Stephen Hurlbut and the Quest for Redemption

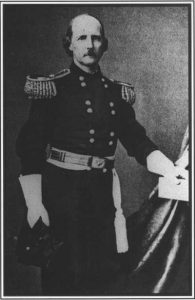

Few Civil War generals and politicians had an odder career than Stephen Hurlbut. He was born in South Carolina to Yankee parents, but fled north becoming a political power broker in Illinois. As a politician he was mostly a back room dealer, serving only two terms in Congress and two stints as a diplomat in South America. Although a major player in Illinois, he never achieved a top position within the state’s admittedly crowded political arena. His greatest strength was his oratory. Abraham Lincoln called him “the ablest orator on the stump that Illinois had ever produced.” Hurlbut used his talent to aid Lincoln’s election. The 16th president never forgot that, and during the Fort Sumter crisis, Lincoln sent Hurlbut to Charleston to investigate matters weeks before the war started.

Hurlbut’s influence assured him a generalship less than two months after the shooting started. He was commissioned a general and much of his military career was a frustrating attempt to achieve the recognition that had so far eluded him. Much of it was due to his character flaws. He was an alcoholic given to cruelty and violence, even getting into a drunken rage and picking a fight with a teamster who proceeded to thrash him. In an age of corruption he was considered exceptional. He gambled away his money as a youth and resorted to cheating at cards, which was one of the reasons he fled South Carolina.

Hurlbut’s reputation and his exactness as a drillmaster made him unpopular with his men. In 1861 he was tasked with countering Missouri guerillas, but failed in his duties and took to the bottle. He was arrested, but Lincoln restored him in December 1861. He was dispatched to St. Louis, Missouri where he trained troops alongside William Tecumseh Sherman. Both men were in disgrace, but each was connected to powerful politicians and were good drillmasters.

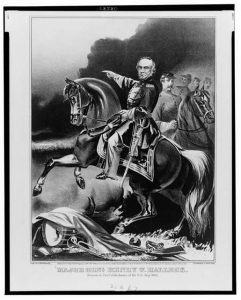

Henry Halleck stayed close to each man. Often portrayed as disliking political generals, in reality Halleck could be supportive, if the commanders showed an attention to military detail. It also helped to be a Republican, and Halleck was smart enough to know that if he cultivated Hurlbut Lincoln would be appreciative. As for Sherman, his brother was a Republican senator who benefited from his early support for Lincoln’s candidacy. Halleck, whatever his faults, was a master of the politics of war. He made sure both Sherman and Hurlbut received division command under Ulysses S. Grant. They were the vanguard of the Army of West Tennessee, as it massed at Pittsburg and Crump’s Landing.

Of all the division commanders under Grant in April 1862, Hurlbut at first seemed to have the dimmest prospects. Sherman had not done well up until then, but he had his political connections and Halleck’s friendship. Lewis “Lew” Wallace was lionized in the papers after Fort Donelson and along with John McClernand received a promotion. William H. L. Wallace struck up a warm friendship with Grant and was popular with most of the army. Benjamin Prentiss and Grant did not like each other, but Prentiss was an up and coming Republican who had amassed a favorable record in 1861. By contrast, Hurlbut was considered a cruel and incompetent drunk, who owed his rank solely to Lincoln’s favor.

One underrated quality of Grant’s was his political acumen. He promoted and supported friends. To win favor with Halleck, he was favorable to anyone Halleck liked. Also, Grant’s patron, Elihu Washburne, was in 1862 on good terms with Hurlbut. While Grant never struck up a friendship, he was cordial to Hurlbut, unlike his dealings with Lew Wallace, Prentiss, and McClernand.

Hurlbut’s division was rife with command tension. Most officers held him in low regard. Colonel Nelson Williams, Hurlbut’s brigade commander, quarreled with him in Missouri and oversaw his arrest. There was an active petition among the men to have Hurlbut transferred to another command.

Despite Hurlbut’s unpopularity, he showed promising signs before the battle of Shiloh. Hurlbut requested that his division should be placed in front but he was turned down. It showed that Hurlbut had an aggressive streak. On April 4, while Sherman’s men skirmished with the Confederate vanguard, Hurlbut moved his division to Sherman’s camp. As he arrived Hurlbut was told by Sherman, via courier, to go back, which led his men to jeer him. Hurlbut admitted “no regiment…desired to be under my command…” He was demoralized by the episode, but it showed he was willing to take the initiative.

