George Disney Atop Rocky Face Ridge

“I don’t think I can do this.” My voice, tense with anxiety, barely reached my husband who had already set out on the trail, leaving me in the church parking lot at the bottom of the mountain.

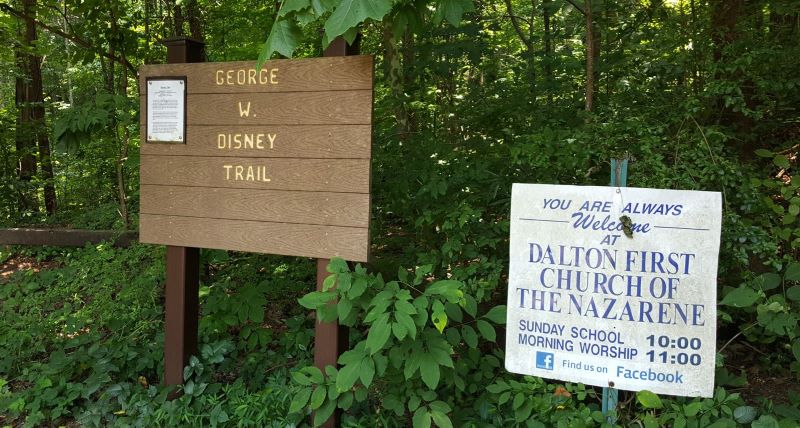

I looked back to the bulletin board, skimming over the sign regarding the George Disney Trail. Phrases like “short sharp climb,” “steep ascent,” leading up to the sentence, “About half way up, the trail becomes even steeper,” gave me a healthy dose of hesitance and realism. Stephen Davis’ ECW book about the Atlanta Campaign cautioned this journey, saying it was for the “hale and hardy.” I’m no athlete and I’m certainly more comfortable in an office chair with a cup of coffee, surrounded by books. There, my only concern is getting a chill from the air conditioning or a papercut, not dehydration or heat stroke.

I repeated my worries to Jared, who finally heard me and came back. “Don’t you want to see the grave?” he asked, a note of impatience in his words. It had already taken us half an hour to find the trailhead using Google Maps and we had stopped at several places following the ECW driving tour before that afternoon.

I glanced back to the part of the sign that detailed the death of George Disney during the Battle of Rocky Face in February of 1864. “Well, yeah, but… this is supposed to be ‘the most challenging short trail’ in the state of Georgia. It’s over two miles.” I could see the headlines already, “Woman Dies of Exhaustion on Rocky Face Ridge.” Worst of all, I’d miss the Emerging Civil War Symposium the following week. (We visited Rocky Face Ridge in late July)

“I think you can do it. Just bring an extra water bottle.”

His confidence and optimism – two traits that endeared me to marry this man – was beginning to irritate me. He had been my trail partner on many Civil War trips, but I didn’t want this to be the last hike. Was it worth it? Surely there was a picture of the grave online somewhere. There was no need to put myself through the hardship.

I spoke my mind once more to Jared, but he came back with, “If you don’t do this now, you may not get another chance. Are you going to regret not getting the picture?”

That’s the sort of logic that has driven me to travel, learn, explore, and step far out of my comfort zone. That’s the logic that gets me every time.

I gave in and followed him up the first few steps of one of the most arduous hikes of my entire life. I only hoped that I wouldn’t regret it.

After the Army of Tennessee had been routed by the Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chattanooga on November 25th, 1863, a shift in command took place that would shape the following spring campaign of 1864. Braxton Bragg resigned from his longtime post as Confederate commander of the army, paving the way for the return of Joseph Johnston. “Old Joe” took command on December 27th at Dalton, Georgia and went to work on rebuilding the morale of the some-53,800 Confederate troops.

At the same time, the leadership of the Federal armies in what was considered “the west” experienced a facelift. General Ulysses S. Grant, then commander of the “Military Division of the Mississippi” was moving up to take the reins of all Federal forces, effective March of 1864, as lieutenant general. Major General George H. Thomas, the “Rock of Chickamauga” and the commander responsible for pushing Bragg back into Georgia, was recommended as Grant’s replacement in the Department. Grant had other plans and appointed Major General William Tecumseh Sherman. It was Grant’s hope that Sherman would “move against Johnston’s army, to break it up and to get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their War resources.” Hindsight and history reveals Sherman accomplished this task rather effectively.

Before Sherman could make his first opening maneuvers of the 1864 campaign against Johnston, he led a raiding campaign with the Army of the Tennessee from Vicksburg to Meridian with the sole intent to tear up railroad tracks and burn any form of infrastructure that would aid in the Confederate war effort. 26,000 Federal soldiers cut a path across the width of Mississippi, making their way toward north Georgia. There, he would join forces with Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland and Major General John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, bringing his total forces up to about 110,000. He outnumbered Johnston’s forces from the Army of Tennessee and Army of the Mississippi two-to-one. With these superior numbers, he planned to continually outflank Johnston, pushing him through north Georgia to the gates of Atlanta.

