The Battle of Memphis and Its Fallen Federal Leader

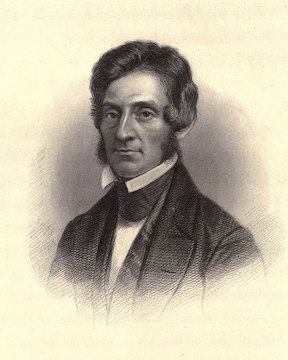

One of the most consequential battles of the war—and one of the shortest—took place on June 6, 1862: the battle of Memphis. Federals suffered only a single casualty, Col. Charles Ellet, Jr., the man most responsible for the victory in the first place. Although he would not die immediately, Ellet would not live long enough to see the incredible fruits of the victory he helped make possible.

A Pennsylvania native, Ellet was an engineer by trade. He designed and oversaw construction of the first cable-suspension bridge in the U.S., a 358-foot span over the Schuylkill River north of Philadelphia. (He’d originally pitched one for the Potomac River but was turned down.) His bridge building got bigger. Subsequent bridges in Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia) and Niagara Falls, New York, measured more than 1,000 feet and 750 feet, respectively.

Ellet also worked on flood control studies along the Mississippi whose long-term impact would make him a one-man TVA. Earlier biographer Gene D. Lewis says, “Ellet’s interest thus ranged broadly from bridge-building, canal and railroad construction, and the economics of transportation to the improvement of western rivers, and to projects for defeating the Confederacy.”[1]

A fluke accident led to what became his most important impact on the Civil War. While traveling overseas in the mid 1850s, Ellet heard tell of a paddle-steamer, the USS Arctic, that was accidentally sunk by a much, much smaller ship, the propeller-driven USS Vesta, which had run into the Arctic. The Arctic was 11 times bigger than the Vesta. The incident convinced Ellet that a steam-powered ship like the Vesta could, with enough momentum, effectively serve as a ram that could literally batter opposing ships into sinking.

Ellet came from deep Revolutionary stock: both grandfathers served in the American Revolution. Although his own father was a Quaker, a sect known for the pacifism, Ellet felt compelled to do his part when war broke out in 1861. He tried to get someone—anyone—in the army or navy to listen to his ideas about rams, and finally, in early 1862, he found a receptive audience in Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

On March 20, 1862, Stanton summoned Ellet to a meeting of Stanton’s top army advisers to make his pitch. After, Quartermaster Montgomery Meigs admitted Ellet “might be usefully employed by the government in gunboat construction in the west.” Stanton did Meigs one better. “Perhaps he would be as good a man as we could get for that purpose,” the secretery replied, adding:

He has more ingenuity, more personal courage, and more enterprise than anybody else I have every seen. . . . He is a clear, forcible, controversial writer. He can beat anybody at figures. He would cipher anybody to death. If I had a proposition that I desired to work would to some definite result, I do not know of any one to whom I would intrust it so soon as Ellet. His fancy and will are predominant points, and once having taken a notion he will not allow it to be questioned.

“Is there any better person to whom I could commit that duty?” Stanton concluded.[2]

When informed of his new assignment, Ellet was delighted. He asked if it would be possible to be placed outside the chain of command, ostensibly because of his lack of military experience. Under factor may have been that he did not want to serve under Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who’d spurned his suggestions for a year and a half before Stanton had taken notice. However, as Stanton pointed out, Ellet as a civilian would be legally ineligible to command any of the ships. Therefore, the secretary countered with an offer to make Ellet a colonel with a direct report to the secretary of war. Furthermore, Ellet would command the ram fleet directly, although the fleet itself—when it finally took to the water—would fall under the operational command of Flag Officer Charles H. Davis. This unconventional command structure seemed to suit Ellet, who anticipated action “not in accordance with naval usage.”[3]

Stanton instructed Ellet to start work in three places— Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and New Albany—to “bring out the whole mechanical energy of the Ohio Valley.”[4] The plan was “to take the largest and most powerful river boats, remove the upper works, fill the bows with timber, and furnish such protection as can be afforded. . . .” One of Stanton’s advisers suggested iron plating for the rams, but Stanton nixed the idea. “We do not want to wait for iron armor,” he said. “Ellet calculates upon destroying a boat right off by running into her.”

