Gettysburg Off the Beaten Path: The Bliss Farm

Just like many farms on the Gettysburg Battlefield, the roughly 60-acre farm of William and Adeline Bliss lay in the no-mans land of the Gettysburg battlefield, and in the midst of the battle, the Bliss barn and home were deliberately set ablaze.* Making the farmstead a battle casualty in its own right.

Situated south of the town and on the west side of the Emmittsburg Road, the Bliss Farm witnessed some of the most intense small unit fighting at Gettysburg. The farm and its buildings and outbuildings may have changed hands as many as ten times over the course of July 2nd and 3rd. In 1856 the farm was described as having, “a double log and frame house, weather-boarded, 2 wells…with pumps–a variety of fruit in the orchards include peaches and cherries.” By the time of the battle, a Pennsylvania bank barn had been added to the property. “Mr. Bliss was like many other [Pennsylvania] farmers,” claimed Charles Paige of the 14th Connecticut, “who give more attention to the architecture and pretentiousness of their barns than they do their houses…”

Tragedy seemed to follow William Bliss. He was the youngest of eleven children born to Doctor James and Hannah Guild Bliss. When William was 17, his mother Hannah died suddenly. He lost his father in 1835, and three of the six children born to William and Adeline died at an early age.

William and Adeline persevered, moving from place-to-place—Bradford County, Pennsylvania, Chautauqua County New York—and then in 1857 to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. At the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, William was 63 years old and living on the farm with his wife and two of their three children—Sarah and Frances.

By late mid-morning of July 1st, some of the Union 1st Corps troops were trekking cross country near the Bliss Farm, destined for Seminary and McPherson Ridges northwest of the Bliss Farm. According to one account, news of the battle (outside of the obvious sounds of battle rumbling a few miles to the north), came from Laura and Carrie McMillian. The McMillian’s lived just to the north of the Bliss family, and the McMillian ladies had provided Federal troops with water as their father took his ax and helped to fell his fences to allow the Union soldiers unimpeded access across his land.

Frances and Sarah Bliss set off with Laura and Carrie McMillen to the Jacob Weikert farm, “to the east back of the round tops,” and helped to make bread for the next few days and to assist the wounded. At some point William and Adeline also fled the farm, in doing so “they left the doors open, the table set, the beds were made, apparently nothing had been taken out at all,” including their impressive library.

By the morning of July 2nd, the Army of the Potomac had established their main line of battle 650 yards to the east of the Bliss Farm along Cemetery Ridge. Meantime, the Confederates, too, were establishing their line of battle 550 yards to the west along Seminary Ridge. The five South Carolina regiments of Col. William L. J. Lowrance’s brigade held the Confederate right flank on the morning of the second day of the battle. Lowrance, “threw out a strong line, of skirmishers extending fully one half mile to the right, including to the rear.”

The Federal 2nd Corps also dispatched skirmishers to the front. The portion of the Union line facing the Bliss Farm was manned by the 3,643 men of the 3rd Division of the 2nd Corps. The division was commanded by the hard fighting, and allegedly hard-drinking, Brig. Gen. Alexander “Fighting Elleck” Hays. Hays was a West Point graduate of the class of 1844 and a veteran of the Mexican War, and of the old army. Elements of the 111th and 125th New York Regiments along with the 1st Delaware were deployed on the Federal skirmish line. The battle between the Union and Confederate skirmish lines “to and fro,” throughout the late morning and early afternoon. Soon the 39th New York “Garibaldi Guard” were on the skirmish line near the Bliss Farm, which Hays referred to as that “damned white house.” The New Yorkers wavered and began to give way, which led to Hays tearing across the fields on his horse into the no man’s land to take charge of the situation, and to encourage the men. “It was the first and last time I ever saw a division commander with flag and staff on the skirmish line,” recalled Col. Clinton McDougall. Four companies of the 4th Ohio, and Company B of the 106th Pennsylvania, too, took to the fields in support of the embattled skirmishers vying for the Bliss Farm. North of the 2nd Corps skirmish line, the 11th Corps skirmish line was also active, battling Confederates throughout the day in along Smith’s Ridge and Long Lane (it was in this action that George Nixon of the 73rd Ohio was mortally wounded. Nixon was the great grandfather of President Richard M. Nixon).

