John Wolcott Phelps’ Emancipation Proclamation

The voyage of the U.S. Frigate Constitution ended at Ship island, a barrier island off the Gulf coast of Mississippi in December, 1861. Prior to disembarking, Brigadier General John Wolcott Phelps gathered all passengers on deck and recited one of the most extraordinary speeches given by any officer during the Civil War. The so-called “Phelps’ Emancipation Proclamation” was not sanctioned army policy and had no authority of law; but the bold statement decrying the institution of slavery as antithetical to free republican government and free labor anticipated President Lincoln’s official proclamation ten months later.

Phelps was careful not to repeat the mistake of General John C. Frémont, who on August 30, 1861 declared that all enslaved people confiscated as the property of rebels would be henceforth forever free. Frémont’s rash action placed Abraham Lincoln in a difficult political situation, as the president attempted to placate both abolitionists and slaveholding Southern Unionists in border states like Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland. Although he endured sharp criticism from his superior, Major General Benjamin Butler, Phelps’s provocative speech was just one of many radical voices pressuring Lincoln for a dramatic shift in war policy.

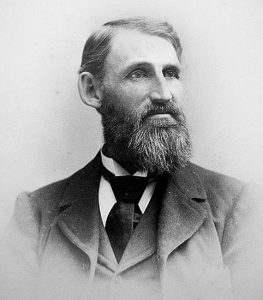

John Wolcott Phelps was a Vermont native and an 1836 West Point graduate who served with distinction in wars against native Creeks and Seminoles in Florida and later took charge of Cherokee removal during the infamous Trail of Tears. Despite his gallant service in the Mexican War, he refused a brevet promotion to captain, feeling he had not yet earned the rank. Years later, Captain Phelps served in operations against filibusterers in Texas and in the Utah expedition against the Mormons. He resigned from service in November, 1859, only to be called back in April 1861 as colonel of the First Vermont Volunteer Infantry. A fellow officer described him as “a tall, middle aged, stooping, awkward looking man,” dressed in a tattered old artillery captain’s uniform replete with disintegrating felt hat and drooping ostrich feather. Despite appearances, Phelps had a well-earned reputation as an outstanding soldier. As his boys marched down Broadway in New York City, a bystander enquired, “Who is that big Vermont colonel?” Another man replied, “Oh that is old Ethan Allen resurrected!”

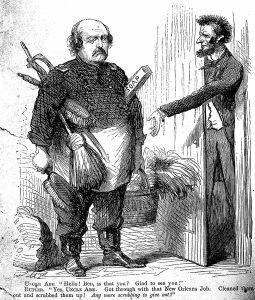

Phelps and his Vermonters landed in Newport News, Virginia, where the old colonel’s talents as a commander drew the attention of General Benjamin Butler. Despite the fact that some regular army officers viewed Phelps as “not in his right mind,” which Butler attributed to his “deep religious enthusiasm upon the subject of slavery,” he recommended Phelps for promotion. Butler entered Phelps’ tent and laid brigadier general shoulder-straps on the table, but the colonel refused to accept them, arguing that his brief service in Newport News was not sufficient cause for such honors. A few months later, Phelps accepted the rank and a key role in the Department of the Gulf. Once Butler got wind of Phelps’ incendiary arrival speech, he realized the depth of his new brigadier’s animus against slavery and the political problems that it presaged.

Addressing his manifesto to “the loyal citizens of the Southwest,”, Phelps made legal, moral, and economic arguments against the evil Institution. He argued that every slave state admitted since the adoption of the Constitution violated that compact and that existing slave states were obliged by honor to abolish the heinous practice. He described slave labor as a monopoly that was inimical to conservative republican principles of free labor and free market competition. Economic rights and opportunity for the European immigrant and the poor Southern tenant farmer alike were “altered to a narrow and belittling despotism” by aristocratic slaveowners. “The time has not yet arrived,” Phelps insisted, “when our southern brethren, for the mere sake of keeping Africans in slavery, will abandon their long cherished free institutions, and enslave themselves.”

“It is the conviction of my command,” Phelps decreed, “as part of the national forces of the United States, that labor—manual labor—is inherently noble; that it cannot be systematically degraded by any nation without ruining its peace, happiness, and power; that free labor is the granite basis on which free institutions must rest; that it is the right, the capital, the inheritance, the hope the poor man everywhere; that it is especially the right of five millions of our fellow-countrymen in the slave states, as well as the four millions of Africans there, and all our efforts, however small or great, whether directed against the interference of governments from abroad, or against rebellious combinations at home, shall be for free labor. Our motto and our standard shall be, here and everywhere, and on all occasions, FREE LABOR AND WORKINGMEN’S RIGHTS. It is on this basis, and this basis alone, that our munificent government, the asylum of the nations, can be perpetuated and preserved.”