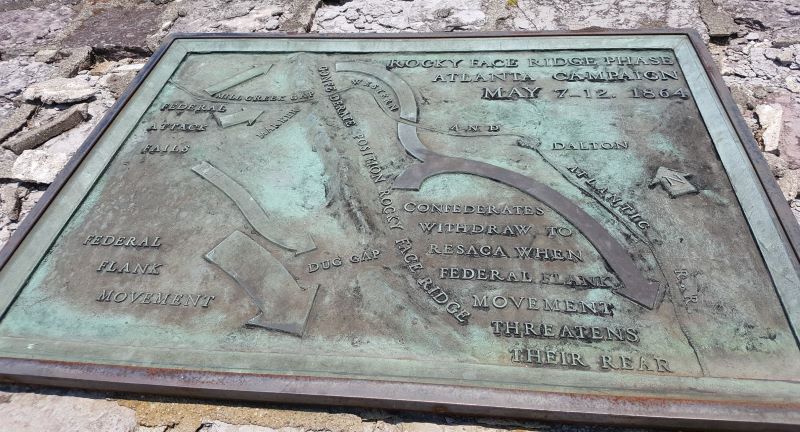

Johnston was well aware that he was outnumbered, and instead of taking any sort of offensive action as the officials in Richmond encouraged, he instead planned to build defensive fortifications on solid topographical positions and wait for Sherman to attack him. Rocky Face Ridge to the north and west of Dalton was the ground he chose to wait upon. The ridge, 800 feet high in some places, is marked by two gaps. The first, just northwest of Dalton, was Mill Creek Gap – also called Buzzard Roost. The second was southwest of the town and three miles south of Mill Creek Gap, called Dug Gap. The Confederate defensive line stretched for seven miles along Rocky Face Ridge, and by all accounts, it was the ideal position.

On February 25th, Thomas attempted an assault along Rocky Face Ridge and nearly succeeded until Johnston called reinforcements to bolster the line. Scouting further south, Thomas discovered Snake Creek Gap, which was nearly undefended. He proposed the idea of flanking Johnston’s line from this vantage point, as well as sweeping east to cut the Western & Atlantic Railroad to disrupt the Confederate supply lines. The maneuver would be executed in the first week of May and hit off the Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

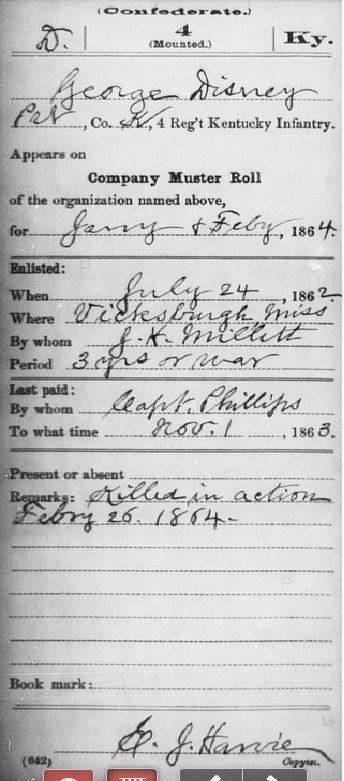

However, the event of significance to justify my climb up Rocky Face Ridge around Mill Creek Gap took place prior to Sherman’s replacement of Grant and months before he’d begin his flanking actions in May. George Disney, a native of England, first enlisted with the 1st Kentucky Infantry, Company G, on June 1, 1861, mustering in Owensboro, Kentucky.[1] When the company disbanded in the summer of 1862, Disney reenlisted with the 4th Kentucky Mounted Infantry, Company K, in Vicksburg Mississippi, July 24th, 1862.[2] Disney became a hardened veteran of the famed “Orphan Brigade” through numerous actions, including combat at Vicksburg, Baton Rouge, Stones River, Jackson, Chickamauga, and Missionary Ridge.[3] Now at Rocky Face Ridge, his regiment was under the leadership of Brigadier General Joseph Lewis within Major General William Bate’s division.

In February, the 4th Kentucky had been deployed in such a way as to form a “living telegraph line” from the valley next to Dalton to the very top of the ridge. From this point, the Federal line was well within full view of the Confederates atop the ridge. The purpose of the “living telegraph line” was so “when the Federal would move, word was passed from man to man.” Private George Disney was placed near the very top of the ridge, just one member of this communication chain. On February 25th, Thomas’ assault came on the right of the Confederate line and this unique method of communication was implemented. That night, the Confederates slept in their places, including Disney.

