Every Free Able-Bodied Male Citizen: Another Example of Militia Readiness in Antebellum America Part IV

A few years ago, I wrote a series concerning antebellum militias in America. I gave a thoughtful introduction, explaining the state of local militias between the Revolution and the Civil War, then wrote about a northern militia group and a southern one. It was not until the last couple of years that I realized I had made a glaring omission.

The northern militia was the U. S. Zouave Cadets, drilled by Colonel Elmer Ellsworth. Every man except two went on to serve as an officer in the Union Army, and the men that did not ended up in charge of all the troops sent to the U. S. government from “the great state of Illinois.” The southern militia was a mounted group–the Virginia Black Horse Cavalry. They escorted John Brown to the gallows, led by J. E. B. Stuart, and were the seed company of Stuart’s famous mounted Confederate cavaliers.

- Every Free Able-bodied White Male Citizen: Two Examples of Militia Readiness in Antebellum America, Part I

- Every Free, Able-bodied White Male Citizen: Two Examples of Militia readiness in Antebellum America, Part II

- Every Free, Able-bodied White Male Citizen: Two Examples of Militia Readiness in Antebellum America, Part III

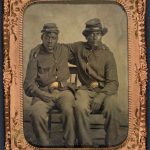

The missing militia is the Louisiana Native Guard. Based in New Orleans, this group of free men of color (hommes de couleur libre) existed in various guises from the colonial era up to the Civil War.

This unique group’s rights, men descended from French and Spanish men and slave women, changed depending upon who was in control of Louisiana. Initially, these men could own land, businesses, and even slaves. They could vote, go to school, and serve in the military. They created militia units that served in the American Revolution. Then, America acquired Louisiana in 1803, and by 1812 the status of free men of color changed. The Louisiana Constitution gave the right to vote to white men of property, and there were no exceptions. When free men of color were left out of politics, their status began to decline. In an attempt to regain position, militia groups were formed, including some who fought with Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812.

April 12, 1861–many consider the Battle of Fort Sumter the beginning of the Civil War. The shots fired at the little fort were heard as far away as New Orleans, where several free men of color decided to form military companies to protect New Orleans. In an announcement published in the Daily Picayune, the men declared that they were prepared to defend their homes “against any enemy who may come and disturb its tranquility.” The Daily Crescent newspaper reported: “Our free colored men … are certainly as much attached to the land of their birth as their white brethren here in Louisiana. … [They] will fight the Black Republican with as much determination and gallantry as any body of white men in the service of the Confederate States.”[1] Hundreds of men went to then-Governor Thomas O. Moore, asking for his support for the newly-created Louisiana Native Guards Regiment. This regiment was accepted into the state militia, but the governor refused to add them to the number of recruits needed for the currently-forming Confederate army.

On April 24-25, 1862, New Orleans fell to the Union Navy under the command of Admiral David Farragut. By May 1, Major General Benjamin F. Butler arrived to take over the city and impose military rule. After the Battle of Baton Rouge in August, Gen. Butler requested reinforcements to defend New Orleans, but none were forthcoming. In desperation, Butler informed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that he planned to raise a regiment of free blacks. On September 27, 1862, Butler mustered the First Regiment of Louisiana Native Guards into Union service, making it the first sanctioned regiment of African-American troops in the United States Army. Although a point of argument, muster rolls indicate that Butler’s Guards were mostly runaway slaves, not free men with connections to prominent white families. Professor Terry L. Jones, in a piece for the New York Times’ “Opinionator, offers this anecdote:

During an inspection, the Native Guards’ white colonel told another officer: “Sir, the best blood of Louisiana is in that regiment! Do you see that tall, slim fellow, third file from the right of the second company? One of the ex-governors of the state is his father. That orderly sergeant in the next company is the son of a man who has been six years in the United States Senate. Just beyond him is the grandson of Judge_______ … ; and all through the ranks you will find the same state of facts. … Their fathers are disloyal; [but] these black Ishmaels will more than compensate for their treason by fighting it in the field.”[2]

Although the colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors (field grade officers) were all white men, the line officers were all black. André Cailloux–formerly Confederate Lieutenant–was named captain of Company E, which contained many former members of the 1861 iteration of the Louisiana Native Guard. By late 1862, so many runaway slaves had come forward to join the Native Guard that two more regiments were formed.[3]

When Butler was ordered to Virginia, he was replaced by Major General Nathaniel P. Banks as Commander of the Gulf. Banks was not nearly as sympathetic to the plight of the formerly enslaved as Butler had been. He proceeded to purge the Guard of its black line officers. He was only partially successful. All the black line officers of the 2nd Regiment had resigned by February 1863. Most of the line officers in the other two regiments remained. The Native Guard performed fatigue duty and guarded railway depots between Algiers and Brashear City (now New Orleans to Morgan City). Their pay was less than that of white soldiers, and they were not given the respect they felt they deserved. By mid-1863, their number had diminished to about 500. It was at this time that the Native Guard was offered its first chance at combat. General Banks was to join General U. S. Grant’s forces in Vicksburg. Before he could do so, he was also ordered to control the waterway between Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana. Mistake after mistake ensued, and finally, in May 1863, Banks decided to besiege Port Hudson. With his army were the remains of the First and Third Regiments of Native Guards. This would be the first time black soldiers took part in a significant Civil War battle. Banks failed to take Port Hudson twice (May 27 and June 14) due to inadequate surveillance, which resulted in failed attacks along the river.[4]

Lieutenant Cailloux died heroically in the first assault on May 27. Due to unclear reasons, his body and those of the other 169 men of the Louisiana Native Guard were left on the battlefield until the Union surrender of July 9. Cailloux was given a large public funeral in New Orleans on July 29.[5]

The most significant contribution the Native Guards made at Port Hudson was showing their white comrades and superiors that black soldiers would fight as well as white soldiers. Many officers and men remarked on the Native Guards’ bravery and heavy losses in the days following the doomed attack. Largely because of the Native Guards’ service at Port Hudson, Union officers began recruiting African-Americans for combat roles. In June 1863, the Louisiana Native Guard was dissolved. The 200-300 men who stayed in service became the seed troops of the newly-formed Corps d’Afrique. These soldiers were poorly treated once again. Many resigned or deserted. After serving in the 1864 Red River Campaign, they were re-designated the 73rd, 74th, and 75th United States Colored Troops. When the war ended, over 175,000 black men had served in the USCT. One hundred members of the original 1,000 Native Guard members were still serving in the 73rd and 74th Regiments.

Often the Louisiana Native Guard is cited as proof that there were loyal black men serving in the Confederate army. Just the opposite was true. The unit—in any iteration—was never accepted into Confederate service. By September 1862, many former members of the Native Guard were wearing Union blue and continued to do so until almost two years after the war, when their terms of service were judged to be up.[6] After the Civil War, many black soldiers were sent West to fulfill their enlistments, becoming famous as Buffalo Soldiers.

[1] Jones, Terry L. “The Free Men of Color Go to War.” New York Times Disunion blog, The Opinionator. October 19, 2012.

[2] Jones, Ibid.

[3] Frenchcreoles.com. “The Louisiana Native Guard-Pt. 2.” http://frenchcreoles.com/frontpage.html.

[4] Work, David. Lincoln’s Political Generals. Urbana, Illinois; University of Illinois Press, 2012. 104

[5] Frenchcreoles.com

[6] Levin, Kevin M. Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Chapel Hill; The University of North Carolina Press, 2019. 45