The Black Brigade and the Defense of Cincinnati

Panic seized citizens of Cincinnati during the first days of September, as the potential consequences of the recent Confederate victory at Richmond, Kentucky became apparent. As defeated Federal soldiers retreated north toward Louisville, Queen City residents worried that Confederate general Kirby Smith might march his troops 75 miles north from his base in Lexington, Kentucky, assault the commercial center of the region, and choke off commercial traffic on the Ohio River. No significant opposition stood in his way.

Conflicting intelligence as to the location and movements of Braxton Bragg’s and Kirby Smith’s armies bedeviled US military leaders. Was Louisville or Cincinnati a more likely enemy target? Would Kentuckians rally to the rebel cause and swell Confederate forces enough to withstand a stubborn Federal defense? While Kentucky governor James Robinson pleaded with President Lincoln not to move Union soldiers from Louisville to Cincinnati, Ohio Governor David Tod summoned more than 15,000 men from the countryside whom he dubbed the “Squirrel Hunters” to help defend the city. In the meantime, Major General Lew Wallace took command of Union defenses on the south bank of the Ohio near Covington, Kentucky.

Cincinnati’s 3400 free blacks watched these developments with considerable trepidation. When news of the firing on Ft. Sumter reached the city in April 1861, local blacks formed a home guard militia but were forced to disband by Cincinnati mayor George Hatch, whose police insisted that the North was fighting “a white man’s war.” The city had close commercial ties to slaveholders across the river and a long history of racial violence. Among antebellum U.S. urban areas, only Philadelphia suffered more race riots. In the summer of 1862, conflicts between mostly poor Irish dock workers and black stevedores had erupted into seven days of rioting, driving nearly 90% of blacks from the steamboat trade.

General Lew Wallace declared martial law on September 2, 1862. That afternoon the mayor ordered “every man, of every age, be he citizen or alien” to assemble and defend the city and designated his police force as Wallace’s provost guard. Local black men, knowing they were not considered citizens and conscious of the rebuff they had received the previous year, hesitated. The few that did report were told by police that the order was not meant for them. Meanwhile, military authorities decided to impress free blacks to help build fortifications across the river. When city police were informed of this, they assembled a detail that included gangs of local ruffians, barged into homes and workplaces, and forcibly marched black males to a mule pen on Plum Street, across from the cathedral.

Henry Howe of the Cincinnati Emergency Volunteers described the scene: “The colored men were roughly handled by the Irish police. From hotels and barber shops, in the midst of their labors, these helpless people were pounced upon and often bareheaded and in shirtsleeves, seized, driven in squads at the point of the bayonet, and gathered in vacant yards and guarded. What rendered this act more than ordinarily atrocious was that they, through their head men, had at the first alarm been the earliest to volunteer their services to our mayor for the defense of our common homes. It was a sad sight to see human beings treated like reptiles.” After being detained a few hours, they were taken across the river.

On Thursday, September 4, the Cincinnati Gazette protested the harsh handling of the impressed black men. “Let our fellow-soldiers be treated civilly,” the editor pleaded, “and not exposed to any unnecessary tyranny, nor to the insults of poor whites.” The Gazette maintained that Cincinnati blacks should have been invited to volunteer, “then there would have been an opportunity to compare their patriotism with that of those who were recently trying to drive them from the city.”

General Wallace, conscious of the considerable anti-slavery feeling among a sizable but influential minority of Cincinnati residents, assigned Judge William Martin Dickson command of what became known as The Black Brigade. Dickson was a friend to the local black community and respected their dignity. He allowed them to return to their homes and prepare for their new assignments. The next day, 300 volunteers who had not been among the more than 400 physically driven from the city joined the brigade, crossing the river walking tall as freemen defending their homes and families.

Acting camp commandant James Lupton presented more than 700 men with a national flag with “BLACK BRIGADE OF CINCINNATI” inscribed on its folds. “Men of the Black Brigade, rally around it!” Lupton admonished them. “Slavery will soon die; the slaveholders’ rebellion, accursed of God and man, will shortly and miserably perish.” Then the first formal organization of black men for military purposes in the North during the Civil War got to work— hard and exhausting toil, now cheerfully performed with a sense of duty, rather than being compelled by brute force. They received no pay for their first week of work, then earned a dollar per day during the second week. By week three, Dickson had succeeded in raising their daily pay to $1.50, the same wage earned by several thousand white coworkers.

