The Voyage of the Clotilda – Part 2

See Part 1

The Africans held at the Ouidah barracoons (temporary holding cells for captives slated for sale) that would board the Clotilda came from all walks of life and different tribes. The majority of them were from Yoruba, though many were also of the Hausa, Fon, and Nupe tribes. Each tribe held similar customs and traditions, such as the practices of scarification, tattoos, and teeth filing to denote their status in society. Men and women worked as merchants, traders, farmers, craftsman, fishermen, priests or priestesses, doctors, or other skilled artisans. Young teens were initiated into secret societies to signal their coming into adulthood and eligibility for marriage. Most practiced either polytheistic or animistic faiths, or were Muslim. One unfortunate aspect of their society also included slavery, and the export of Africans became so ingrained in their economy that even the prohibition of the international slave trade could not slow down the trafficking of black bodies from the continent. Slavery within African society was not based on race, but rather status, and was considered a temporary situation that did not hinder social mobility after their term of enslavement. Within their enslavement, Africans served in a variety of capacities based on their skillset and enjoyed limited freedoms, including being able to own property and live separately from their owners.

Their societies were complex, cultures rich with tradition, communities close, economies diverse, and the connection of family were – and still are – pivotal in African society. By European standards, however, Africans lived as “savages” and the paternalistic view of pro-slavery individuals rationalized that the institution was doing the Africans a favor by bringing them to America to make them civilized.[1] Many of the captives in the barracoons were either kidnapped by the Dahomey kingdom or were prisoners of the many wars and conflicts that plagued the African tribes in the area. Some had been taken by desperate individuals who were looking to exchange their loved ones in the barracoons and bring them home.[2] Those within the barracoons would have had some difficulty communicating with one another, due to their distinct languages, though some traders were multi-lingual and became translators. Temporary bonds of friendship would have formed amongst the strangers in the barracoons as the captives tried to cope with their situation.

The 125 Africans that Captain William Foster hand-selected and purchased for $9,000 in gold and goods, ranged in age from 15 to 30, and were as varied as African society itself. Their names – Gumpa, Zuma, Kanko, Osso, Jabba, Kupollee, Kossola, and Abile – had meanings that told a story in their respective languages. For example, Kossola meant “my children do not die any more,” suggesting that his parents experienced the loss of children before him.[3] Other names denoted what season or day of the week a child was born. Soon, these names would be their only remaining connection to Africa. In an effort to minimize vermin, their colorful clothes were stripped from them, and all hair shaved from their bodies as they were prepared for sale.

On May 24, 1860, ten days after their arrival to Ouidah, the Clotilda was ready to leave Africa with its new cargo. However, another Portuguese ship on the horizon spooked Foster and the loading was hastened, ultimately leaving 15 Africans on the beach.[4] The Middle Passage, as it is commonly referred to, sent the remaining 110 Africans in the hold of Clotilda into a world of uncertainty and hardship. The space, only twenty feet wide and five feet high, left the naked Africans crowded and cramped. The Africans, unaccustomed to ocean travel, might have experienced sea sickness, as well as receive injuries from the rolling of the ship as bodies collided with one another. Wounds and open sores from rubbing the rough wooden planks or chafing from the chains that bound them together would have also caused great discomfort. Luckily, none became seriously ill – despite sitting in their own filth during the voyage – because Foster did not have a physician onboard. They were brought on deck after thirteen days in the cargo hold and took their first breath of fresh air since they left Africa. Many of them had to be carried on deck because they were too weak to stand or walk. For the rest of the trip, the Africans spent a great deal of time on deck and were highly observant of the crew and their surroundings. The most common complaint from the survivors was the general lack of water provided to them.[5] Despite historical mortality rates reaching 16% in the 1850s, no African on the Clotilda perished during the voyage.[6]

The journey back to Mobile took forty-five days and the Clotilda Africans remembered seeing the water change color as they entered the Gulf of Mexico. Before the Clotilda sailed into Mobile Bay, the crew mutinied again. Once more, Foster plied them with the promise of more money. On July 8, they were tugged by one of Meaher’s steamboats up the Spanish River toward Twelve Mile Island where the Africans were transferred from the schooner to another steamboat that would take them up the Tombigbee under cover of night. From there, they were brought to the confluence of the Tombigbee and Alabama River near Burns Meaher’s plantation, where they would be parceled out to the buyers who had made agreements with Timothy before the voyage.

Originally, it was planned that the Clotilda would be cleaned and modified again to resume her previous work, but the evidence left behind by the Africans in the cargo hold was too much. Foster took his ship upriver to Bayou Canot, about twelve miles northwest of Twelve Mile Island, and set it ablaze. The ship was not destroyed completely and during low tide, the remains could be seen for decades afterward.[7] The crew of the Clotilda, ready to receive their promised pay, were taken onto the Roger B. Taney with Timothy Meaher. They were given alcohol and stashed away in a secluded part of the ship so they couldn’t interact with paying passengers in route to Montgomery. When they arrived in Montgomery, to prevent the crew from spilling the beans about what they had just accomplished with the Clotilda, they were quickly transferred to a mail-train headed North with only about $600-$700 each, their original promised pay.[8]

The news of the Clotilda spread without the help of the cheated crew, as the story showed up in newspapers from New York to New Orleans, some exaggerating the details of the voyage and the Africans themselves. As a result, legal action was taken against key figures in the expedition. Timothy Meaher and William Foster were both tried and acquitted of any charges against them for import tax evasion and smuggling Africans onto American soil, as there was no evidence to convict them, besides the Africans whom officials could not find.[9] Ironically, when the Constitution of the Confederacy was drafted on March 11, 1861, Article I, Section IX stated, “The importation of negroes of the African race from any foreign country other than the slaveholding States or territories of the United States of America, is hereby forbidden.”[10] Therefore, Meaher’s actions would have also been considered illegal by the Confederacy as well s the United States. Meaher would go on to assist the Confederacy in blockade running along the Gulf Coast, sacrificing a few of his ships in the process.

