The Book I Threw (And Then Picked Up Again)

The first book I ever threw across a room? The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane. (Assigned reading in high school literature class.) That afternoon started a little journey of reality and history…I just didn’t know it when I pitched the book.

The first book I ever threw across a room? The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane. (Assigned reading in high school literature class.) That afternoon started a little journey of reality and history…I just didn’t know it when I pitched the book.

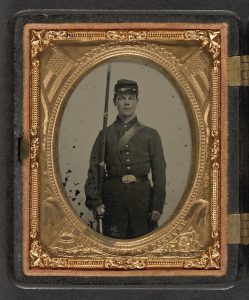

Henry Fleming—the fictional young soldier in a fictional Union regiment in the Battle of Chancellorsville—irritated me to no end when I first read the book as a teenager. Fleming did not fit my ideal of a Civil War soldier. He was a coward. He had no religious faith. And then spent half the book rationalizing his flight from the battle lines and his regimental comrades. The Civil War soldiers I had read about were all perfectly brave. The story was just a story, and it did not fit with how I thought battle happened for a soldier, so after I finished the class work, I promptly pitched the story from my mind. That book was just about a confused soldier who ran away and badly represented real guys in blue or gray.

Or was it? Fast-forward. I read a lot more history books and primary sources and started getting an idea that battle was a fearful, confused experience for most Civil War soldiers. They did not understand a fight with the details that researchers and arm-chair historians enjoy. A soldier did not experience battle with his regiment as nice, orderly little lines on a map. But it took me an embarrassingly long time to understand that.

The Red Badge of Courage came up in an ECW conversation one year at the symposium. I gave an inward shudder at the title, but then almost fell off my chair when Chris Mackowski started talking about how he appreciated the novel and its battle descriptions. Something must be wrong! Either we did not read the same book or I must have really missed something. Intrigued, I decided to revisit the story.

Ten years after I threw the book across the room, I opened another copy and felt like I was reading it for the first time. No, Henry Fleming will never be my favorite literary character (I feel pretty safe writing that), but the story of the common soldier and the confusion of battle came through the pages so clearly and matched words or episodes from primary sources. It was a piece of literary brilliance and it had historical backing.

Stephen Crane published The Red Badge of Courage in serialized form in 1894 and as a novel the following year. Born in 1871, he had no first hand experience of the Civil War or even combat. However, he listened to stories from Civil War veterans which most critics believe influenced his war novel. By stripping away the need to wonder if the regiment was real and if the details were one hundred percent accurate, Crane lets the reader focus on “The Youth” (Henry Fleming) and his handful of comrades in a company in a very green regiment. It’s not a history of the Chancellorsville Campaign or a regimental history. The novel becomes a study in the feelings and emotions of war, from questioning, fears, self-preservation, shame, and conviction toward redemption, acceptance, courage, passion, patriotism, and self-realization.

While it should be noted that many Civil War soldiers did not run away from their regiment in battle like Private Fleming, their letters and journals reflect the range of feelings and even statements like “I would run if I could.” Desertion or cowardice was handled severely if the soldier was caught; execution, hard labor, drumming out of the regiment, or other creative punishments could follow, depending on the unit and the commanding officers. Sometimes fear of losing reputation among comrades or the rumors that would get back to a hometown was enough to keep a soldier in the ranks. Other times, the patriotic ideas or “band of brothers” comradeship held a soldier to his post of duty.

The micro-details of history woven into the story give a color and authentic feel, again reflective of the real soldiers’ lives in camp, on the march, in battle, and recovering in the aftermath of a fight. The descriptions of the “snap-shots” of the battle scenes also challenge a reader to ponder what privates saw in the battle smoke. For example:

In another direction he saw a magnificent brigade going with the evident intention of driving the enemy from a wood. They passed in out of sight and presently there was a most awe-inspiring racket in the wood. The noise was unspeakable. Having stirred this prodigious uproar, and, apparently finding it too prodigious, the brigade, after a little time, came marching airily out again with its fine formation in nowise disturbed. There were no traces of speed in its movements. The brigade was jaunty and seemed to point a proud thumb at the yelling wood.

On a slope to the left there was a long row of guns, gruff and maddened, denouncing the enemy, who, down the woods, were forming for another attack in the pitiless monotony of conflicts. The round red discharges from the guns made a crimson flare and a high, thick smoke. Occasional glimpses could be caught of groups of toiling artillerymen. In the rear of this row of guns stood a house, calm and white, amid bursting shells. A congregation of horses, tied to a long railing, were tugging frenziedly at their bridles. Men were running hither and thither.

The detached battle between the four regiments lasted for some time. There chanced to no interference, and they settled their dispute by themselves. They struck savagely and powerfully at each other for a period of minutes, and the lighter-hued regiments faltered an drew back, leaving the dark-blue lines shouting. The youth could see the two flags shaking with laughter amid the smoke remnant.