The story of Disney’s death, claimed as “killed in action” on his February muster roll, is detailed by the regimental history of the Orphan Brigade:

“The next morning George Disney, a private of Company B, arose to a sitting posture, after a night’s sleep on the top of this height in the open air, and was in the act of gaping, as many men are wont to do on first waking. He was seen suddenly to resume his recumbent position as though resolved to take another nap; but after he had been so lying for an hour or two, men who tried to wake him found that life had departed. A careful examination at the time disclosed no wound, and it was conjectured that he had died from failure of the heart or other disease. Later, another examination was made, and while washing the face of the corpse, the hair on the back of his head was found stiff from clotted blood; and it was then clear that while gaping a minie ball from a Federal musket in the valley in front had entered the open mouth and crashed through the back of the head of the unfortunate soldier.”[4]

He was buried where he had incurred this peculiar shot, at the top of Rocky Face Ridge.

His grave was rediscovered in March of 1912 by the local Dalton Troop of Boy Scouts. The wooden headboard was replaced by one of marble during a formal ceremony, complete with speeches and singing.[5] This headstone had been vandalized over the years, the pieces of which have been lost on the side of the mountain, leaving only an oblong pile of stones to mark the place where George Disney had died and been buried.

Because of the lack of any definitive marker, I almost disregarded the pile of rocks as something inconsequential. After all the sweat and work I put into climbing Rocky Face Ridge, I half expected something spectacular at the end of the trail. Instead, I passed by the grave completely and came to a clearing with rows of benches and an overlook area with some inspirational graffiti. I can only assume that another expeditionary group of Boy Scouts had

recently clamored their way up the “most challenging short trail” to leave their mark on the boulders that loom down over the valley. We eventually did backtrack to the gravesite and took the picture. In the end, my reward for the arduous hike was not a grand monument, and something equally impactful.

In the moment, exhausted and lightheaded as I was, I could only marvel at the resiliency of the common Civil War soldier. It’s one thing to read about their movements on the page, but to follow in their footsteps adds another level of understanding to their experience. As one treks up the mountain, a cool breeze comes infrequently because of the buffer of trees and foliage. This might not have been as important during the winter – such as George Disney would have experienced – but it was a godsend during the hot Georgia summer. At some points, the trail was so steep that slipping on the smoother rocks or missing a foothold added to the challenge of the hike. How many soldiers would have slipped during their march to their appointed station? Did frost or rain make the trek even more dangerous? How many nearly tumbled down the ridge? During the fall and winter months, when the trees near the peak are bare, the unimpaired view must be even more stunning than in the summer. Did the men 157 years ago stop and stare in awe as I did? Was George Disney impressed by the sights?

I climbed the mountain on purpose, but the men who fought at Rocky Face Ridge – and every other mountain for that matter – had no choice. They either defended it or attacked it, traversing those steep and jagged slopes, probably much easier than I did. Reflecting on my hike to George Disney’s grave, I have no regrets.

—-

Footnotes

[1] Compiled service record, George Disney, Private, Company G, 1st Kentucky Infantry; Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations , compiled 1903 – 1927, documenting the period 1861 – 1865, record group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[2] Compiled service record, George Disney, Private, Company K, 4th Kentucky Mounted Infantry; Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations , compiled 1903 – 1927, documenting the period 1861 – 1865, record group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[3] Edwin Porter Thompson, History of the Orphan Brigade, United States: L.N. Thompson, 1898, p. 688

[4] Ibid, pp. 238-239

[5] “Boy Scouts Do Honor to Confederate Dead,” The Chattanooga News, Chattanooga, Tennessee, May 13, 1912

References

Davis, Stephen. A Long and Bloody Task: The Atlanta Campaign from Dalton through Kennesaw Mountain to the Chattahoochee River, May 5-July 18, 1864. California, Savas Beatie LLC, 2016,

Thank you for sharing your fears and how you overcame them. Well done.

No question that’s a tough trail. But rewarding when you get to the top.

Wonderful post! Thanks Sheritta.

Yes, well done. That’s one heck of a shot that toppled old George. I wonder how far out the Yankee was. Sounds like a modern piece of marksmanship. It’s a shame someone hasn’t placed another military type headstone for him. Perhaps make it out of granite this time to give the vandals a bit more trouble in disposing of it.

I believe there are some plans in the hopper for creating a new headstone for Disney. The difficult part is lugging something made of such a heavy material up that mountain. Even then, there’s no guarantee that it’ll remain in tact with the frequency of hikers and boy scouts, and no way to monitor the preservation. In that case, anyone who may fund for a new headstone may be pouring their money down the drain.