The Second Seminole War as a Civil War Training Ground

In the popular narrative of the coming of the Civil War, the U.S.-Mexico War is often identified as the military crucible through which many of the war’s most famous battlefield leaders first passed—gaining lessons in leadership and combat operations under the watchful eyes of commanding officers Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. In the course of working on my dissertation, however, I’ve come to wonder whether it wouldn’t behoove more Civil War historians to cast their eyes back to the Second Seminole War to understand how men such as William Tecumseh Sherman, George Henry Thomas, Joseph E. Johnston, and Robert Anderson learned to be soldiers and wage long, multi-faceted wars.

In the popular narrative of the coming of the Civil War, the U.S.-Mexico War is often identified as the military crucible through which many of the war’s most famous battlefield leaders first passed—gaining lessons in leadership and combat operations under the watchful eyes of commanding officers Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. In the course of working on my dissertation, however, I’ve come to wonder whether it wouldn’t behoove more Civil War historians to cast their eyes back to the Second Seminole War to understand how men such as William Tecumseh Sherman, George Henry Thomas, Joseph E. Johnston, and Robert Anderson learned to be soldiers and wage long, multi-faceted wars.

Fortunately for Civil War historians, the study of the Second Seminole War is in the midst of a robust revival. While John K. Mahon’s History of the Second Seminole War (published 1967) remains the best treatment of military operations during the war, C. S. Monaco’s The Second Seminole War and the Limits of American Aggression (2018), pushes historians to consider how settler colonialism and the push for American empire drove soldiers and officers to adopt aggressive tactics and wage a war of occupation that targeted both the Seminole Nation (including non-combatants) and African American maroon communities, as well as the environment. A quick glance at recent works published in Civil War history reveals studies of the environment, of refugees, of occupation, of the limits of war (and the transgressions against them); in other words, if soldiers were thinking about these issues during the Civil War, it likely wasn’t for the first time.

Still, I always try to keep my caution bulb lit when I read about Civil War officers spending their earliest professional years in Florida. One temptation in trying to determine how the personalities and military viewpoints of famous commanders formed is trying to read the evidence in reverse. We know William T. Sherman pursued a hard war during his march through Georgia and the Carolinas, but we cannot definitively say he adapted that policy from one he participated in during his service in Florida. With this is mind, there are still several compelling examples from the Second Seminole War for any historians interested in understanding the development of American military ideology during the antebellum era and its effect on the Civil War.

Still, I always try to keep my caution bulb lit when I read about Civil War officers spending their earliest professional years in Florida. One temptation in trying to determine how the personalities and military viewpoints of famous commanders formed is trying to read the evidence in reverse. We know William T. Sherman pursued a hard war during his march through Georgia and the Carolinas, but we cannot definitively say he adapted that policy from one he participated in during his service in Florida. With this is mind, there are still several compelling examples from the Second Seminole War for any historians interested in understanding the development of American military ideology during the antebellum era and its effect on the Civil War.

In his letters written during the Mexican American War, Robert Anderson—the future hero of Fort Sumter—lamented the lack of expediency exhibited by the federal government in sending troops to bolster Winfield Scott’s forces at Vera Cruz. “Had we 30,000 men and Genl. Taylor 20,000,” he explained to his wife, Eliza, “the War might soon be closed.” He hoped the government would “would act vigorously upon the advice given by Father to it before the breaking out of the Florida war.”[1] Anderson had a unique perspective (and particular loyalties) in comparing the mobilization efforts for the two conflicts. Anderson’s father-in-law, Colonel Duncan L. Clinch, urged the federal government to maximize its commitment of troops to Florida in 1835. The federal government followed Clinch’s advice and shifted more than two-thirds of its troops from the Eastern Seaboard to Florida. Eventually 10,000 Regulars and upwards of 30,000 militia served in the conflict, which was fought over a theatre of 65,000 square miles.[2] The strategy that helped to bring about Union victory certainly shared Anderson’s embrace of applying superior manpower resources against a numerically inferior foe.