Work on the ram fleet progressed smoothly and quickly. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, just then setting his sights on the Confederate supply base at Corinth, Mississippi, expressed anxiousness about threats to his own supply line, in particular “ironclad boats now being built at New Orleans, to be sent up the river for the purpose of interfering with our flotilla.” What was “the proper way to meet these boats?” Halleck inquired.[5]

The answer was the ram fleet. Ellet envisioned a fast and decisive strike down the Mississippi. “What we do with these rams will probably be accomplished within a month after striking the first boat . . .” he wrote. “I think if I can get the boats safely below Memphis I can command the river.” He did worry about the river batteries at Memphis and believed that he’d have to run the rams past them; once below the city, they would be unable to return and must either “go down the Mississippi or be sunk or taken.”[6]

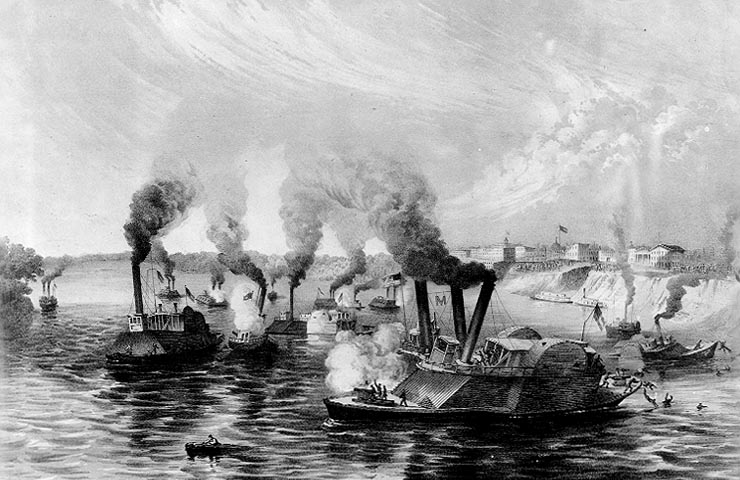

Ellet’s boats rendezvoused and, with Ellet in command of The Queen of the West, they began their movement downriver—even as word arrived of the Confederate fleet moving northward to meet them. The forces, when they clashed, would be closely matched: Federals had nine vessels; Confederates eight.

The two forces met around 5:30 a.m. on June 6, 1862, on the edge of Memphis, Tennessee. “Rebel gunboats made a stand early this morning opposite Memphis, and opened a vigorous fire upon our gunboats, which was returned with equal spirit,” Ellet wrote.[7] Davis ordered the Federal armada in at full speed, with the ram fleet in the lead. “The rebel rams endeavored to back downstream and then to turn and run, but the movement was fatal to them,” said Ellet.

Ellet’s Queen of the West opened the battle by ramming the Confederate flagship, CSS Colonel Lovell. “My speed was high, time was short,” Ellet said, picking the Lovell as the easiest of three targets that had, in the midst of turning around, presented their broadsides to the rams. The Queen hit just forward of the Lovell’s wheelhouse. “The crash was terrific,” Ellet said. “Everything loose about the Queen—some tables, pantry ware, and a half-eaten breakfast—where overthrown and broken by the shock. The hull of the rebel steamer was crushed in, her chimneys surged over as if they were going to fall over on the bow of the Queen.”[8] Ellet recalled “the surface of the Mississippi strewn with the fragments of the rebel vessel.”[9]

Less than half a minute later, though, the Queen herself was struck. A double-team by the CSS Sumter and the CSS Beauregard disabled her with a blow directly to the wheelhouse. “The blow broke her tiller rope, crushed in her wheel and a portion of her hull, and left her nearly helpless,” Ellet reported.[10] His ram drifted to the Arkansas shore with only one wheel and without a rudder, and there it grounded.

Shortly thereafter, another Federal ram—the USS Monarch, captained by Ellet’s brother, Alfred—disabled the CSS General Price, which ran aground not far from Ellet’s Queen. Ellet could not resist, and he sent a boarding party to the disabled Confederate ship. A flagship, after all, would make a fine spoil of war.

Confederates resisted the Federal attempt to board, though, and in the ensuing gunfight, a bullet clipped Ellet in the knee. The “pistol-shot wound in the leg deprived me of the power to witness the remainder of the fight.”[11]

