Under Fire: A Bullet and Blood at Bull Run

A bullet striking a comrade standing just a few feet away introduced a Maine soldier to combat’s realities.

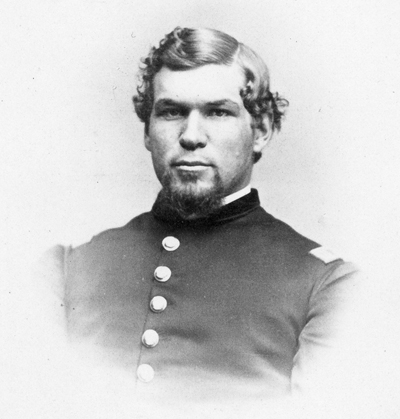

A 22-year-old college student when Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, Frank Lindley Lemont grew up on the Lewiston farm owned by his parents, Samuel and Jane Lemont. He enlisted on April 29 as the first sergeant in Co. E (Capt. Emery W. Sawyer), 5th Maine Infantry Regiment.

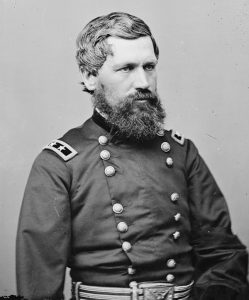

Coalescing at Camp Preble near Portland, the 5th Maine mustered into federal service on June 24 and entrained the next morning for Boston and ultimately Washington, D.C. The War Department assigned the regiment to the 3rd Brigade recently given Col. Oliver Otis Howard; part of Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman’s 3rd Division, Howard’s brigade included the 3rd Maine, 4th Maine, 5th Maine, and 2nd Vermont.

Commanded by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell, the Army of Northeastern Virginia marched out to fight Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and his Confederates at Manassas and Saturday night, July 20 found Howard and his brigade camped near Centreville.

“At Brigade inspection that night,” Howard “wished all to join in prayer for our welfare and the success of our arms,” Lemont said. “He joined with our Chaplain, and the whole Brigade uncovered their heads.”

“I did not know as ever I should behold another sun go down,” he admitted.

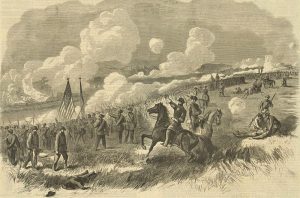

Lemont “awoke at the long roll” Sunday morning. Heading out the Warrenton Turnpike “past eight o’clock,” the 3rd Brigade swung onto a road leading to Sudley Ford and halted in reserve until 2 p.m., when McDowell’s chief engineer, Capt. A. W. Whipple, ordered Howard forward.

“It was one of the hottest days of the season,” but while “hundreds of stalwart fellows fell out on all sides” as the brigade double-quicked toward the ford, “I kept on hardly feeling fatigued,” Lemont said. Cannons boomed, and “we could hear the cracking, snapping sound of Light Infantry” charging enemy batteries.

After the brigade crossed Bull Run, near Sudley Church “our course was obstructed by the ambulances, filled with the wounded mangled in every shape,” Lemont recalled. “We passed along … trampling over the wounded … until we came to an opening directly in range of the Rebel guns.

“We passed nearly a quarter of a mile by the flank with the six pound shots whizzing just over our heads and falling all around us,” he said. “Still but very few of our men fell in this movement.”

Around 3 p.m. another McDowell aide steered Howard and his brigade southwest down Matthews Hill, past the Dogan House, and across the Warrenton Turnpike and Young’s Branch to support an artillery battery. “We … passed down into a hollow under the cover of a hill, but the shot and shell were thick,” Lemont said. “By the time we got to this place the most of the men had deserted us either through fatigue or” perhaps cowardice.

“Suffice it to say we had but eight men in our company ready to go up over the hill beside Lieut. [Aaron S.] Daggett and myself,” Lemont remembered.

Howard arranged his brigade in two lines: up front, the 4th Maine on the right and the 2nd Vermont on the left, and behind, the 5th Maine on the right and the 3rd Maine on the left. As the regiments waited in the ravine, “a shot sped by and struck a fellow [about three feet away] in the forehead[,] killing him almost instantly,” Lemont said. “I shall never forget the sound the bullet made as it struck him. He fell upon his back, threw up his arms, trembled slightly and was dead. He was the first man I saw killed that day.”

After advancing his first line up Chinn Ridge, Howard brought up his second line, the 5th Maine already partially stampeded by “a cannon shot striking its flank” and by retreating Union cavalry, he noticed.

Moving through “a thick growth of scrubby oaks and firs,” the 5th Maine “came out upon a broad opening” and, with the Vermonters moved into reserve, formed on the 4th Maine’s right flank. “I stood my place in the company while they discharged 8 or 10 rounds and [I] discharged my pistol once,” Lemont said. “But I was unharmed and received not even a scar.”

“It was a hot place,” Howard admitted. “Every hostile battery shot produced confusion,” and “soon the [line] breakages were beyond repair.” Men drifted backwards; officers could not hold their formations together.

“Our regiment retreated in the same manner that it went up, except that they did not keep together after a short time, all breaking up and mixing with other troops,” Lemont said.

He and Daggett retreated together. Suddenly “we heard a rushing sound of air, and … a shell burst just above our heads, and for a few seconds the pieces flew lively,” Lemont said.

As the Mainers reached high ground, Lemont looked back and saw Confederate infantry approaching the turnpike. “Lost in the grandeur of the spectacle,” he watched “their banners wave and the glittering of their bayonets in the sun.”

Then he realized the Confederates “were almost upon us,” and he and Daggett ran “as fast as our weary legs would carry us.”

Sources: 1860 U.S. Census for Lewiston, Maine; Frank L. Lemont Soldier’s File, Maine State Archives; Frank L. Lemont letter to Samuel Lemont, Lewiston Daily Evening Journal, August 12, 1861; Oliver Otis Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General United States Army New York, NY 1907), 159; Brian F. Swartz, Maine at War, Vol. 1: Bladensburg to Sharpsburg (Brewer, ME 2019), pp. 30, 44

McDowell, Howard AND Heintzelman as his commanders! God, grant him mercy!????