The Crater Sent a Monster Home to Maine

ECW is pleased to welcome back Brian Swartz, author of the new Emerging Civil War Series book Passing Through the Fire: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain in the Civil War. Brian adapted this post for us from a series of posts published on his blog Maine at War on March 20, March 27, and April 3, 2014.

The massive explosion that created The Crater and stunned James J. Chase followed him home to Maine.[1]

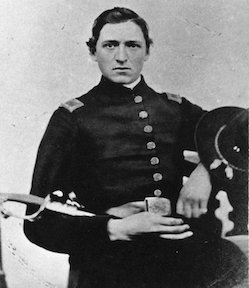

Hailing from Turner in Androscoggin County, the 16-year-old Chase joined the army in August 1863. Showing talent and leadership capabilities, he received a commission and a transfer to the 32nd Maine Infantry Regiment in late winter 1864 as second lieutenant, Co. D.

He arrived at Petersburg in July and reported to the 32nd’s commander, Col. Mark Wentworth. Guided by a soldier named Peare, Chase navigated the trenches, ran across an open ravine as Confederate bullets whizzed past, and “at about three P.M. we reached the regiment.”

He found Capt. H. R. Sargent, who commanded the companies deployed perhaps 60 yards from Confederate positions. Ordered by Sargent “to assume command” of Co. D, Chase “found thirteen privates and three non-commissioned officers, of the full company of one hundred I left scarcely three months before.”

Another regiment relieved the 32nd Maine in the evening on Tuesday, July 26; the Maine boys returned “to our retreat in the pine woods” behind the Union lines, according to Chase. Off to the right he saw Union “sappers and miners carrying powder to the mine (tunnel)” dug from the Federal lines to a point beneath the Confederate fort atop Cemetery Hill.

Excavated by Pennsylvania coal miners, the tunnel ran 511 feet to a gallery excavated about 50 feet beneath the Confederate fort. The miners packed the gallery with four tons of gunpowder.

Plans called for the mine to blow up at 3:30 a.m., Saturday, July 30, to create a gaping hole in Southern lines. The 32nd Maine Infantry would charge after the mine exploded. “Grasping my sword at my side, I hurriedly took my place in the line now being formed,” Chase said. “Silently we marched out of the woods and along the covered way.

“By the light of the full moon we could distinctly see the outlines of the enemy’s fort on Cemetery Hill, not 300 yards distant,” Chase said. At 3:15 a.m. “our troops were in position.” At 3:30 a.m., “contrary to our expectations no explosion took place.”

Two Pennsylvania soldiers scurried into the tunnel to splice and light a new fuse. They rushed to safety,

The mine exploded at 4:44 a.m. The detonation “seemed to occur in slow motion,” wrote historian Bruce Catton. Soldiers experienced “first a long, deep rumble, like summer thunder rolling along a faraway horizon, then a swaying and swelling of the ground up ahead, with the solid earth rising to form a rounded hill,” which “then . . . broke apart, and a prodigious spout of flame and black smoke went up toward the sky. . . .”

“O horrors! was I in the midst of an earthquake?” Chase exclaimed. Looking at Cemetery Hill, “I beheld a huge mass of earth being thrown up, followed by a dark lurid cloud of smoke.”

Charging with their brigade, the 32nd Maine boys “found a large hole or crater made by the explosion, shaped like a tunnel, forty feet deep and seventy feet in diameter,” Chase said. “We at once took shelter in the deep crater . . . some jumped in, some tumbled in, others rolled in.” He jumped into the crater, where “beneath our feet were the torn fragments of men, while upon every side could be seen some portion of a man protruding from the sand.”

Chase soon “climbed up a pile of earth . . . thrown up by the explosion” and immediately spotted “a large body of the enemy forming in a deep ravine at the foot of the hill.” Sliding into the crater to warn Sargent, who was crawling up “a pile of earth similar to the one I had climbed,” Chase stood still too long.

