What We’ve Learned: Pondering Usable History

If but for a missing license plate, state police might not have caught Timothy McVeigh, or at least not soon after the crime. At 9:02 a.m. on April 19, 1995, McVeigh blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. Ninety minutes later, an Oklahoma State Trooper pulled McVeigh over for driving without a license plate. The trooper found a concealed weapon and arrested McVeigh—without even realizing he’d captured the nation’s public enemy #1, before anyone even knew McVeigh was public enemy #1.

In a museum now standing at the site of the Murrah Building, the infamous 1977 Mercury Marquis with the missing license serves as the centerpiece artifact in a gallery that recounts the story of McVeigh’s capture.

By this point in my visit, I was nearly overwhelmed by the museum’s emotional weight, piled on by an intimately immersive experience and heartbreaking exhibits. Even as I reeled from the story of the attack itself, there was no time to grieve—and I wanted to—as the museum guided me right into the investigation. After all, there had been no time to lose.

And there was McVeigh’s Mercury Marquis. And opposite, there was McVeigh’s mug shot. And there was Abraham Lincoln.

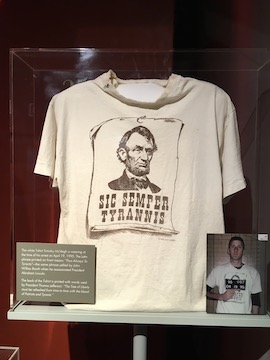

The t-shirt McVeigh was wearing at the time of his arrest—now on display—featured an image of Lincoln along with the words shouted by John Wilkes Booth during Booth’s escape from Ford’s Theater: “sic semper tyrannis.” The back of the shirt, not visible, featured a quote from Jefferson: “The Tree of Liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of Patriots and Tyrants.” I noticed that it did not say anything about innocent victims. Or children.

As McVeigh himself indicated, both quotes have become popular slogans for far-right militants and activists, although I prefer the term coined by journalists Dan Herbeck and Lou Michel as the title of their book about the bombing: “American Terrorist.”

I feel compelled to point out, lest anyone accept it as “doctrine” from the Founding Fathers, that Jefferson’s comment was his individual opinion and not anything enshrined in any of the founding documents. It’s also important to point out that Jefferson made his comment during his rosiest optimism about the French Revolution, which he later admitted was a big mistake. “Your prophecies [about the French Revolution] . . . proved truer than mine,” he admitted to his longtime friend and political rival, John Adams, who had condemned it with dire warnings, yet still “fell short” in his predictions. “[F]or instead of a million,” Jefferson conceded, “the destruction of 8. or 10. millions of human beings has probably been the effect of these convulsions. I did not . . . believe they would have lasted so long, nor have cost so much blood.”

The Booth quote, which was and remains the Virginia state motto, also gets a lot of play in certain circles today. But who gets to decide who’s a tyrant? Lincoln was not universally loved in his day, but he DID get reelected by a convincing margin. Today, he still has his detractors, but he’s become a figure who’s as close to universally loved as anyone in American history.

But not by everyone, as Booth tragically illustrated. McVeigh and his ilk have likewise found a way to plumb history and come up with some things that served their needs.

It reminded me that we’re all looking for ways to look back at history for lessons we can then apply today. The term for his is “usable history”: how can we use history in a way that serves us today.

On one level, this is the implied purpose for the study of history. As I say to roundtables when I’m out on the lecture circuit, Emerging Civil War seeks to connect people to what we see as America’s defining event because, if we lose touch with our own history, we fail to learn the lessons it offers us and we become doomed to repeat its mistakes. I doubt there are many people reading this blog today who disagree with that sentiment.

Things get tricky, however, when we go fishing. Any single one of us can look back and pluck something from the past that serves our purposes today. We can use those historical examples to illustrate almost any “lesson” we want—and that becomes dangerous (as well as historically shaky). Does Virginia’s motto really advocate the assassination of presidents as Booth said, or the violent overthrow of Federal power as McVeigh suggested?

Some people will say “yes” to one or both of those questions, but really, who gets to decide? Don’t we have a lawfully elected government for a reason?

This is the question I suggest we ponder as we think about the question “What have we learned since the Sesquicentennial?” We kept that question intentionally broad so we could approach it from many angles and, I hope, illuminate the question by offering a variety of responses. I also hoped it would illuminate your thinking AND ours as a community of historians. We should all be constantly learning.