So why did I hate this book for ten years and think of it only as the book I’d thrown across the room? Looking back, I find Henry Fleming as the example of my own “misconduct.” Like “The Youth,” I wanted war to be glorious and that’s the way I thought it was when I was in my teens. Similar to Henry’s flight and discovery of the red road with staggering wounded, a post-college study on Gettysburg field hospitals shattered that idea of glorious war for me. Later and hundreds of research pages further, the idea of an orderly battle experience for the common soldier was swept away. That next time I picked up the story to re-read it, my notions about what I thought the Civil War was had already been dismantled and I could appreciate the literary journey and concept of combat emotion and limited point of view which is ultimately mirroring the experiences of real soldiers.

I have to confess. I’ve spent the summer of 2020 engrossed in studying The Red Badge of Courage, and it’s been an interesting season to approach the story for a third time. Already prepared to appreciate the story, I was able to look closer at what the author accomplished and how the tale can be a powerful teaching point and discussion starter for topics like Civil War medicine, battle for the common soldier, and the Chancellorsville Campaign.

While it’s been an enjoyable literary and historical experience, it’s also been a positive reminder that it can be helpful to go back and re-look at the books or situations we thought we hated. Does a deeper understanding grow an appreciation? Or at minimum give a more nuanced perspective? I find myself challenged to be less quick to judge, more open to listening and learning, and then making informed theories or thought positions.

Thankfully, an ECW colleague unknowingly pushed me to re-read The Red Badge of Courage, allowing me to revise my opinion formed in my high-school “wisdom.” Have you experienced something like this in your history journeys? Finding that notions change as time and research goes on. Was it a good feeling? Slightly regretful? Or a “break-through” moment for you?

(P.S. And if you’re wondering why I spent the summer with The Red Badge of Courage.… It’s for work!)

(P.S. And if you’re wondering why I spent the summer with The Red Badge of Courage.… It’s for work!)

Central Virginia Battlefields Trust is hosting a Virtual Fundraiser and Gala this month to raise $10,000 for battlefield preservation. Guess what the event theme is? Yep. Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage and the Chancellorsville Campaign. Come over and join the online party on the Facebook Event Page with daily historical questions and more in the discussion section. There’s more information on the lower-half of the event home page, including details about the free, virtual gala this weekend which includes a tour with Chris Mackowski, a preservation chat, presentation about Civil War soldiers, and more!

In the movie, “Red Badge of Courage”, Henry Fleming was played by a real hero, Audie Murphy. Audie was a Medal of Honor recipient. I understand that the director had a hard time talking him into running away in that famous scene. Even though it was just a movie, it was difficult for him to abandon his duty.

Crane’s RBOC was the book that began my interest in the Civil War. It holds up remarkably well. For another pioneering iconoclast view in historical fiction, I recommend Kenneth Roberts’s Oliver Wiswell, the story of a Britsh American Loyalist in the American Revolution. It was written in 1940 so you can imagine it was a groundbreaking and controversial book in its day.

Wonderful thoughts on this book, Sarah. I hope to have a similar new experience one day when I revisit Wuthering Heights — a book I hated on first read. 😉

You must try it again! One of my favorites. Try listening to it. You’ll be hooked!

Okay, thanks!

Richard Thomas starred in a 1974 remake of Red Badge. While enjoyable, it is no equal to the book in its poignant depiction of war.

Historian Lesley Gordon has done much work in the area of battlefield experience. “I Never Was a Coward” is an excellent addition to one’s library. I have been working on the allegations of cowardice lobbed at the 11th NY at 1st Bull Run–she has been quite an inspiration to me.

“A Broken Regiment” is her book on the Connecticut troops–

Yes, I have experienced that. So, I’ll talk non-Civil War for a minute. I am fascinated by the Titanic tragedy. I adored the movie first (who wouldn’t love Leo’s portrayal of Jack??), then I dabbled into some casual study of the ship, the sinking, etc. I went to exhibits and even bought a tea set with the 3rd class china pattern. However, last year, I endeavored to write a historical fiction book set on the Titanic, so I totally gave myself over to analyzing every inch of the ship. I read more books, I really sank my teeth into who the people were, their stories, the culture surrounding the era, who the ship was built (something I looked over before), and everything in between. After a while, I could walk the deck plans in my sleep. But then, I watched the movie again and my eyes were never dry for a minute. What had changed? I didn’t just “know what happened”. I understood, I empathized, I could put myself on the decks or in the lifeboats because I had read the survivor accounts and KNOW what happened. It was a much more powerful experience to watch the film, then visit the museum in Pigeon Forge (for the third time) and see the artifacts. I was angry that people were just skimming through the displays and so focused on getting to the gift shop that they didn’t let the history really sink in. So, digging deeper into the true and FULL history of the tragedy gave me a better appreciation of the events, but it ruined me at the same time. I felt so much more than I ever expected to feel. I’ll never be able to look at it the same way. I don’t think I could bring myself to drink from that 3rd class teacup again either.

Thank-you for this wonderfully reflective essay. Now, I plan to read the book as well. I must admit that I was drawn into your article by the idea of throwing the book across the room. When I was an English major, years ago, at UC Berkeley, a professor commented that her response upon concluding a Henry James novel was to throw it across the room! I understood her perfectly. Did it really have to end that way? I look forward to reading the Facebook updates.