A Confederate “sharpshooter from the pine grove on our left” fired. “The bullet struck me near the left temple and came out through the nose at the inner corner of the right eye, throwing out the left eye in its course.” Chase reeled in agony. “Staggering and reeling I walked across the trench, the blood spurting before me from my wound.”

Vaguely seeing Capt. Joseph Hammond beside him, Chase said, “Captain, I must die.”

“Yes, Chase, you have a death shot,” Hammond replied.

As comrades checked on him, Chase begged “for a looking-glass.” Gazing into it, “I could see no resemblance to my former self. My left eye lay upon my cheek, while my nose appeared to be shot off.”

Sargent administered rudimentary medical care and used a penknife to extract “some loose pieces of bone projecting from my nose into my remaining eye,” Chase remembered

“I want to save that eye, for it is a great blessing to have one if you can’t have two,” Sargent said.

Evacuated to a waiting ambulance, Chase “shrieked with pain” as it jolted and careened toward a field hospital. Passing out on the operating table, he awoke to find his head bandaged “and the blood . . . washed from my face.” Evacuated to City Point, he was carried onto a hospital transport. With him went “all my earthly possessions”: his sword and “the bloody shirt and trousers I wore.”

Chase’s father soon arrived at the Washington, D.C., hospital where the wounded lieutenant received excellent medical care. The Chases later left for Maine; after arriving in Auburn by train on Thursday, Aug. 18, they went to board a carriage for the final journey home.

A woman passenger vehemently protested, “Don’t let him come in here; I can’t ride with such a horrid looking creature!” The Chases shifted to a stagecoach.

The next day, friends gathered around James Chase as he examined his face in a mirror. He saw the same “horrid looking creature” denied transportation by the shrieking passenger—and Chase did not blame her. Swollen and bandaged, his face resembled nothing human.

He recovered and eventually joined the Maine State Guards in January 1865. Mustering out, he married and had children.

But The Crater followed him home. On Tuesday, December 10, 1872, “I was attacked with severe pain in my [right] eye, which increased through the day.” Having experienced similar bouts in the past, Chase expected the pain would subside.

“At sunset . . . all objects before me began to fade from my vision,” a frightened Chase realized. He called too late for a doctor; “before he reached me all nature was to me a blank.

“I had looked upon my wife (Drusilla) and little ones (daughters Jenny and Ella) for the last time.” Chase admitted. He groped to find and pick up his 3-year-old daughter (Ella), whom he would never “see” again.

Now permanently blind, “my burden seemed more than I could bear,” he commented three years later. “But . . . I now appreciate the many blessings bestowed upon me, which I am permitted to enjoy.”

[1] Sources: Bruce Catton, Stillness at Appomattox, (New York, NY1953), 242; James J. Chase, The Charge at Day-Break, (Lewiston, ME, 1875).

What a horrific wound! Poor guy… what a hero.

How long did he live?

I traced the Chases to still living in Turner in 1880, but they vanish from that town afterwards. I cannot find them elsewhere, so far.

What happened during the rest of his life? What a tragic horror???

I am not sure, John. James did write his memoir about being badly wounded at the Crater, and I sense he may have dictated the part about where he went blind.

Thank God his story and sacrifice has been shared and remembered ..so many will never be ..

You are so correct …

Great article about another piece of our great national tragedy. It truly was a sad affair. I found Lt. Chase living in Old Orchard in 1900. In 1910, he is living with his brother in Turner. He passed on June 1, 1918 at Saco. He is buried in Laurel Hill in Saco. I think we all mourn the life that could have been.

Thank you for sharing this information. Did you find any trace of his wife, Drusilla, or their children? I could not find them through the 1890 and 1900 censuses.

He was with his wife in 1900. Ella and two teenagers are with them then. He is listed as married while living with his brother in 1910.

Found Drusilla in the 1910, 1930 and 1940 Censuses. She seems to have remained in Old Orchard or Old Orchard Beach. No children were with her.

Forgot…the 1890 census records were destroyed.

What a splendid man and a terrible tragedy. Thank you for sharing the story of James Chase with us.