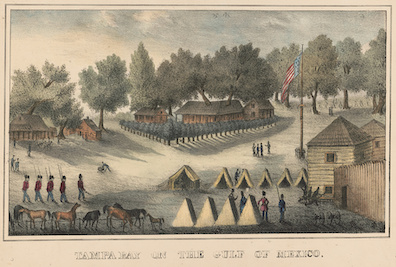

George H. Thomas’s Second Seminole War correspondence can perhaps help to shed light on why the ‘Rock of Chickamauga’ decided to fight for the Union, despite claiming Virginia as his natal state. Like many men who faced a difficult decision between fighting for the United States or the Confederacy in 1861, Thomas possessed multiple, overlapping loyalties—to the nation, to his state, and to his family.[3] In siding with the Union, he broke two of those ties for the one that his Second Seminole War era correspondence suggests he believed to be paramount—his duty to serve the United States. By most accounts Thomas felt miserable during his time in Florida, and he worried privately that he would not get to prove his worth in battle—as an 1841 letter suggests. Despite these misgivings Thomas assumed the duties of “commissary, quartermaster, ordnance officer, and adjutant” at his small post on the edge of the Florida Everglades, Fort Lauderdale.[4] Despite the tedium (Thomas did, eventually, see combat), Thomas never complained about the military tasks he was asked to perform or about the political and social causes for the war. He simply did his duty. Thomas’s decision to remain loyal to the Union has received far less historical scrutiny than Robert E. Lee’s decision to join the Confederacy. A fuller appreciation of Thomas has long been needed, and any careful study of his loyalty should begin by considering his service in the Second Seminole War.

Joseph E. Johnston’s Second Seminole War experience likely contributed more to Johnston’s own self-regard than it did to his understanding of how to lead troops in battle. Johnston left the army in 1837 to train as a civil engineer, after serving of the staff of Winfield Scott during Scott’s brief period in command of operations in Florida. While in Florida as a civilian, Johnston came under fire and decided to rejoin the Regulars in order to serve in the Topographical Corps. Johnston had “no command of troops” during this second stint in Florida.[5] Johnston did go on to command volunteers in Mexico, but between 1848 and 1861 he only spent one year in command of regular troops. Johnston clearly gravitated toward commands that placed him on the “staff” side of the army, rather than the “line.” This meant he gained swift promotion through the army’s ranks (appointed Brigadier General in 1860), but little experience—and also meant that three men ranked ahead of him in the new Confederate Army, to Johnston’s bitter disappointment. Regardless of one’s opinions of Johnston’s Civil War generalship, it is fair to say that beginning in the Second Seminole War Johnston set himself on a path that rewarded him with little experience in command of men and armies.

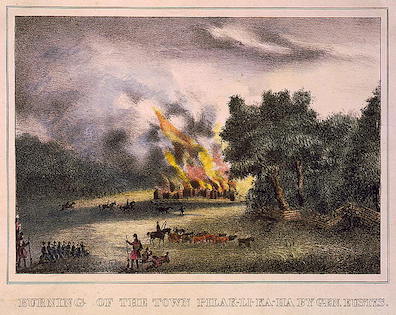

William Tecumseh Sherman’s fondness for recording his thoughts and opinions on a variety of military subjects mean that he left a small but compelling record of his experiences during the Second Seminole War. Sherman spent two years in Florida after graduating West Point in 1840. While describing Florida’s flora and fauna, Sherman also took time to detail his personal opinions of the war for his brother, John, a future U. S. senator. Readers familiar with Sherman’s postwar career would likely find his blistering critique of federal Indian policy surprising. Sherman declared the Second Seminole War “the same as all our Indian wars” and derided the government for expecting soldiers to wage war against an enemy that was highly mobile and more familiar than American troops with the terrain.[6] Two years in Florida helped convince Sherman that Indian wars were a waste of resources and men. But Sherman also represented an army that pursued the Seminole to the absolute limits of their resistance—a strategic vision that Sherman would refine in collaboration with his great friend Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War.[7]