On April 5, a local told Lieutenant Colonel William Camm of the 14th Illinois the Confederates were in strength at Purdy. After meeting with Hurlbut, they decided to send out a patrol. Hurlbut then told Camm to stay in camp. Hurlbut’s sudden caution might have been due to Sherman’s disapproval of his actions on April 4.

On April 6, 1862, as the first sounds of battle came, Hurlbut moved to support Prentiss, who was further ahead. Prentiss’ division melted before Hurlbut could reach him, and he found his division far forward in the Sarah Bell Field. He stayed there to connect with David Stuart’s brigade to the east, but also to cover Prentiss as he reformed his division. The position was exposed and Confederate artillery fire was heavy and fairly accurate. Williams was thrown from his horse. He was paralyzed and later resigned his commission. When a staff officer asked Hurlbut to go to the rear amid the shelling he laconically stated “Oh, well, we generals must take our chances with the boys.”

Captain John Blymier Myers’ 13th Ohio Battery came under fire from Robertson’s Alabama Artillery. The 13th Ohio Battery was poorly trained and in an exposed position. The men abandoned their cannon, leaving five to the Confederates while the sixth was brought back to Pittsburg Landing. Hurlbut described the men as “cowards, who disgraced their state and their flag” and called Myers “scum.” He had the battery disbanded and stripped Myers of his rank. Although many blamed Hurlbut for the battery’s poor position, it was clear that Myers had failed under fire. While Hurlbut might have simply been covering his mistake, it also sent a clear message to the men.

Hurlbut readjusted his lines and held the left flank for five hours. Union artillery and musket fire was heavy enough to prevent a major Confederate attack until 1:00 p.m. Albert Sidney Johnston, the Confederate commander, formed an attack and turned Hurlbut’s left. The Union division might have been routed, but the Confederates became disorganized and Hurlbut gamely reformed his lines even as other regiments attacked. Johnston for his part died, leading to a short lull in that part of the battlefield.

By 4:00 p.m. renewed Confederate attacks were shoving Hurlbut’s men back. As Hurlbut gave way, he notified Prentiss that he had to retreat. Hurlbut later wrote “The orderly was never heard of again and General Prentiss did not receive the notice.” Hurlbut also seemed to think McClernand could guard Prentiss’ flank. Either Hurlbut misunderstood the situation, or he saw it as a cheap way to besmirch McClernand, who was a political opponent back in Illinois.

Hurlbut directed gunboats to fire into the area of Cloud Field, the bombardment beginning at 5:35 p.m. He then reformed his lines for the final defense. Luckily, his part of Grant’s last line was not tested, as night came on and P.G.T. Beauregard, who replaced Johnston, ordered his exhausted men to disengage.

On April 7 Hurlbut gamely led his men back into the fray and they aided in forcing back the Confederates in the late morning. When all was over, few could doubt that Hurlbut was a capable and brave combat commander. Whatever his connections to Lincoln, or the mild favor of Grant and Halleck, Hurlbut earned his promotion to major general fair and square at Shiloh. Hurlbut, the drunk card-cheat known for shady land deals was now a true blue war hero.

Sadly, Hurlbut rarely showed much ability after Shiloh. He commanded XVI Corps but mostly stayed in the rear at Memphis. His command became notorious for corruption and poor treatment of Confederate prisoners. Later in 1864, he was transferred to New Orleans. There he supported conservative elements and over time lost some of Lincoln’s favor, even suffering a court of inquiry. Only Grant remained loyal to him in 1865. But for the men he led on April 6, 1862 many of whom had never been in a battle, they could recall in their old age the sight of Hurlbut on his horse in a resplendent uniform, unafraid of death and coolly directing his men in the fight of their lives.

Very interesting insight into Hurlburt’s life and his performance at Shiloh.

I firmly believe everyone has their moment and Hurlbut’s certainly was April 6-7, 1862.

Outstanding bio, recall him at Shiloh but knew little about him before or after.

Thanks. I recommend checking out Lash’s biography of Hurlbut. It is first rate.