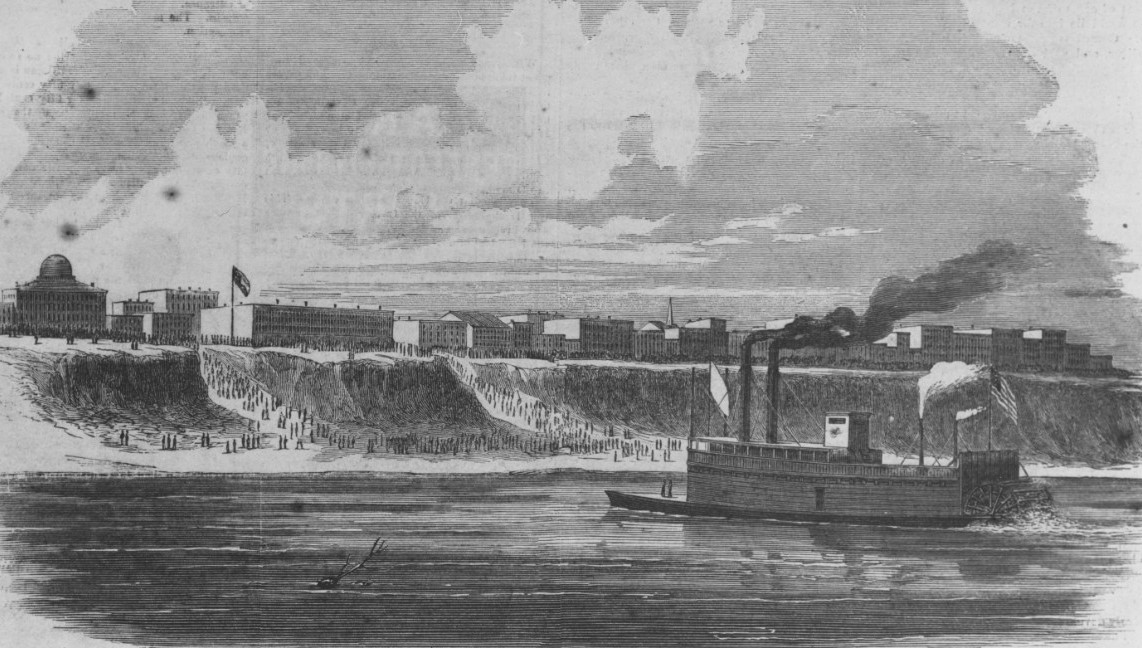

There were plenty of other witnesses to the fight, though: nearly the entire population of Memphis gathered on the bluffs overlooking the river to watch the spectacle unfold. Within ninety minutes, it was all over. “The enemy’s rams did most of the execution, and were handled more adroitly than ours,” said Confederate Gen. M. Jeff Thompson, who was among the crowd watching from the bluffs. “[A]nd I am sorry to say that in my opinion many of our boats were handled badly or the plan of battle was very faulty.”[12]

Memphis surrendered that afternoon. Ellet sent his son, Medical Cadet Charles R. Ellet, into the city with a pair of U.S. flags, one to fly over the customs house and the other to fly over the post office “as evidence of the return of your city to the care and protection of the Constitution.”[13] Ellet the Youngest was accompanied by members of the 59th Illinois Infantry. And a good thing, too: an “excited crowd, using angry and threatening language” fired upon the party and threw stones. Strong Federal patrols went into the city that evening to quell the public disquiet.

Stanton received news of the victory at Memphis on the evening of June 8. His elation was “dampened only by your personal injury,” he wrote to Ellet. The secretary personally assumed the duty of telling Ellet’s wife, Elvira (called “Ellie”), the news about Ellet’s injury. “She was, of course, deeply affect, but bore the information with as much spirit and courage as could be expected,” Stanton reported. “It is her design to proceed immediately to join you.” Stanton furnished her to a pass for free passage for her and the Ellets’ daughter, Mary. “You will keep me advised of your state of health and everything you want,” Stanton added.[14]

What Ellet wanted was to continue his mission downriver. On June 8, as Stanton was penning his congratulations, Ellet was hoping to start southward with the ram fleet the very next day. Davis even offered to send a gunboat along with the rams. “Of course I will not decline,” Ellet said, “though I fear the slowness of the gunboat will impede the progress of my expedition.”[15]

Ellet was not looking a gift horse in the mouth. He had been pleased with the way Davis’s ships had supported the ram fleet. “Of the gunboats I can only say that they bore themselves as our Navy always does—bravely and well,” he wrote.[16] Davis, meanwhile, noted Ellet “was conspicuous for his gallantry” and believed Ellet’s wound serious but not dangerous.[17]

But the wound was more serious than anyone first imagined. Complicating matters, Ellet contracted measles during his convalesce. On June 11, as he wrote a follow-up report to the battle, he stopped midway through. The Official Records note Ellet’s report was discontinued “on account of Colonel Ellet’s exhaustion” and never resumed.[18]

On May 15, Ellie and Mary arrived from Philadelphia. Writing to Stanton on June 16, Ellet thanked him for sending them along. He also petitioned Stanton to place his brother, Alfred Ellet, in charge of the ram fleet in his stead. “The great prostration of my system points, I fear, to slow recovery,” the wounded colonel admitted. “I can do nothing here but lie in my bed in suffer.”[19]

Stanton, who received the letter on the 18th, complied with Ellet’s request two days later. Writing to Alfred, he said, “I regret that your brother’s illness deprives the Government of his skillful and gallant services, but have confidence that you will supply his place better than anyone else.”[20] The fleet started south the next day.