The hardy men felled trees, constructed roads, built breastworks, and dug rifle pits for nearly three weeks. Confederate General Henry Heth’s force of between six and eight thousand soldiers came within a few miles of the river near Fort Mitchell, but did not engage. The new defensive works and the presence of more than 25,000 Union soldiers alongside local militia and Squirrel Hunters proved a formidable deterrent. Heth’s forces departed and the Federal Army focused on safeguarding Louisville.

On September 20, The Black Brigade disbanded. The 705 surviving members of Cincinnati’s Black Brigade marched through the streets of Covington, Kentucky shouldering shovels and pickaxes, then crossed the pontoon bridge. Martial music played and banners rippled in the breeze as the men strode proudly through the main streets of the Queen City. Judge Dickson dismissed them with an emotional speech: “The sweat-blood which the nation is now shedding at every pore is an awful warning of how fearful a thing it is to oppress the humblest being. Until our country shall again need your services, I bid you farewell.” Their contributions to the Union war effort, as Dickson suggested, were only just beginning.

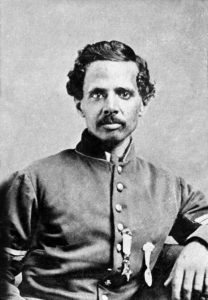

Brigade members who built fortifications, along with another 300 blacks who served in other capacities in camps, in the city, and on gunboats, later volunteered as soldiers with the famous 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry, Louisiana’s Corps d’Afrique (renamed the 75th US Colored Infantry), and other regiments. Powhatan Beaty, who earned the Medal of Honor for his heroism at the Battle of Chafin’s Farm while fighting for the 5th US Colored Infantry made the improbable journey from shoveling dirt across the river from Cincinnati to a role as a principal actor in a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. His son later won a seat in the Ohio state legislature. For the first time in their lives, these men were given the opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and fight in an official capacity for the liberation of their brothers and sisters in bondage.

The ultimate fate of many of the men who served in the Black Brigade remains unknown to this day. Fortunately, recent efforts by Cincinnati citizens to honor their service are prompting historians to delve deeper into their unusual story. A monument to the Black Brigade was dedicated in Cincinnati’s Smale Riverfront Park in September 2012, marking the 150th anniversary of their service. In 2020, local historian Darryl R. Smith republished black community leader Peter Clark’s 1864 pamphlet account of the brigade, adding footnotes, biographical sketches of prominent members, illustrations, and selected readings. Understanding the role that free blacks played in the Civil War as significant stakeholders and active agents of enslaved people’s liberation is important. In 1862, the focus of the Lincoln administration’s war agenda expanded from its primary goal of preservation of the Union into a measured yet sustained advance toward human freedom and racial justice, issues we continue to struggle with in our time.

David T. Dixon’s latest book is Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2020).

Sources:

Clark, Peter H. The Black Brigade of Cincinnati: being a Report of its Labors and a Muster Roll of Its Members; together with Various Orders, Speeches, etc. Relating to It. Cincinnati: Joseph B. Boyd, 1864.

Harding, Leonard. “The Cincinnati Riots of 1862.” Bulletin of the Cincinnati Historical Society, Vol. 25, No. 4 (October 1967), 229—39.

Howe, Henry. Historical Collections of Ohio. Volume I. Cincinnati: C.J. Krehbiel & Co., 1888, 774—777.

Masters, Daniel A. Echoes of Battle: Annals of Ohio’s Soldiers in the Civil War, Volume I: Philippi to Perryville. Perrysburg, OH, Columbian Arsenal Press, 2021 (forthcoming).

Taylor, Nikki N. Frontiers of Freedom: Cincinnati’s Black Community, 1802 – 1868. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005.

Was Cincinnati really threatened? We will never know. But the rapidly constructed and sound defences ensured that the city would not become “easy pickin’s” to a Confederate force attracted to a target of opportunity, with potential for swift capture and substantial ransom.

And the case of Cincinnati provides an uneasy, “What if…” What if local black men, fighting against the invasion of their Northern homes, and not recognized as “authorized military members” were taken prisoner? At this early period the South did not recognize Black soldiers; and officers in command of Black soldiers were to be considered Outlaws, subject to summary execution.

It is probably for the best that this question remains unanswered. But, If ever there was a case for reparations for participation in the Civil War, the descendants of those hardy men who prepared defences in Kentucky and Cincinnati in 1862 possess a solid claim.

Wonderful article, David! Nice to see these men mentioned, and I appreciate the mention of the expanded booklet as well. Thank you!