The Battle of Bank’s Ford and a Preview of Gettysburg

May 4, 1863, might have been one of the most frustrating days of the war for Robert E. Lee—no small bar considering some of his other frustrating days. But with the Federal Sixth Corps pinned against the Rappahannock River after its failed attempt to break past Salem Church the previous day, Lee had a golden opportunity to crush a significant portion of the Army of the Potomac.

Instead, Lee would miss the chance due to poor communication and coordination among his subordinates in an eerie preview of events that would unfold in Gettysburg on July 2.

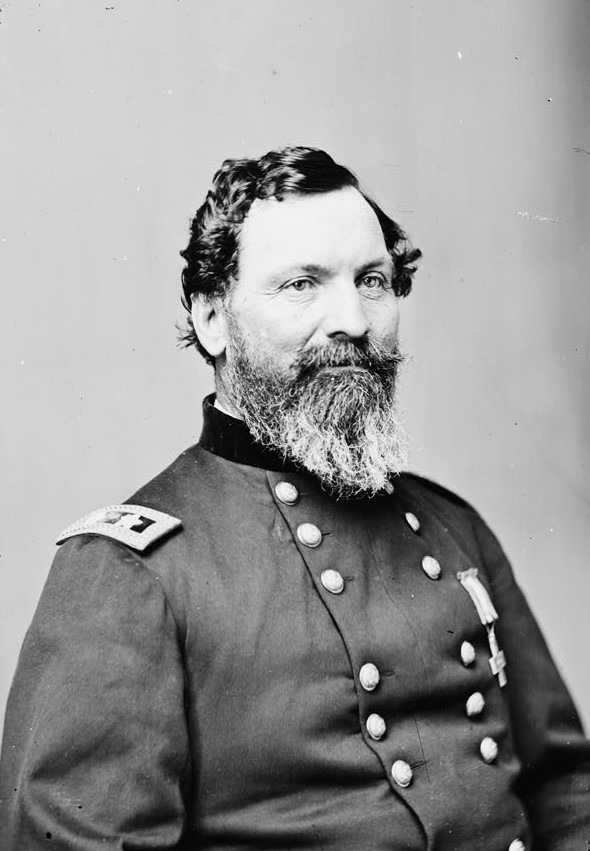

“[T]he old man seemed to be feeling so wicked,” artillerist E. Porter Alexander said of Lee on May 4. He had spent three days pummeling Joe Hooker’s army at Chancellorsville and then had turned to his rear to fend off an advance by Hooker’s Sixth Corps, under the command of John Sedgwick. The three days had presented crisis after crisis—including the wounding of Second Corps commander “Stonewall” Jackson—and had resulted in the second-bloodiest day of the war. News of Sedgwick’s advance came just as Lee thought he’d driven Hooker from the battlefield.

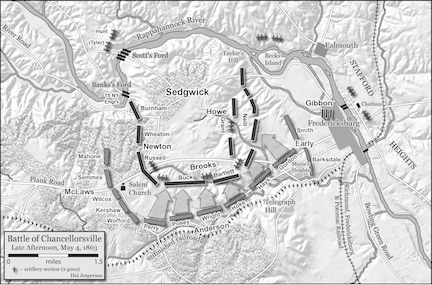

Sedgwick, for his part, had been given the impossible task of advancing to Fredericksburg from the south, overwhelming Confederate defenses there at the infamous Stone Wall and Sunken Road of Marye’s Heights, and then advance to Hooker’s rescue at Chancellorsville 10 miles to the west. Sedgwick managed to do much of what Hooker had expected, but on his march from Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville, he was intercepted by the Confederate brigade of Cadmus Wilcox. Wilcox conducted a brilliant delaying action that allowed Lee to get troops into place along a small ridge called Salem Heights adorned by a small brick Baptist church, Salem Church. The resulting battle stopped Sedgwick in his tracks, but the stolid Sixth Corps commander managed to hunker down into a tight defensive “U” after night brought an end to the fighting.

Lee had three divisions at his disposal: Lafayette McLaws, Richard Anderson, and Jubal Early. McLaws and Anderson both belonged to the Confederate First Corps, but the corps commander was in southeast Virginia with his other two divisions on a foraging mission, so Lee acted as the de facto corps commander on the field. Early’s division, part of Jackson’s Second Corps, had been the army’s rear guard in Fredericksburg. After Sedgwick brushed the division aside in his push through the city, Early simply slid back into position behind Sedgwick and closed in behind in. This, in turn, forced Sedgwick to constrict into his “U” for defense.

Sedgwick’s “U” sat within a bend of the Rappahannock River. McLaws and Early sealed Sedgwick in. The position had advantages for Sedgwick, though. The river protected his flanks, and his position allowed him to protect Bank’s and Scott’s Fords—his potential routes of escape.