But we must be cautious of the inclination to find a “usable history” that proves those points we want to prove, that reinforces the lessons we want reinforced. History can only teach us if we approach it with an open mind. We need to be willing to learn and be willing to be taught.

That, of course, has been a central issue in contemporary events. It’s called “conformation bias.” We look for info that reinforces what we already know and (more insidiously) what we believe (whether our beliefs are based on fact or not). Those of us immersed in current events, particularly politics, can be tempted to look to the past and pluck out examples to illustrate our interpretations of current events. We can pluck out examples to show why we’re right in our thinking and the other side is wrong and look what will happen if our side doesn’t WIN! We misappropriate history when we do this.

As I reflect on “What have we learned since the Sesquicentennial,” I think of this question of usable history. As a society, we have not learned this lesson yet, but I do hope we have begun to learn that this lesson exists to be learned.

What we do with this new knowledge remains to be seen.

As we ponder that final thought, though, I will point to McVeigh and the lessons he chose to pull from history, and what he learned, and what the impact turned out to be. History can be abused just as easily as used—with real-world consequences.

————

For Related Content:

“Acts of Violence Against America” by Chris Mackowski, posted September 11, 2019

“Oklahoma City, JFK, and the Civil War” from the ECW YouTube page, June 10, 2019

You are braver than I am, Chris. I don’t think I could go to the Oklahoma City bombing museum any more than I could go to the Holocaust Museum in Washington or Wounded Knee. It is enough for me to know they are there and daily compel remembrance of horrible events in our past, in the hope we will do better in the future.

“Even as I reeled from the story of the attack itself, there was no time to grieve—and I wanted to.”

The Holocaust Museum in Washington provides a place to sit and grieve the devastating impact of the exhibits. Any museum that takes us back to such horrific events needs to understand the need for the audience to grieve for the victims.

I completely agree. The Titanic museum in Pigeon Forge does NOT have this and it’s sorely needed.

Agreed. I first visited the Holocaust museum as an 8th grader. It was overwhelming. And I remember sitting at one of those benches and sobbing. 2 years prior to this trip of mine was 9/11 so I had learned from an early age that evil really did exist it the world. It was hard for an 11 year old to watch the towers fall, and looking back on it that’s when my view of the world changed I lost a sense of innocence that day. My trip to the Holocaust museum brought about the same.

It’s extremely important that these places of reverence provide the space to sit, not just so people can grieve but also so that they can take it all in and reflect. It’s through our ability to reflect on our past that we will hopefully learn from it and strive to do better.

Kudos on a very thought-provoking piece, Chris. We live in an iconoclastic time. Yesterday’s heroes are all-too-often today’s goats, monuments are desecrated, and traditions are thoughtlessly cast aside. Historical facts are immutable in one sense, and a mirror on the times in which we view them in another. Every generation sees the past through its own lens. It cannot not do so. The fact that many of us see aspects of American history in a negative light these days has an analogue in how we see one another. To callously disregard another’s opinion without first attempting to understand the other’s point of view is akin to scrutinizing historical actions independent of the backdrop of the societal norms, mores, and values in the place and time in which they occurred. Both are uncharitable, and both lead to misunderstandings. Your point about the uses and misuses of history is a good one. I too hope that we will come to terms with history one day and learn that there is indeed a lesson to be learned about how we use it. We’re not there yet. Not by a long shot.

You touch on two related things that I think are especially important: attempt to understand one another and attempt to be charitable in our understanding of each other. Both are vital–and in shorter supply than I’d like. But by being honest in one’s desire to understand and by being empathetic, we can go a long way to getting along better and learning from–rather than just judging–the past.

Lovely article and well said. Keep on being you and learning. What else can we do?

Thanks. People have to want to be open to learning, though. It’s hard for someone to learn when he thinks he already knows it all.

We all must be careful of this. It can be difficult and unpleasant.

Great piece.

–Chris Barry

Thanks!

Wow, Chris, thanks for that piece.

As a former history teacher, I am concerned with the way that history can be “hijacked” by certain people or groups in order to foster a specific and destructive narrative. We see today the use of historical symbols that have been taken out of context and twisted to meet a particular world view.

It pains me to see the study of history being pushed aside by the STEM movement, but history teaches us valuable lessons about the past which we must examine in order to know how to apply lessons learned to the present.

Thanks for making me think so early in the morning!

Thanks, Eric–and thanks for your service in the classroom. I know how thankless that job must’ve been at times.

I hope I didn’t hurt your brain too early in the day! 🙂