Sherman boasted to his family in November 1841 that his regiment in Florida “caught more Indians and destroyed more property in a fair method than the rest of the army.”[8] On January 1, 1865, Sherman filed an official report that stated matter-of-factly, “I estimate the damage done to the State of Georgia and its military resources at $100,000,000; at least $20,000,000 of which has inured to our advantage, and the remainder is simple waste and destruction.” Whether or not he learned to wage this “hard species of warfare” in Florida, there is little doubt Sherman took pride in defeating his enemy as completely as he could, as well as in recognizing the achievements of the men under his command.[9]

A half dozen other prominent Civil War officers served in Florida, among them George G. Meade and Joseph Hooker, who went on to fight for the Union, and Braxton Bragg and Jubal Early, who sided with the Confederacy. Though the cohort of West Point graduates who served in Mexico is far larger, historians should not forget about the Second Seminole War when they assess the development of the antebellum army. More to the point, examining the experiences of Civil War officers during the Second Seminole reminds us that commanders came to the Civil War with varying degrees of experience and expertise (even if they shared an educational background) and that whenever we claim that the sectional conflict represented a great innovation in combat, or tactics, or the civilian experience, there are probably earlier examples that can prove instructive and worth accounting for.

A half dozen other prominent Civil War officers served in Florida, among them George G. Meade and Joseph Hooker, who went on to fight for the Union, and Braxton Bragg and Jubal Early, who sided with the Confederacy. Though the cohort of West Point graduates who served in Mexico is far larger, historians should not forget about the Second Seminole War when they assess the development of the antebellum army. More to the point, examining the experiences of Civil War officers during the Second Seminole reminds us that commanders came to the Civil War with varying degrees of experience and expertise (even if they shared an educational background) and that whenever we claim that the sectional conflict represented a great innovation in combat, or tactics, or the civilian experience, there are probably earlier examples that can prove instructive and worth accounting for.

————

Sources:

[1] Robert Anderson, An Artillery Officer in the Mexican War, 1846-7 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911), 196.

[2] The federal government mobilized 40,000 men to secure a territorial claim to 65,000 square miles. The United States gained 525,000 square miles of territory in the Mexican Cession, in a war that 30,000 regulars and 73,000 volunteers fought in. One soldier served for every 1.6 square miles gained in Florida, while in Mexico one soldier served for every 5.1 miles added (though they often fought their battles outside of the territory that became the United States). Thus, Anderson made a very salient point about the investment of resources in terms of the size of the task—and an argument could be made that the government invested more manpower per square mile in Florida than it did in Mexico.

[3] See Gary W. Gallagher, Becoming Confederates: Paths to a New National Loyalty (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013) for an explanation of how two other Virginians (and one North Carolinian) negotiated a similar decision.

[4] Thomas quoted in Christopher J. Einolf, George Thomas: Virginian for the Union (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 33.

[5] Bradley T. Johnston, A Memoir of the Life and Public Service of Joseph E. Johnston (Baltimore: R. H. Woodward, 1891), 10.

[6] William T. Sherman to John Sherman, March 31, 1841, William T. Sherman Papers: General Correspondence, 1837-1891; 1837, Dec. 6-1848, Feb. 18, Library of Congress; accessed via https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39800.001_0023_0348/?sp=37.

[7] Most historians of the Second Seminole War identify the period between 1837 and 1840 as vital for breaking Seminole resistance. The American commander at the time was Zachary Taylor, a man who functioned as a role model for both Grant and Sherman in their military careers. Grant paid tribute to Taylor in his memoirs, saying “General Taylor was not an officer to trouble the administration much with his demands….No soldier could face either danger or responsibility more calmly than he. These are qualities more rarely found than genius or physical courage.” Sherman, during the Vicksburg campaign, observed “Grant is as honest as old Zack Taylor.” [Ulysses S. Grant, Memoirs and Selected Letters, ed. William S. McFeely (New York: Library of America, 1990), 69; William T. Sherman, Sherman’s Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860– 1865, ed. Brooks D. Simpson and Jean V. Berlin (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999) 466.]