Sedgwick’s “U” sat within a bend of the Rappahannock River. McLaws and Early sealed Sedgwick in. The position had advantages for Sedgwick, though. The river protected his flanks, and his position allowed him to protect Bank’s and Scott’s Fords—his potential routes of escape.

However, Hooker was unclear about Sedgwick’s exact situation. “If it is practicable for you to maintain a position on the south side of the Rappahannock, near Banks’ Ford, you will do so,” the army commander ordered. “It is very important that we retain a position at Banks’s Ford.”

Despite the position’s advantages, the orders for Sedgwick to hold tight made things look bleak enough for the Sixth Corps that one of Sedgwick’s officers feared that the corps was “going to close its career today.”

“I will tell you a secret,” Sedgwick replied. “There will be no surrendering.”

It should have been a slam-dunk for Lee. While the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia held Hooker’s main force at bay, Lee would crush Sedgwick with Early and McLaws.

Yet the day passed with little more than skirmishing. Lee—who had to direct intelligence gathering himself because his cavalry chief, Jeb Stuart, led the force that held Hooker in check—discovered a large gap between McLaws and Early. He filled it with three divisions from Richard Anderson’s division, but that took more time.

More time passed as McLaws and Early each waited for the other to start Lee’s planned assault—a communication mix-up that Lee had to then sort out. McLaws, the senior division commander on the field, should have but did not take the initiative and so Lee turned to the ever-aggressive and ever-dependable Early.

The attack didn’t start until 6:00 p.m., and although Confederate artillery rained down on Sedgwick’s vulnerable “U.” “[T]hey piled on us from three sides as thick as bees around a hive,” one Federal soldier said.

Fighting continued well after dark, with the Federal position slowly contracting under the pressure. “[I]f we let them alone until morning we will find them again intrenched,” Lee said, “so I wish to push them over the river tonight.” He ordered a night attack, which pressured Sedgwick even more. After sending urgent messages to Hooker, the army commander authorized the Sixth Corps commander to begin a withdrawal. “Cover the river, and prevent any force crossing,” Hooker said.

Sedgwick executed an almost perfect withdrawal. Stymied by darkness, fog, and the fog of war, Lee was unable to deliver his hoped-for knock-out, and by dawn, the last of the Federals were safely on the river’s north bank.

Had he been feeling “so wicked” at the start of the day, imagine Lee’s temperament on the morning of May 5 when he found the Federals gone.

In a way, the troubles Lee experienced at the battle of Bank’s Ford could serve as a preview in microcosm of his troubles on July 2, 1863. Most obviously, in both situations, Lee had the exterior position: the exterior of the “U” in May and the exterior of the fishhook in July.

In both situations, communication between commands caused important breakdowns that prevented smooth transition from one command when it came time to hand off the baton to the next. In May, McLaws and Early, who came from different corps, didn’t mesh; in July, the hand-off from Longstreet Corps to Hill’s in the attack against Cemetery Ridge led to a breakdown in momentum. May 4 even had all three of the eventual Gettysburg Corps represented: McLaws (First), Anderson (moved to the newly created Third), and Early (Second). Lee’s inability in both instances to ensure smooth communication between the commands led to delays and less-than-effective attacks. We can’t press that comparison too far because Early and Anderson, in particular, did well at Bank’s Ford, but in both situations, Confederates came close but not close enough.

Lee did seem to learn from lessons from Bank’s Ford, although it could be debated whether they were the right lessons. At Gettysburg, Lee better understood McLaws’s strengths and weaknesses and used a heavier hand with him when giving orders, even superseding Longstreet. Lee directed McLaws to lead Longstreet’s march on July 2—thereafter a source of contention between army, corps, and division commanders. Lee’s experience as an ersatz corps commander may have complicated his army’s overall performance on that day.

Lee wouldn’t get another pull at the Sixth Corps, although the Sixth Corps would eventually get a pull at Lee—on November 7 at Rappahannock Station. Uncle John’s men would earn themselves some payback for the abuse Lee dealt them in May.

Enjoyable read.

Great piece Chris. I am glad your judgement that Sedgwick did the best he could in response to Hooker’s orders is in accord with my take on this in my account of 2nd Fredericksburg in “No Flinching From Fire,” my account of the 65th NY. I thought after going through Hooker’s confusing and inconsistent orders that Sedgwick doesn’t deserve blame for not getting to Chancellorsville. In fact one can argue Hooker basically left HIM to his fate.

I still like that during the assault on Sedgwick’s line, the Louisiana Brigade under Harry Hays managed to punch through two lines of Federals and I think it was Early who got excited and shouted “Those boys can steal as much as they want!” They couldn’t maintain their progress, but still one of those shining moments for Lee’s Tigers.

Nice article and connection to Gettysburg. Use of interior lines really helped Sedgwick from ever really feeling overwhelmed. And, much like Gettysburg, I don’t think the Confederates were really able to pin them down with converging artillery fire