As the day wore on, the South Carolinians were replaced by Brig. Gen. Carnot Posey and his all Mississippi brigade. Posey was not to be outdone by Hays’ Federals. The Magnolia State general initially pressed the 16th and 19th Mississippi regiments forward toward the Bliss buildings. As the day wore on, Posey committed as many as 1,000 more soldiers from the 16th, 19th, & 48th Mississippi regiments to the battle at the Bliss Farm. The Bliss Farm was quickly developing into a grudge match between Hays and Posey, and their respective skirmishers. Rather than waiting for the main Confederate attack to unfold and drive back Hays men with overwhelming force, as John Bell Hood had done to the Maj. Homer Stoughton’s United States Sharpshooters during the assault on Little Round Top and Devil’s Den, Posey was committing crucial manpower to an unimportant farmstead.

By midafternoon Company I of the 12th New Jersey and the 1st Delaware were manning the fenceline near the Bliss barn, and the Confederate assault on the Union left and center was underway. Posey’s men succeeded in routing the 1st Delaware. “Looking around I saw the men of the 1st Delaware running to the rear, recalled Sgt. Henry Bowen of the 12th New Jersey, “soon catching up with Lieut. Col. [Edward P.] Harris who was getting to the rear as fast as he could, he swung his sword around, called me a hard name, telling me to go back, this I did not do but made a detour around him and got across…in record time” Harris was soon placed under arrest by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, and the Bliss Farm was once again under Confederate control, and four companies of the 12th New Jersey were tasked with taking back control of the farm buildings. The Garden State men managed to take a number of prisoners, but with more fighting and maneuvering to the north and south of the farm, their position was untenable. The July 2nd fight at the Bliss Farm, and the overzealous want on Carnot Posey’s part to engage nearly three-quarters of his manpower with taking and holding this nonvital complex cost Lee and his army. As Longstreet’s July 2nd assault rolled from south to north, only one of Posey’s regiments strode toward Cemetery Ridge in support of the brigade to their right, that of Brig. Ambrose Wright. Wright’s four Georgia regiments succeeded in puncturing the Union center. The next day, Wright claimed that getting to Cemetery Ridge was the easy part, staying there was the hard part.

The battle for the Bliss Farm was renewed on July 3rd. The 12th Mississippi took a position in and around the farm buildings and harrassed Hays Federals with fire throughout the morning. Five companies of the 12th New Jersey sprinted across the open fields toward the Bliss Farm, only to find that the Confederates slipped quietly away to a nearby orchard, renewing their harassing fire. Four undersized companies of the 14th Connecticut now joined the fray. Federals were falling left and right in repeated attempts to take the farm. Enough was enough for Hays and brigade commander Thomas Smyth (Smyth has the sad distinction of being the last Union general killed in combat during the war). Authorization to fire the house and barn was given by both officers. Smyth authorized Lt. Frederick Seymour of Company I, 14th Connecticut to burn the structures if “the rebs make it so hot,” that the Federals couldn’t hold the farm. Seymour was wounded on his way to the front and never delivered the order. Meantime, Hays sent Sgt. Charles Hitchcock of the 111th New York to the front with orders to burn the farm. Minutes later the buildings were ablaze, as the Federals used hay, straw, and paper from cartridges as a propellant. The battle for the Bliss Farm was over, and tragedy once more played out in the life of William Bliss.

After the battle, Bliss submitted two separate compensation claims to the government for damages to his property in the amount of $3,256.05. He was never paid for the loss of his farm by the U.S. government. In October of 1865, Bliss sold his land to his neighbor Nicholas Codori for $1,000. The Bliss family left Gettysburg and once again settled in Chautauqua County New York. William Bliss died on August 18, 1888, and allegedly said of his farm “Let it go; if I had twenty farms I would given them all for such a victory.”