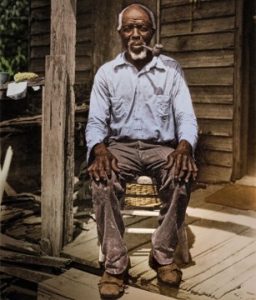

For the Africans who were sold to several planters in Alabama, they had experienced one tragic separation after another before enduring American slavery until 1865 at the conclusion of the Civil War. Not only did they have to learn English and adjust themselves to American customs, but they would also endure racism for decades following the war during Reconstruction and Jim Crow. Their hopes of returning to their homes in Africa would never be fulfilled. Instead, they made a new home just outside of Mobile.

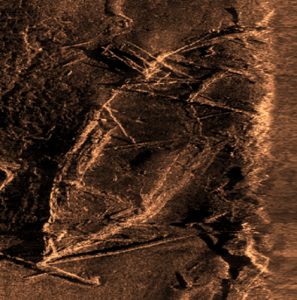

Through a group effort of Africans remaining in the Mobile area, land was purchased and the community of Africatown was born. Since 1870 when the first parcel was purchased, the descendants of the Africans from the Clotilda have kept their heritage and history alive, despite encroaching industrial development. The Clotilda Descendants Association, founded in 1984, has paved the way in public education about the Clotilda and Africatown. A heritage center, complete with a museum to tell the story of the Clotilda Africans, is currently in construction and predicted to be completed in 2022. The remains of the Clotilda were discovered in 2018 near Twelve Mile Island by journalist Ben Rains. According to specialists, it may be possible to salvage DNA from the wreck.

Since its discovery, a sonar image of the hull has been produced, revealing the evidence the courts lacked in 1860.

Endnotes

[1] Sylviane A. Diouf, Dreams of Africa in Alabama: The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Story of the Last Africans Brought to America, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 31-33; Daniel Walker Howe, What God Hath Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848, New York, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 58

[2] Slyviane A. Diouf, “The Last Resort: Redeeming Relatives and Friends,” in Diouf ed., Fighting the Slave Trade, pp. 81-100

[3] Herbert S. Klein, The Atlantic Slave Trade, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999 p. 199

[4] Emma Langdon Roche, Historic Sketches of the South, New York, Knickerbocker Press, 1914, p. 99

[5] Diouf, Dream of Africa, pp. 62-66

[6] Ibid, p. 64

[7] Ibid, p. 75

[8] William Foster, “Last Slaver from U.S. to Africa. A.D. 1860,” Mobile Public Library, Local History and Genealogy, p. 12; “Last Cargo of Slaves” Saint Louis Globe Democrat, November 30, 1890; Roche, Historical Sketches, pp. 85, 97; Henry Romelyn, “Little Africa,” The Southern Workman 26, I, January 1897, p. 15; Samuel Hawkins Marshall Byers, “The Last Slave Ship,” Harper’s Monthly 113, 1906 p. 746

[9] Diouf, pp. 79, 87

[10] James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, Including the Diplomatic Correspondence 1861-1865, Nashville : United States Publishing Company, 1905, [Online access: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/csa_csa.asp]

As revealed in the above report, the captain of the Clotilda, William Foster, knew “exactly where to go” in order to acquire his African bondsmen direct from the source… in spite of the import into America of slaves from Africa having been illegal since 1808. And in spite of British patrols of the African coast, augmented by the occasional U.S. Navy vessel, on station to enforce the prohibition of the slave trade.

In a report delivered to Congress in December 1859, published on pages 5 and 6 of the attached Alexandria Gazette, President Buchanan addressed the Prohibition of the Slave Trade (all of column two, page 5) and expressed his belief that, “the Acts of Congress initiated, with very rare and insignificant exceptions, have achieved their purpose.” Yet, just a few lines later, the President admits: “…when a market for African slaves shall no longer be furnished in Cuba, and thus all the world be closed against this trade, we may then indulge a reasonable hope for the gradual improvement of Africa.” No wonder the Knights of the Golden Circle wished to incorporate Cuba into their Slave Empire. And in the meantime, the U.S. Navy (size of force determined by Congress) possessed so few ships that its captains moonlighted on Mail Steamers, and its patrol of the African coast was little more than a token effort. Alexandria Gazette of 19 DEC 1859 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1859-12-19/ed-1/seq-5/

Thanks again to Sheritta Bitikofer for providing an excellent, compelling report.

And thank YOU for sharing those extra bits about the illegal slave trade. There was another ship caught in 1864 called the Mary that was trying to bring Africans to Georgia. I’m hoping to look into the court case around its capture.

Thank you for sharing this research, Sheritta. It is hard to read because of the subject, but you wrote about it in a very honest and touching way.