Book Review: Stonewall Jackson, Beresford Hope, and the Meaning of the American Civil War

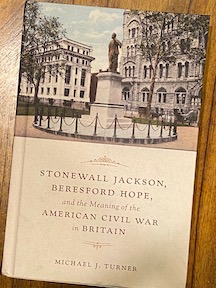

Stonewall Jackson, Beresford Hope, and the Meaning of the American Civil War

Stonewall Jackson, Beresford Hope, and the Meaning of the American Civil War

By Michael J. Turner

LSU Press, 2020; $50.00, hardcover

Reviewed by Chris Mackowski

As the last year has powerfully reminded us, Civil War monuments all have stories to tell. Take, for instance, the story Michael J. Turner ably tells in his 334-page book about the Stonewall Jackson statue that stands in Capitol Square outside the Virginia state house in Richmond. Stonewall Jackson, Beresford Hope, and the Meaning of the American Civil War in Britain carefully, objectively recounts the story of the statue and, in doing so, peels open a complex tale of international relations and a cult of personality.

Hope is largely forgotten today except maybe as a member of the family from which the famous Hope Diamond came from. Hope was a Conservative member of the British Parliament, an outspoken (and wealthy) supporter of the Church of England, publisher of the widely read Saturday Review, and influential Confederate sympathizer.

In the first part of the book, Turner uses Hope as a springboard for examining the complicated attitudes the British had toward the United States in general and toward the Civil War specifically. Those views are most commonly boiled down to an oversimplified thumbnail: “The British needed Southern cotton but opposed slavery.” As Turner explains, “British opinion is not easy to pin down, for it was subject to many forces, political and social, local and regional, and it was highly sensitive to the course of events in America.”

Turner’s study explores those many forces, using as his lens Hope’s efforts to rally pro-Southern sentiment. Hope himself makes a fascinating character study, but Turner does double-duty by situating that personal story in the larger context of international politics and, more importantly, within current historiography of the American Civil War as an international event (see Andrew Lang’s A Contest of Civilizations as an example).

In the second half of the book, Turner turns his gaze to Stonewall Jackson, who captured British imagination unlike anyone ever before. As Confederate fortunes waned by the spring of 1862, Jackson’s successes in the Shenandoah Valley provided a bright spot. “As increasing attention was given to Jackson’s efforts and they compensated for disappointments elsewhere,” Turner explains, “his reputation—while merited—also became a political and psychological device.”

Turner explores those political and psychological elements in detail through a wide variety of press accounts and letters. “Coverage was overwhelmingly positive,” Turner assesses, providing ample examples. Jackson was, papers variously and collectively said, remarkable, dashing, clever, aggressive, brave and energetic, daring and adventurous, and a cross between Cromwell and Napoleon, with a little Garibaldi thrown in for good measure.

“Jackson’s heroic status could not be denied,” Turner says, but the public also craved to know about the man behind the legend, too, and even after Jackson’s accidental death at the hands of his own men at the battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, “There was no weakening of interest in him or falloff of discussion about him.”

The perfect example of this is G. F. R. Henderson’s Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War, published in two volumes in 1898. Henderson, himself a respected officer and an instructor of military history, chose to look at the war with Jackson as its central organizing principle—a view not uncommon among his countrymen by the turn of the century. Turner calls Henderson’s biography “One of the most enduringly influential and important books about Jackson.” (That it’s still commonly available in the “discount books” section at places like Barnes & Noble, reprinted under the bookstore’s own imprint, only underscores Turner’s point about its endurance.)

Turner’s many threads come together when Hope calls for a statue to Jackson in 1863, before Jackson’s hardly cold in the ground. “Beyond all the writings, speeches, pictures, poems, songs, and the use of his name and fascination with his life and the lessons it could teach, British regard for Jackson was given solid material expression,” Turner writes. Although not unveiled until 1875 because of various delays, the statue of Jackson in Richmond’s Capitol Square, funded through private donations and “presented by English Gentlemen,” became “A tangible sign of the high esteem in which Jackson was held by the British people.”

Turner’s study avoids the hero worship he chronicles. He talks about the cult of personality without drinking the Flavor-Aid. The result reminds me of watching old TV clips of Elvis Presley doing his thing for screaming fans: I don’t scream along with them, but I’m fascinated by their screaming.

Louisiana State University Press is to be commended for publishing Turner’s book right now. In an atmosphere that’s so politically and emotionally charged, the word “monument” can be a flashpoint. Turner’s thorough work has the patience to illuminate.

What an excellent review. I have long been interested in the history of that particular statue, and hope it can remain where it is.

Thank you!