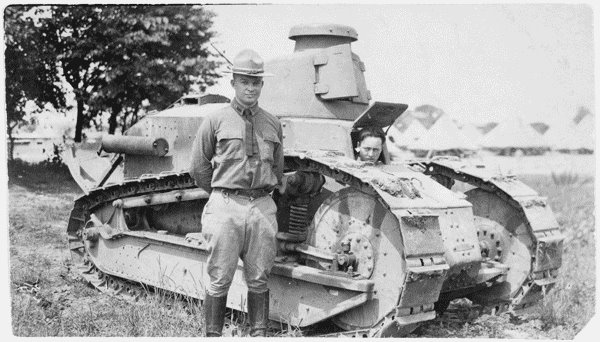

The United States military returned to the fields that once house the Bliss Farm during the twentieth century. Rather than Yankees and Rebels struggling over the Bliss barn, it was a Renault FT-17 tank. The Bliss Farm was used as a training site for United States soldiers during World War I. Camp Colt, was one of two training camps at Gettysburg during 1917-1918. Camp Colt was created in March of 1918, as the training facility for the newly formed United States Tank Corps. The camp’s commanding officer was Capt. Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower trained more than 10,000 tankers for operations in Europe. At its peak, the camp housed some 6,400 men at one time. On June 6, 1918, the first and only tank arrived at Camp Colt. The new tankers drove the tank through the streets of Gettysburg, and then onto the 1863 battlefield, using the old bank of the barn and the cellar of the house as tank obstacles. The barn in 1863 was, “75 feet long and 33 feet wide,” and the old bank mound was an inviting obstacle to run over with the nearly 7-ton tank.

Camp Colt was disbanded with the end of World War I, but this would not be the last time that the military used the battlefield for military installations or exercises. In 1922, a detachment of the United States Marine Corps marched to Gettysburg and reenacted the battle. Their reenactment included 75mm howitzers, bombers (some of which were landed on the Bliss Farm), smoke screens, observation balloons, and more.

During World War II, a German POW camp was situated along the Emmittsburg Road near the former site of the Bliss Farm, and Camp Sharpe was established in McMillen Woods (today the Scout campground), to train “soldiers for psychological operations.”

Author Note:

The Bliss Farm was described by one soldier as:

“[A] large barn almost a citadel in itself, It was expensively and elaborately built structure…75 feet long and 33 feet wide…[its] basement 10 feet high constructed of stone, and its upper part, 16 feet to the eaves…There was an overhang 10 feet long…There was 5 doors in the front wall of the basement and 3 windows in each end…Ninety paces north of [the barn] was the mansion, a frame building, two stories in height. As it had a front of three rooms width and two front doors, and there now remain two cellar excavations…”

For more information about the battle for the Bliss Farm, see John M. Archer’s excellent book Fury on the Bliss Farm at Gettysburg.

*The barn of John Herbst was also burned during the battle, as was the Emanual Harmon farm, and the Joseph Sherfy barn.

To Reach the Site of the Bliss Farm:

From the town square.

-Drive two blocks south on Baltimore Street.

-Turn right onto West Middle Street.

-Follow West Middle Street for 0.7 miles (which becomes the Fairfield Road).

-Turn left onto West Confederate Ave.

-Follow West Confederate Ave. for 0.8 miles and park at the North Carolina Memorial.

-Exit your vehicle and walk straight out from the North Carolina Memorial for 515 yards. You will see a mound of earth and a few Union monuments and a house marker.

I haven’t been to Gettysburg for a number of years. Thanks so much for the incredible detail of the Bliss Farm and other sites over the last few days! I am looking forward to attending the Symposium in August.

The 125th NYVI (the third Troy regiment), with the 126th, the 111th and companies of the 39th NYVI fought together throughout the three days. The 125th is dear to the hearts of Civil War students in Troy and West Troy (now Watervliet) NY. Thanks for describing a part of their Gettysburg action not so regularly reported as their participation in the First Day Fight at Plum Run (where they lost their Colonel) and their role in repelling the charge of Pickett/Pettigrew/Trimble on the Third Day.

I saw the tank, and just figured that, in the past, when the National Park Service told people not to park on the grass at Gettysburg—-they meant it.

Hi Chris

There is a town of Bliss in

Wyoming coumty N.Y.

. I was under the impression he was from there originally. ?

Thank you for a great series

Look forward to them all

Oops with a k not c sorry

Hiking to the Bliss farm site is well worth it for the views of the Union line and the terrain ( presuming it was not altered drastically for WW I training). I parked near Long Lane, which is nearly on a line with the Bliss site, and walked south. I do not know if that alternative remains possible. Too bad GNMP cannot install a more visible marker that would enhance visibility from W. Confederate or Hancock Blvds.

Co. F of the 12th Virginia, Mahone’s Brigade ANV was involved in the fight on July 2. Horn, The Petersburg Regiment (Savas Beatie, 2019) (179-181.