Army Posts Since 1860

The names of U.S. Army posts are in the news of late. In an effort to inform the debate, here is some information about how the names and current situation came about, as expressed in three maps.

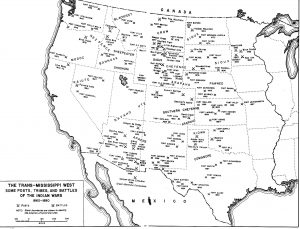

The first map shows the extensive post-Civil War network of posts established during the Indian Wars period from 1860 to 1890. Many posts were named for Union war heroes or war dead, such as Phil Kearny, Grant, Sheridan, Harker, Sill, D.A. Russell, and many others. (Fort Meade on this map is why the post in Maryland today is Fort George G. Meade, to avoid confusion.) This trend extended to Schofield Barracks and Fort DeRussy in Hawaii, plus the former Camp John Hay and Fort McKinley in the Philippines. Many of the western forts fell into disuse in the early 20th Century, and quite a few are preserved as national or state parks.

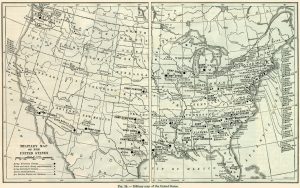

The second map shows U.S. Army installations 1917-1919, during the World War I years. While the Army had a network of smaller posts around the country, note how many frontier posts have closed or fallen into reduced roles at this time. Large bases were set up to accommodate the massive influx of soldiers training for service in Europe, as the Army expanded from 400,000 to over 4 million by war’s end. Many posts still active today were founded at this time as training installations. These new installations were named for local military figures of renown (Grant, Funston, Custer, Benning, Bragg, Pike, Devens, etc). Several posts (Wadsworth, McClellan, Logan, etc) were built by northern National Guard troops shipped south to train in a supposedly more temperate climate. Some of these places closed after the war, or reverted to state control, while others stayed in Army possession for future use.

The third map, an interactive located here, shows the Army’s active installations today. The difference between this map and the previous map is largely explained with the post-Cold War drawdown, specifically, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) rounds from 1989 to 2005. Many northern bases were closed and functions consolidated in areas closer to the southern border and the coasts. A side effect is that the Army has retreated somewhat from major population centers, especially in places like New York City (closure of Governor’s Island/First Army HQ), San Francisco (ex-Presidio), Chicago (ex-Fort Sheridan) and Atlanta (ex-Fort McPherson), among other places.

So, to summarize: Western forts were named to recognize Union leaders of the Civil War. During World War I, large bases received names of local significance, either to the communities or the units stationed there. Force changes and drawdowns have since concentrated many active Army bases in the former Confederacy.

Of course, there are exceptions to the general trends laid out above. For our purposes, three that stand out are Fort Hood in Texas, Fort Polk in Louisiana, and Camp Forrest in Tennessee. Fort Hood was founded in 1942 as the Tank Destroyer School; its first commander, Andrew Bruce, named it in honor of General J.B. Hood because of Hood’s connection to the Texas Brigade. Fort Polk grew out of the 1941 Louisiana Maneuver Area, and was named for Leonidas Polk because of his ties to the state (Polk was the Episcopal bishop of New Orleans). The Army turned over Camp Forrest (named for Nathan B. Forrest, who grew up nearby) to the Air Force, which now operates the installation as Arnold Air Force Base, in honor of General of the Air Force H.H. “Hap” Arnold.

I hope this adds perspective on how the roll of Army installations got to its present state after 160 years of evolution.

Thanks for the clarity on U.S. Army installation names. As regards the Navy, luckily ships do not endure much beyond thirty years, otherwise there would be calls to rename USS Robert E. Lee, USS Stonewall Jackson, USS Beauregard…

I’m someone who feels that certain aspects of the Confederacy deserve to be remembered with respect. I’m also one who doesn’t want to see wholesale changes in American culture made under mob pressure, or to score cheap political points.

But I’m not ready to “die on the hill” of naming Army bases. Even I admit that the current proportion of base names, Union to Confederate, is way out of whack. When you look at the current “major” Army bases—bases that house deployable commands (e.g., 1st Cavalry Division) or major service schools, five are named for prominent Confederate generals—-Lee, Bragg, Polk, Hood and Gordon. Only two are named for prominent Union generals—-Meade, McClellan. And the Union won the war!

