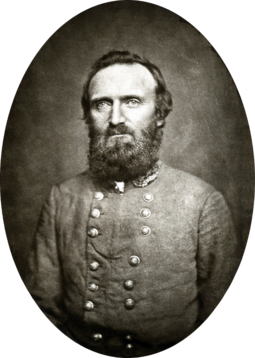

The Romney Expedition: Stonewall Observed

How did Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson experience the cold and storms during the Romney Expedition? Did it contrast with the experiences of his men? What did they observe in their leader?

This post shares some of those accounts while Part 3 will take a closer look at the leadership decisions and challenges Jackson faced (or created) on his march to Romney.

Jackson was a visible leader, and that was no exception during his winter march. At least on one occasion he put boots on the ground to help maneuver cannon or wagons along the icy mountain roads. John O. Casler of the 33rd Virginia recalled that on a particularly bad, icy day “General Jackson [got] down off his horse and put his shoulder to the wheel of a wagon to keep it from sliding back.”[i]

Mary Anna Jackson wrote after her husband’s death and after the war’s end about the expedition, pointing out: “The sufferings of the troops were terrible, as the frozen state of the roads rendered it impossible for the wagons to come up in time, and for several nights the soldiers bivouacked under the cold winter sky without tents or blankets. All these hardships and privations Jackson shared with the troops and tried to encourage them in patient endurance, and inspire them to press on.”

However, there were some privileges that Jackson enjoyed as the commander. One incident is a rare tale of Stonewall taking a swig of something stronger than lemonade:

The morning he started on this trip a gentleman of Winchester sent him a bottle of fine old whiskey. It was consigned to the care of one of the staff. As evening came on, it began to grow much colder, and it occurred to the General that a drink of wine—for such he supposed it was—would be very acceptable. Asking for the bottle, he uncorked it, tilted it to his mouth and without stopping to taste, swallowed about as much of that old whiskey as if it had been light domestic wine. If he discovered his mistake he said nothing, but handed the bottle to his staff, who, encouraged by the dimensions of the General’s drink, soon disposed of all that he had left. In a short while the General complained of being very warm, although it was getting colder, and unbuttoned his overcoat and some of the buttons on his uniform. The truth is, General Jackson was incipiently tight. He grew more than usually loquacious, discussed various interesting topics and among them the sudden changes of temperature to which the Valley is liable.[ii]

On the same night that some of his men bivouacked in the snow and wished the Yankees in the fiery underworld, Jackson had found shelter in “a very small log house.” Crowded into a small room with his staff officers, “they neither felt like talking nor going to bed” probably the effects of a cold and rather miserable day.

While in this charming social state, someone asked if there was no readable book in the party. Sandy Pendleton said he had Charles Lamb, whereupon he was requested by the staff to read the famous essay on roast pig. Being a good reader, Sandy gladly consented…. As the reader proceeded, the irresistible humor of it elicited smiles and laughter from all but the General. He said nothing but sat looking into the fire, as if unconscious that anything was being read in his presence. “The wind was raving in turret and tree,” but Sandy seemed to have forgotten it until he was suddenly interrupted by General Jackson. “Captain Pendleton, get your horse and ride to General Winder and tell him, etc.” General Winder was three or four miles distance and one can imagine what a miserable ride Pendleton had on such a night, and in such a country. When he departed no one had the courage to finish the essay.[iii]

Exactly what Pendleton the preacher’s son might have muttered under his breath that freezing night is anyone’s guess, but as the expedition pressed on through the mountainous region, the disgruntled soldiers were less secretive about their annoyance with their commander.

According to famous writer Sam Watkins who participated in the campaign, morale plummeted and men blamed Jackson. “The soldiers in the whole army got rebellious—almost mutinous—and would curse and abuse Stonewall Jackson; in fact, they called him “Fool Tom Jackson.” They blamed him for the cold weather; they blamed him for everything, and when he would ride by a regiment they would take occasion, sotto voice, to abuse him, and call him “Fool Tom Jackson,” and loud enough for him to hear. Soldiers from all commands would fall out of ranks and stop by the road side and swear that they would not follow such a leader any long.”[iv]

Though some memoirists blamed the weather, others who had been in the ranks claimed that Jackson called off campaigning beyond Romney due to the spirit of his troops. The feelings of the soldiers and their officers brewed a situation that Jackson would have to deal with in Winchester and by letter with the Confederate government in the weeks following the official period of the expedition. The Romney Expedition and its fallout set a less than stellar stage for Jackson’s start of the Valley Campaign in March 1862. (These details will be explored in the next blog posts.) Dividing his troops at Romney, Jackson left General Loring and a few thousand troops at that city and then ordered his Stonewall Brigade and most of the cavalry back to Winchester.

On January 21, 1862—his 38th birthday—Jackson headed for his headquarters town. Stonewall ended the campaign with personal enthusiasm and his staff protested on the road to Winchester. Once he had decided to return to his Winchester where his wife waited, Jackson rode forty-three miles in one day. His staff began to suspect his desires. Finally, one of them called out: “Well, General, I am not anxious to see Mrs. Jackson as to break my neck keeping up with you! With your permission, I shall fall back and take it more leisurely!”[v] Jackson apparently had no objections and continually his solitary gallop to Winchester. Arriving, he stopped at the Taylor Hotel to change or clean his muddy uniform, then headed for the Graham’s house where Mary Anna was staying.[vi]

Jackson believed his winter campaign had been successful, and his wife was surprised and delighted at his sudden return. Though the coming days would pass other judgement on his Romney Expedition, at least on his birthday, Jackson enjoyed thoughts of success and time in the domestic scene.

To be continued…

Sources:

James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, Macmillan, 1997).

Robert Lewis Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, Reprinted, (Harrisonburg, Sprinkle Publications, 1983).

[i] John O. Casler, Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, (1906). Page 63.

[ii] Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode With Stonewall, (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1968). Page 20.

[iii] Ibid., Pages 21-22.

[iv] Sam R. Watkins, Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War, (New York, Macmillan, 1962). Page 16.

[v] James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, Macmillan, 1997). Page 314.

[vi] Ibid., Page 314.

Sarah, one of the best posts EVER! ?

Thank you, sir!

Sarah, one of the best posts EVER! ?