[8] Sherman quoted in Jane F. Lancaster, “William Tecumseh Sherman’s Introduction to War, 1840-1842: Lesson for Action,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 72, No. 1 (July 1993): 69.

[9] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 127 vols., index, and atlas (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), ser. 1, vol. 44, 13.

Very interesting and thoughtful post.

–Chris Barry

Another interesting development regarding William T. Sherman and the Second Seminole War: towards the end of that emergency, as First Lieutenant Sherman returned north, he stopped in Charleston and happened upon the drill being conducted by militia officer Stephen A. Hurlbut of the 17th South Carolina Militia (Charleston Reserves.) Hurlbut had joined too late to take active part in the war in Florida; he was merely involved in training potential fighters in his home State. But his drill routine was sufficiently polished to impress the West Point-trained Sherman, and the two struck up a friendship that endured for the next twenty years.

Stephen Hurlbut moved to Illinois in 1845 and practiced Law, became involved in politics, supported Abraham Lincoln for President in 1860. During March 1861 Hurlbut returned to South Carolina at behest of President Lincoln on a fact-finding mission; upon his return, in reward for revealing the “true state of affairs at Charleston,” Hurlbut was made Brigadier General of Volunteers, and served in command of troops from Illinois and Iowa in Northern Missouri. But, Stephen Hurlbut had a drinking problem, possibly even worse than U.S. Grant. He was removed from command in September 1861, and returned to Belvidere Illinois in disgrace.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General William T. Sherman “expressed himself too freely” while in command of the Department of the Cumberland in Kentucky (and may have suffered a nervous breakdown.) He was removed from command, Don Carlos Buell took over the renamed “Department of the Ohio,” and Sherman disappeared for a while. Then, Henry Halleck arrived from California, was made Major General, and replaced Fremont (and Hunter) in command in renamed “Department of the Missouri.” Halleck rescued his friend, William Sherman, from obscurity, deposited him in the Camp of Instruction at Benton Barracks near St. Louis in November 1861, and set about rehabilitating Sherman’s career. Sherman encouraged Halleck to do a similar good turn for Stephen Hurlbut; General Hurlbut was recalled from Belvidere, deposited in the Camp of Instruction at Benton Barracks… and dried out from alcohol abuse. In February 1862 both William T. Sherman and his friend, Stephen Hurlbut, returned to service. And supported each other at the April 6th Battle of Shiloh.

Had it not been for the Second Seminole War, Sherman and Hurlbut would likely never have met…

http://shilohdiscussiongroup.com/topic/1660-stephen-a-hurlbut/

The Civil War required officers to grasp war above the tactical level in order to win it. The Operational Level and the Strategic Level. For all of them, learning the regiment, then the brigade. Putting together the division in the fight, and then the corps. This took all of 1862 for those who rose to corps level to master. Earlier Indian war experience was nothing like this, and there were few troop leading skills practiced above the platoon and company and regiment that these officers learned in Florida as lieutenants useful in the eastern theater and western theater. Maybe Missouri had some similarity to Indian warfare. I would say the Seminole war was more of what we call today counter-insurgency, and not at all what we call high-intensity of large scale traditional European warfare.

Well of course! Captain Gabriel J. Rains tested his explosive devices out on the Seminoles near Fort King in 1840. Which caused the Indians to retaliate and shot Rains in the lung, which took him over a year to convalesce from the injury. Later in the 1876 Rains applied to the federal government for a pension due to the injury in combat he received in 1840. He was given a job at the quartermaster depot, which was the closest thing to a pension at the time. I tell this story in my book, “Alachua Ambush.”

Its Ight