Chris’ article does a good job of explaining how we got to that naming imbalance: originally, we HAD plenty of bases named for Union generals, but we closed them over the years.

Personally, I think this is silly, and a non-issue. But reasonable people can disagree. And the Civil War ended over 150 years ago. The percentage of Americans who have emotional ties to the legacy of the Confederacy—-largely because we have ancestors who fought for it—is diminishing. There are many people whose families have lived in the South for over a century—but those families arrived in the early 1900s. Decades after the war ended.

In life, you have to pick your battles. The naming of Army bases is not a battle I’m going to pick. Perhaps, if the Republicans relent on Army base names, the Democrats won’t pull down all the Confederate statues at national parks.

Great info Chris. Agree much with Don’s reply as well. The political landscape has been gravitating down this path for awhile now, lock step with the transmutation of American history from the academia-activist cudgel.

A very thoughtful comment so thanks. I think it would e appropriate to rename army posts in the names of deceased MOH winners. That way, the stories could be told and it might be instructional. If the Republicans give in I just hope it’s for the right reasons and not because a mob says so.

Bruce, thanks for the kind words.

They would be tearing down their own statues on multiple fronts. Remember the democrats were the south, Jim Crow and the other past evils like the KKK. If you read Wikipedia’s version of George C. Wallace, you would be shocked. Sounds like a nice guy the way they sugar coat it. In addition, those military bases were closed in the 1990s, by Bill Clinton, again a democrat. The full scale closing of those bases, destroyed a number of cities, Montgomery, Alabama, is a great example. I’m in agreement with renaming bases but I would like to see one named after 20th Century Generals, like Patton.

Living in Hawaii, there are a huge number of “named” army and air force installations. The greater number being named coast artillery batteries, and “forts” associated with CAC troops that manned the batteries. These batteries were constructed in the early 20th century not long after Hawaii achieved territorial status. Most all the names were from officers in the CAC, exception being Fort Kamehameha being named for the Hawaiian alii/king (Ft Kam is now part of Joint Base Pearl Harbor Hickam). Our major installations are Schofield Barracks (25th Inf Div) (Schofield has significance to Hawaii not related to his civil war history), Ft Shafter (HQ US Army Pacific) — Shafter was a Span-Am war general, Wheeler AAF (25th Combat Aviation Bde) named for a pilot, not that Wheeler, and Tripler medical center (Tripler was a civil war union medical officer).

Although this is off-topic for a serious issue, I can’t resist pointing out a personal connection to the World War I vintage map. When, a long time ago, I reported to Fort Gordon for AIT (MOS 95B) I had no idea that it occupied the area of what used to be Camp Hancock, (near Augusta), and the original Camp Gordon was elsewhere in Georgia.

OK, this has absolutely nothing to do with the subject of this article (my apologies to you Chris K.), but I thought it was pretty cool, and it ties in with baseball starting up over the past few days. I didn’t know where else to post it on the ECW site, and I don’t have the time right now to try to construct a possible article that would hopefully be published on here. I hope everyone enjoys this as much as I did..

https://ghostsofdc.org/2012/05/10/abner-doubleday-arlington-cemetary-1939/

Although Abner Doubleday’s connection to Baseball is tenuous, the intertwining of Baseball with the American Civil War is not. Union soldiers eventually pushed the development of the New York version of the game over the Massachusetts version. And along the way, Baseball killed Cricket in America (Cricket is played in UK and the former British Commonwealth nations.) By the end of the war, Baseball was played by soldiers, North and South.

As for Abner Doubleday: his letters from Fort Sumter in 1860-61 were passed along from his father to President-elect Abraham Lincoln, providing Lincoln with the true state of affairs in Charleston Harbor.

Thanks to Douglas Pauly for providing a ray of sunshine in this turbulent time…

Does anyone have any info on a Fort Bell? I found a badge from my dad that indicates he was in the US Army Signal Corp, Fort Bell Engr Dept. I’m guessing early 40’s?