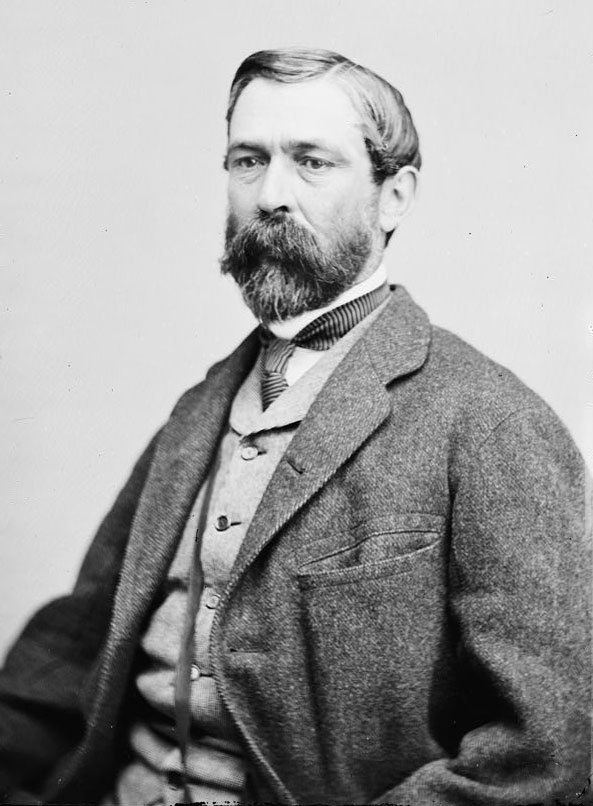

Richard Taylor on Stonewall Jackson

As we wrap up the 160th anniversary of Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, I want to share with you an observation made by Richard Taylor. Taylor’s Louisianans played a key role in several battles during the Valley Campaign and then traveled with Jackson’s army to Richmond to participate in events during the Seven Days.

Taylor’s service led Jackson to recommend him for promotion to major general. With the promotion came Taylor’s transfer to the Trans-Mississippi, which allowed Taylor to escape any potential future conflict with Jackson, which so many of Jackson’s subordinates seemed to struggle with over time. That allowed him to watch the rest of Jackson’s wartime performance from a safe distance.

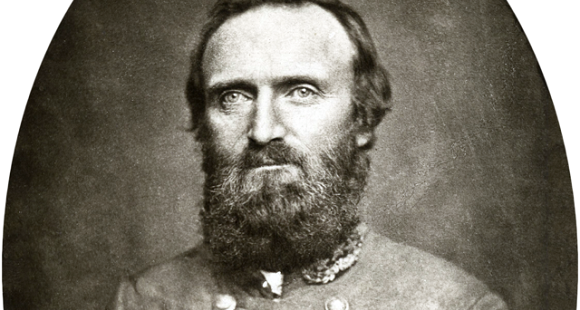

In 1879, Taylor published his wartime reminiscences, Destruction and Reconstruction. In the book, Taylor offered his assessment of Jackson, formed in the crucible of battle and cured over seven years and a thousand miles of distance. “Observing him closely, I caught a glimpse of the man’s inner nature,” Taylor claimed. “It was but a glimpse.” What he saw, he said, was “an ambition boundless as Cromwell’s, and as merciless.”[1]

Taylor continued:

I have written that he was ambitious; and his ambition was vast, all-absorbing. Like the unhappy wretch from whose shoulders sprang the foul serpent, he loathed it, perhaps feared it: but he could not escape it—it was himself —nor rend it — it was his own flesh. He fought it with prayer, constant and earnest — Apollyon and Christian in ceaseless combat. What limit to set to his ability I know not, for he was ever superior to occasion. Under ordinary circumstances it was difficult to estimate him because of his peculiarities—peculiarities that would have made a lesser man absurd, but that served to enhance his martial fame, as those of Samuel Johnson did his literary eminence. He once observed, in reply to an allusion to his severe marching, that it was better to lose one man in marching than five in fighting; and acting on this, he invariably surprised the enemy—Milroy at M’Dowell, Banks and Fremont in the Valley, M’Clellan’s right at Cold Harbour, Pope at Second Manassas.