One of the fleet’s boats did not go southward, though. The USS Switzerland was tasked with transporting Ellet and his family northward to the army hospital in Cairo, Illinois. Ellet died as the ship reached port around 4 p.m. on June 21, 1862, in Cairo, Illinois. Quartermaster James Brooks informed Stanton of the news by telegraph.[21]

Ellet’s body was shipped back east where it lay in state in Independence Hall under the Liberty Bell. The Philadelphia City Council, grateful for Ellet’s role in the fall of Memphis, appropriated $500 to help defer funeral expenses, and Ellet was buried in the city’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. Unfortunately, Ellie, exhausted and overcome with grief, died within a fortnight and was buried with her husband.[22]

Ellet would not see the incredible impact his victory would have. Coupled with Grant’s victory on the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing and Halleck’s move from there toward Corinth, the fall of Memphis allowed Federal forces to advance against the Deep South. Memphis, in particular, would serve as the staging area for all future operations against Vicksburg, and by some accounts, more than a million soldiers would move back and forth through the city as part of those operations, swelling the city’s population and bringing economic prosperity.

Early Ellet biographer George Gorham credited the victory at Memphis to “the zeal and energy of two civilians”: “Stanton’s confidence in Ellet and the latter’s confidence in himself. . . .”[23] Indeed, Stanton said in March when he had approved Ellet’s plan for the ram fleet: “Mr. Ellet himself is willing to risk it.” Ultimately, Ellet risked it all. The verdict of history has been, in the words of one historian who captured the sentiments of many, that “few Northern triumphs in the Civil War were more complete or one-sided than the Battle of Memphis.”[24]

————

On June 6, 2020, ECW Naval Historian Dwight Hughes wrote an excellent post about the battle of Memphis, including background, details of the fight, and analysis of the results. Read Dwight’s post here.

Here’s a video I did from the banks of the Mississippi in Memphis to commemorate the anniversary:

I would like to offer my thanks to historian Curt Fields for taking me to the banks of the Mississippi in Memphis to show me the scene of the battle.

[1] Gene D. Lewis, Charles Ellet Jr., The Engineer and Individualist, 1810-1862 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 3.

[2] George Congdon Gorham, Life and Public Services of Edwin M. Stanton (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1899), 290, 292.

[3] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume XXIII, 74.

[4] Quoted in Gorham, 295.

[5] Gorham, 291.

[6] O.R., Vol. X Pt. 2, 112.

[7] O.R. 907.

[8] O.R. Vol. X, Pt. 1, 926.

[9] O.R., Vol. X, Pt. 1, 926.

[10] O.R. Vol. X, Pt. 1, 926.

[11] O.R. Vol. X, Pt. 1, 907.

[12] Quoted in Gorham, 299.

[13] O.R., Vol X, Pt. 1, 910.

[14] Quoted in Gorham, 299.

[15] O.R. Vol. X, Pt. 1, 907.

[16] O.R. 908.

[17] O.R., 907.

[18] OR. 927.

[19] O.R. LII, 257.

[20] O.R. LII, 258.

[21] O.R. LII, 258.

[22] Lewis, 207.

[23] Gorham, 299.

[24] Quoted in Lewis, 207.

I always wonder what the citizens of Memphis must have thought as they watched the destruction of the Confederate River Defense Fleet. It is sort of like a reversal of roles from 1st Bull Run with the DC picknickers.

Rule of thumb in physics: If you’re a ram, go with the river.

Informative and compelling report, exposing one of the few instances that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton revealed his “kinder, gentler side.”

He had one? LOL

Once again, the ECW has delivered an interesting piece on a strategic, important event little known or understood by this reasonably well-read Civil War student.

The title of the above article is appropriate for another reason, June 1862 seeing “the fall” of a second Federal officer at Memphis… but first, some background information. The newspaper-reading public, unschooled in the conduct and goals of war, gives undeserved credit to the “capture of territory.” In particular: the capture of a city, and the identity of the officer responsible for that achievement. During the Civil War, the public read that “Lyon saved St. Louis for the Union,” and “Buell took Nashville in February 1862.” Probably most famous, it was reported in 1864 that, “Sherman took Savannah, and presented that trophy as Christmas gift to President Lincoln.”

Before reading further, WHO was given credit for capture of Memphis?

