We had done better to have burnt our whole train three days ago”; he said bitterly. “In trying to save a train, we have lost an army!” And there he struck the pith of the thing.

And so we continued to wait till about five, during which time General Humphreys amused us with presents of Confederate notes, of which we found a barrel full (!) in the Rebel wagons. It was strange spectacle, to see the officers laughing and giving each other $500 notes of a government that has been considered as firmly established by our English friends!

About five [o’clock] came Major Pease. “The Army of Northern Virginia has surrendered!” Headed by General Webb, we gave three cheers, and three more for General Meade. Then he mounted and rode through the 2nd and 6th Corps. Such a scene followed as I can never see again. The soldiers rushed, perfectly crazy, to the roadside, and there crowding in dense masses, shouted, screamed, yelled, threw up their hats and hopped madly up and down! The batteries were run out and began firing, the bands played, the flags waved. The cheering was such that my very ears rang. And there was General Meade galloping about and waving his cap with the best of them! . . .

Post-script from a post-Appomattox letter on April 23, recalling when Meade met Lee:

. . . As we turned down the road again, we met him [General Lee] coming up, with three or four Staff officers. As he rode up General Meade took off his cap and said: “Good-morning, General.” Lee, however, did not recognize him, and, when he found who it was, said: “But what are you doing with all that grey in your beard?” To which Meade promptly replied: “You have to answer for most of it!”

Source:

Lyman, Theodore. With Grant & Meade: From the Wilderness To Appomattox. University of Nebraska, 1994. (Pages 355-360)

General Meade never got the credit he deserved. General Grant always used him as a scapegoat for his own blunders.

Nice post to remind us of what a tremendous burden Meade had on his hands for so long. I agree he has been underrated for too long.

Agreed, even before becoming the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Meade was an EXCELLENT division commander in nearly all the largest battles in the east. Made the only Union breakthrough at Fredericksburg through Stonewall Jackson’s troops, defeated Lee at Gettysburg after only 3 days on the job, and held his own in the months prior to Grant’s arrival in the east. Didn’t want command of AOP (felt Reynolds should have taken it), but did a admirable job when he did, even with several of his corps commanders trying to undercut him and get him fired. Never got the credit he deserved… You Go you “goggle-eyed snapping turtle..!!!”

Meade was an excellent brigade commander too. His Penn Reserve brigade under his leadership fought well at Glendale and Meade was shot three times, including a wound to his internal organs that would eventually kill him 10 years later. At Second Bull Run, the brave stand of the Penn Reserves in the Sudley Road allowed the rest of the army to retreat unmolested.

Beware Pres. Trump what a hating press can do to you .I n this case a great career and service to his country dis missed by a biased press . .More so then by Gen. Grant I believe