Fortunate in his death, he fell at the summit of glory, before the sun of the Confederacy had set, ere defeat and suffering and selfishness could turn their fangs upon him. As one man, the South wept for him; foreign nations shared the grief; even Federals praised him.[2]

Taylor seemed to regard Jackson with a tense mix of admiration and skepticism, as though maybe he didn’t quite like him but felt compelled to respect him (my interpretation).

Taylor, it’s worth adding, provides one of the very few accounts of Jackson eating a lemon—a popular part of the modern Jackson myth. “Where Jackson got his lemons ‘no fellow could find out,’ but he was rarely without one,” Taylor wrote.[3]

————-

[1] Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (New York: Appleton & Co., 1879), 79.

[2] Taylor, 80.

[3] Taylor, 50.

Thanks for sharing this. His perspective is interesting, and I rather enjoyed his writing.

I also enjoyed his writing, and now want to read his memoir.

It’s interesting stuff!

Taylor’s book “Destruction and Reconstruction” is very good. Re Jackson, and Taylor’s opinion, ti would be easy to take that as a negative but as Taylor himself points out, Jackson’s goal was to win, while inflicting the least damage as possible on his own soldiers. “Ambitious” or not, his tactics were appreciated by the soldiers who followed him into battle. It’s easy to assume a fall from grace had Jackson lived, but that would be just that – an assumption, with no basis in fact.

Taylor obviously wrestled with a kind of ambivalence about Jackson that I’ve always found interesting.

I don’t think Jackson’s soldiers appreciated his tactics much until he started winning. There’s a lot of grumbling in the letters and diaries of the men during the Valley Campaign. Once he became a legend in his own time, THEN they liked him a whole lot more!

Richard Taylor most of have learned some things from Jackson’s Valley Campaign, because Taylor himself put in an aggressive, damage the enemy performance as the Wester District of Louisiana commander. Like Jackson, he was energetic and attack minded, failing and succeeding in turns. Like Jackson, he was outmanned and outgunned, yet looked to hurt his opponent whenever he could and also tried to take advantage of situations where the numbers might be in his favor.

Taylor might have been the most well rounded Confederate general at the end of the war other than R.E. Lee. Whereas Jackson was definitely capable of thinking big, Taylor was able to think big and small. Taylor understood the logistics needed to support an Army that could hit its opponent effectively, organizing a logistics network in his District himself, and he competently manage the smallest units during combat. He was able to understand the large strategic situation and was directing troop movements effectively over hundred of miles. He would have been an excellent Chief of Staff to any of the Full or Lieutenant Generals commanding earlier or mid-way during the war. He did suffer from rheumatism, could be tart with subordinates because of that or if he was disappointed in their performance, but he freely gave praise to those same officers and to the soldiers themselves even while recognizing and pointing out some issues they may have had. He also had to contend with riverine operations and was able to get some licks in there too. Very R.E. Lee like but without the engineering background.

That’s a good assessment of Taylor. Thanks for sharing it!

Well, it’s not a ‘myth’ to say that SWJ enjoyed lemons. He plainly did as even this piece of evidence shows. Robertson explained well in his massive biography that Jackson enjoyed ALL fruit. Service in Mexico had literally been akin to a child in a candy store for him in this regard.

He loved fruit; it was one of the few material pleasures he had a straightforward engagement with his whole life. He did enjoy lemons and lemonade in his zestful consumption of all fruits.

The association with them and him is not a ‘Popeye and Spinach’ type one that is often indicated. At the same time, there is more than enough evidence to substantiate that he had a zest for them.

If you read all of the American Heritage Dictionary’s sub-definitions of ‘myth’ all boiled down and taken holistically, a ‘myth’ is essentially one of two things:

1) What is commonly attributed to a figure/event/etc, can not be at least reasonably supported by the known, credible evidence.

2) What is unknown/unprovable about a figure/etc, etc, due to the lack of evidence is more important than what the known, credible evidence can actually bear at least a reasonably satisfactory testament to.

Since Jackson did enjoy lemons, it’s not accurate to describe this as a ‘myth’. His association with lemons has certainly been embellished, (like saying Abraham Lincoln did not possess physical strength from splitting rails and woodwork, that the amount of time he actually spent doing these activities was too little to accord him any status as a ‘Railsplitter’. His attendance at a field hospital near the end of the war, as cited in Vol. 4 of Sandburg’s ‘The War Years’, and his demonstrated ability with an axe), shows that this can not be be accurately called a ‘Lincoln myth’, either.