Reaction to Phelps’ brash and unexpected proclamation was swift and savage. Despite his own abolitionist leanings, General Butler disavowed it. A naval officer tasked with transporting the proclamation to the mainland ripped it in shreds and tossed it overboard. The Vermont Phoenix attributed Phelps’ “unnecessary and foolish proclamation” to “an erratic tendency” caused by his intense hatred of slavery.

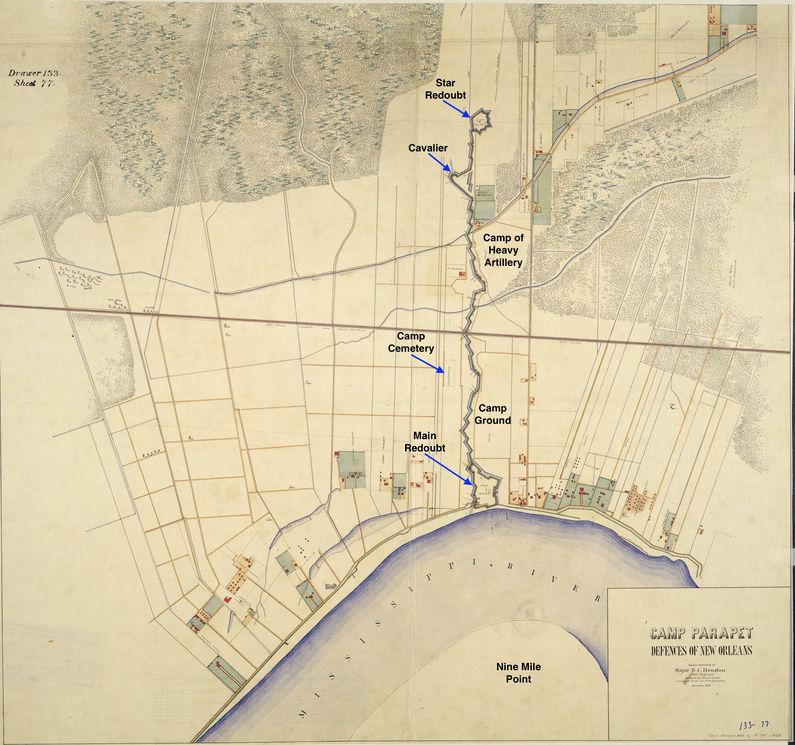

At Camp Parapet near Carrollton, Louisiana, Phelps welcomed throngs of escaped slaves into his care. “Some came loaded with chains and barbarous irons,” he reported. Others were bleeding from shotgun wounds or bore scars from recent whippings. “All complained of the extinction of their moral rights.” By May 1862, large refugee camps had sprouted in many areas where enslaved families could make their escape to Union lines. Butler ordered Phelps to send formerly enslaved refugees to repair a broken levee under the management of two slaveholders, but Phelps pushed back. He only complied after Butler promised that a group of white laborers would augment the work party under the direction of a Union captain.

In the meantime, the refugee crisis grew unsustainable, prompting Butler to order so-called “contrabands” to be excluded from Union lines. One June 16, 1862, Phelps composed a heartfelt and brazen reply, urging the government to reconsider its policy toward these displaced people. Phelps described the refugee situation in elegant and sympathetic prose. The government, Phelps argued, could not secure even “the simplest natural rights” for four million of its peoples, “and if it cannot protect all its subjects, it can protect none, either black or white. It is nearly a hundred years since our people first declared to the nations of the world that all men are born free; and still we have not made our declaration good.” Since Congress had been unable to resolve the sectional crisis over slavery by legal means, resulting in violent civil war, Phelps urged Lincoln to use his wartime powers to declare the abolition of slavery as a necessary measure for public safety.

Butler composed a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. “General Phelps,” Butler wrote, “intends to make this is test case for the policy of the government.” Butler respected Phelps’ principles, “for his whole soul is in it, and he is a good soldier of large experience, and no braver man lives.” Nevertheless, he vowed to honor the president’s wishes regarding the emancipation question.

Lincoln was aware that critics had accused Phelps of extinguishing whatever Union feeling remained in Louisiana through his strong advocacy of abolition. After the disastrous failures of his Peninsular campaign, Lincoln drafted his preliminary emancipation proclamation. Replying to one of his agents in New Orleans a few days later, Lincoln reminded him that it was their own fault that Louisianans were “annoyed by the presence of General Phelps” and warned that unless they resumed their place in the Union, they might look for something even worse than his mere presence.