As we know, Ellet was most responsible; and Colonel James Slack of the 47th Indiana was assigned as Commander, occupation force on or about 8 June 1862. But the first General officer to act as Military Governor of Memphis… was Major General Lew Wallace. Following Halleck’s Crawl to Corinth, and the occupation of that “most important of Confederate rail crossroads,” a pursuit of Beauregard’s retreating army was attempted, with Halleck providing real-time updates to Secretary of War Stanton, via the telegraph. After chasing the rebels as far south as Guntown Mississippi (37 miles south of Corinth) and with thousands of Rebels captured enroute (and many of those surrendering) Halleck determined that “The Rebel Army is disintegrating before our eyes; and what little remains is far enough away to the south to be unable to interfere with the next phase of operations.” On 8/9 June 1862, pursuit was called off, the Campaign for Corinth was declared a success, and Major General Halleck set about… rebuilding damaged Southern railroads for Federal use. In particular, William Tecumseh Sherman, John McClernand, and Lew Wallace were detailed territories in Northern Mississippi and Western Tennessee in which ALL of the rail lines were to be restored; and Major General John Pope was sent to St. Louis to contract for construction of railroad carriages to be put to use on those lines.

As reward for “service up to that point,” it appears that Halleck intended for newly-minted Major General W.T. Sherman to be assigned to Memphis as Military Governor; and Major General U.S. Grant, restored to command of what would become known as Army of the Tennessee, was to have his HQ in Memphis.

But, while in process of rebuilding railroads, MGen Lew Wallace received an urgent message from Colonel Slack at Memphis: “Intelligence indicates a force of several thousand rebel cavalry intend attack upon Memphis. Please send assistance.”

On 17 June 1862 Lew Wallace and most of his Third Division arrived in Memphis. Measures were put in place to fortify the city against the expected attack; and patrols were despatched south in attempt to locate the Rebel base. In meantime, Wallace established himself as Military Governor; he took steps to promote goodwill with Memphis residents (and, controversially “took control” of Confederate-supporting newspapers).

To continue… Shortly after arrival in Memphis, MGen Lew Wallace made use of the restored telegraph line connecting Memphis to Corinth and reported his location, and why he was there, to Major General Halleck. But Halleck did not reply. Instead, MGen John McClernand, immediate superior to MGen Wallace as Commander of the Reserve, contacted Wallace via the telegraph and “recommended” that Wallace might want to establish his HQ outside of Memphis, perhaps at one of the small towns just to the east. But, believing his current location was best for all concerned, Lew Wallace remained in Memphis.

Meanwhile, at his HQ in Corinth, Henry Halleck grew ever more irritated; Halleck “knew” that the Rebel Army to his south was disintegrating. And checking with MGen Sherman about the state of affairs along the Memphis & Charleston R.R. being restored by Sherman’s 5th Division, Sherman confirmed “there were no Rebels at Holly Springs [35 miles southeast of Memphis].” And Halleck possessed intelligence that indicated what remained of the Rebels that had fled Corinth had established their HQ at Tupelo Mississippi, 50 miles south of Corinth. As far as Halleck was concerned, Lew Wallace was ensconced in Memphis and using “phantom Rebels” as excuse to NOT restore railroads.

On 21 June 1862 Halleck despatched Major General Ulysses S. Grant “to sort out the situation in Memphis.” [Grant, in his Personal Memoir, claims that “he asked permission to establish his HQ in Memphis.”] Truth be known, there had been bad blood between Lew Wallace and U.S. Grant since the Fort Donelson campaign, when Wallace violated standing orders and sent elements of his Third Division to the assistance of John McClernand’s struggling First Division. In addition, Wallace was late getting to the battlefield during Day One at Shiloh, and General Grant was certain that Wallace had ignored simple, direct orders and taken the wrong road. Grant travelled light and his small force of mounted horsemen travelled fast and reached Memphis in the afternoon of June 23rd.

The exchange between Lew Wallace and U.S. Grant is a matter for conjecture: both men agree that “Lew Wallace was granted leave of absence to return home to Indiana to sort out personal matters.” And Wallace departed that very day. Grant selected Brigadier General Alvin Hovey as Acting Commander of the Third Division; and then that Third Division was systematically dismantled, with bits of it reassigned to McClernand’s First Division, some of it assigned to Sherman’s Fifth Division, and the remainder sent into camp south of Memphis (and eventually was re-branded as the Twelfth Division.) As Wallace reports in his Autobiography, “Secretary of War Stanton sent orders to the Governor of Indiana, assigning me to recruiting duty in Indiana… [and I discovered that] my Third Division had been broken up.” On this day in 1862, Lew Wallace departed Memphis on Leave of Absence, and his career with the Army of the Tennessee came to an end.