Six weeks had passed with no reply from Washington to Butler’s missive, so Phelps decided to take matters into his own hands. He sent a short letter to headquarters requesting clothing, arms, and ammunition for three regiments of black soldiers. He further recommended that recent West Point graduates be appointed to command these units. Meanwhile, Butler had sent a memo to Phelps suggesting that he employ his refugees as laborers. Phelps replied that “while I am willing to prepare African regiments for the defense of the government against its assailants, I am not willing to become the mere slave-driver which you propose” and submitted his resignation on August 2, 1862. Butler urged him to reconsider, but Phelps would not budge. “It can be of little consequence to me as to what kind of slavery I am to be subjected,” he retorted, “whether to African slavery or to that which you so offensively propose for me, giving me an order wholly opposed to my convictions of right.”

Had Phelps known that Lincoln had already submitted the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet on July 22, and that the proclamation’s final draft would authorize the enrollment of former slaves in the US Army, he might have been more patient. The Vermont Phoenix later claimed that Governor Frederick Holbrook convinced Lincoln to offer Phelps a major general’s commission and overall command of all US Colored Troops in 1863. As the story goes, Phelps insisted that the commission be made retroactive to his resignation date and the president refused. True or not, Phelps remained at home for the balance of the war.

Phelps was a polymath. In his retirement, he indulged a wide range of interests, including translation and publication of a French pamphlet criticizing secret societies. He was admitted to the Vermont state bar, studied whale fossils and magnetism, wrote a treatise on the 1257 slave manumission in Bologna, and donated his copy of a 1567 Aztec dictionary to a museum in Moscow. In 1867, he joined the National Christian Association, a group dedicated to various moral reforms, including temperance, bibles in public schools and opposition to secret societies, tobacco, animal cruelty, and socialism. His Quixotic postwar life culminated in a nomination for US president on the association’s American Party ticket in 1880.

Phelps reasoned that the best way “to restore a healthy union” between North and South in the wake of the Civil War was to “unite in common opposition to the Masonic lodge.” It was an odd platform to say the least. American, Greenback, and Prohibition candidates were merely a side show to the main contest between Republican James Garfield and Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. All five national candidates were former Union generals. Phelps finished last with a paltry 707 votes.

In his twilight years the old bachelor finally married and at age 70 fathered his only child. On February 2, 1885, 72-year-old Phelps was seen shoveling snow in his shirtsleeves. The next morning, neighbors noticed he was not engaged in his usual pre-dawn routine of sawing wood. His wife found him dead next to a well-thumbed copy of the New Testament in the original Greek.

Phelps’ eulogists tried to balance their admiration for his remarkable intellect, steadfastness, and rectitude with his idiosyncrasies and blunt moral righteousness. “He was not always fully understood even by those who knew him well,” claimed Rev. William H. Collins at the memorial service. Major General Rush C. Hawkins said, “I have never known a man so free from the hypocrisies, sins, and vices which make humanity despicable as was John W. Phelps.”

Phelps was one of a small minority of Union Army general officers who were outspoken abolitionists. A correspondent of the London Times who visited him in camp reported that Phelps had returned to the army in 1861 with one purpose: to destroy slavery; a man “who places old John Brown on a level with the great martyrs of the Christian world.” Together with Radical Republican politicians, religious leaders, and crusading journalists, Phelps was among a handful of Union generals like John C. Frémont and David Hunter who pushed the boundaries of their authority, prodding Lincoln to transform a war to save the Union into a war of slave liberation.

David T. Dixon is the author of Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (University of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Sources:

McClaughry, John. “John Wolcott Phelps: The Civil War General Who Became a Forgotten Presidential Candidate in 1880.” Vermont History 38 (Autumn 1970): 263—90.

Messner, William F. “General John Wolcott Phelps and Conservative Reform in Nineteenth Century America.” Vermont History 53 (Winter 1985): 17—35.

Taylor, Amy Murrell. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Abraham Lincoln to Reverdy Johnson, July 26, 1862. Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

It is probably due the New Orleans Campaign, forcing the Mouth of the Mississippi and subsequent assault on Forts Jackson and St. Philip, being recognized as a NAVAL operation commanded by Flag Officer Farragut that the importance of Ship Island is ignored. A pity, because the assembly there of 14,000 Union soldiers, most of whom were from New England, is what brought Eastern soldiers to the Western Theater.

Thanks to David T. Dixon for expanding the story of John Phelps (a fascinating man whose story tends to get lost after the conquest of New Orleans.) And for reminding us “Politics is just as important to War as actual fighting.”

Excellent article. I know there are pockets of his writings in collections around the country, I can remember seeing them years ago for sale on an auction site along with the occasional letter. It would be interesting to follow his career from Florida to the West. I would like to know how his time displacing Native peoples informed his Abolitionist convictions (if they did). Kind of difficult to reconcile these two things.