John Burns: The Cantankerous Neighbor

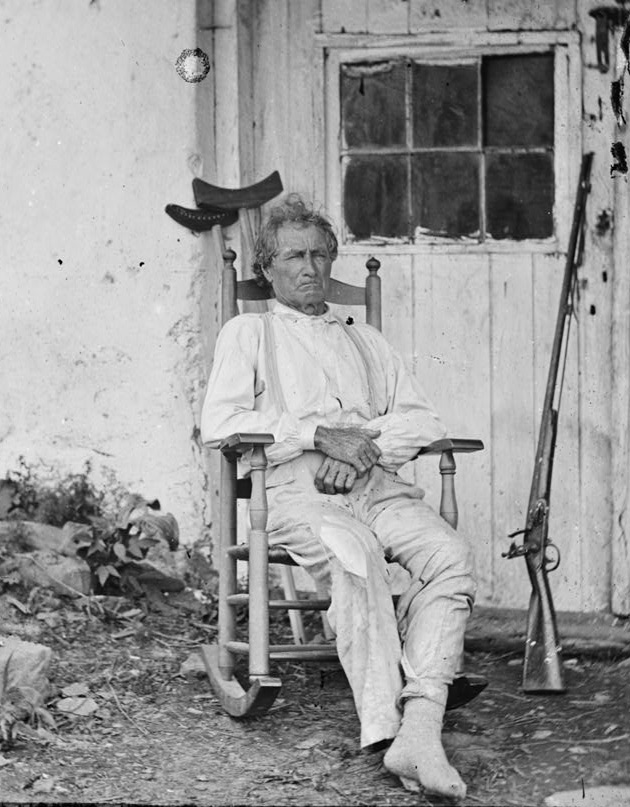

John Burns of Gettysburg seems to have several images in Civil War memory. The grim-looking fellow seated in a rocking chair when his photograph was taken. The old, oddly-dressed man who appears alongside enlisted Union volunteers with an ancient musket, wanting to take some shots at the Rebels. And the idea of a nice, elderly hero who walked with President Lincoln through the street of Gettysburg on the afternoon of November 19, 1863, as they went to a church to hear Charles Anderson’s address.

Most of those memory snapshots might have been unfamiliar to those who know John Burns in real life. Most of his neighbors didn’t have great things to say about him…until after he got famous (and some not even then!). There are so many stories and legends about Burns that it can be challenging to separate fact from fiction. For an in-depth study, check out Timothy H. Smith’s book, John Burns (2000).

Today, let’s take a little closer look at a few accounts of cantankerous fellow and his famous volunteerism during the first day of the battle of Gettysburg—July 1, 1863.

John Burns was 69 or 70 at the time of the battle. Different sources and storytellers give different ages, but he was an old fellow—that is agreed upon. He had been the local constable, but lost the position in the previous election which prompted him to take up a job as a cobbler at David Kendlehart’s boot and shoe manufactory.[i] A “teetotaler”, Burns had been known to pace around the town of Gettysburg in his previous days as a constable and if all was well, he liked to wander into the McClellan House Hotel to join the temperance meetings or talk with his neighbors.[ii]

Burns was married, and apparently, the marriage caused some talk before, during, and after the battle. It seems that all was not peaceful and harmonious in that household. For example, one version of the July 1 stories begins with Mrs. Burns exclaiming: “Burns, where are you going?” Presumably, the husband was putting on the blue coat or gathering his gun. “Oh, I am going to see what is going on.”[iii] What happened next isn’t quite clear. Some versions have Mrs. Burns following her husband to the door or even up the street, calling him an “old fool.” Or…maybe she just gave him the epitaph on his way out the door. From her actions a few hours later, it can be concluded she was not pleased with his battlefield adventuring at the very least and at the worst wished he would never come back.

Once outside the house — possibly with his wife still shouting at him — John Burns got into an altercation with his neighbors. According to William H. Tipton:

“We were standing opposite his home. John Burns became very abusive to Joseph Broadhead, a one-eyed neighbor of his, insisting on his getting a gun and going along and upon his refusal called him a ‘coward — a chicken-hearted squaw,’ and used language that I will not repeat here. Miss Mary Slentz hearing Burns, came out of her home next door and rebuked him for his abuse of Broadhead and advised him to stay home. When he started out he may have worn a blue coat, but we did not see it as he wore a long linen duster. He wore a high crowned felt hat.”[iv]

Alone, Burns headed for the sound of the rifle volleys on the ridges to the west of his hometown. What motivated him? Patriotism? Revenge? There are stories that he got particularly mad at the Confederate raiders on June 26. Just the need to get out of the house? The desire to prove or regain some war hero status in town or in the eyes of his wife? There are lots of versions of the John Burns story both on and off the battlefield.

Approaching the 150th Pennsylvania Infantry, Burns — according to the unit’s officers — asked if he could fight with them. Answering their inquiries about his combat experience, Burns claimed he had fought at Lundy’s Lane during the War of 1812 and showed off the ammunition for his gun. The Pennsylvanians reported that they directed him toward McPherson Woods.[v]

In or near McPherson Woods, Burns ran into officers from the 7th Wisconsin who asked him who he was. Learning his story, they gave him a better rifle and let him approach their battle line. As the story goes, Burns sniped at a Confederate officer riding toward the woods and knocked him off the horse.[vi]

For some reason, Burns shifted to the left, coming in contact with officers of the 24th Michigan. According to their records, the old man was wounded while in or near their battle line and one of their surgeons bandaged his injuries. One of the regimental chaplains later visited Burns a couple weeks after the battle.[vii]

Henry Dustman who lived not far from the Lutheran Seminary gave a version of what happened next:

A soldier came to me and said, “There is an old man laying over there on the cellar door (pointing across the road to the little brick house), wants to see you.”

“Who in the world wants to see me now, in all this fighting!” However, I lost no time and went over. There lay John Burns on the cellar door. I said to him, “Why, John, what is the matter?”

He said, “Oh, Henry, I took my gun and went out fight and got wounded,” at the same time showing me his ankle.

Doubting his story, I asked where his gun was. He said, “I took my pocket knife and buried it near that sour apple tree,” at the same time, showing me where he was wounded, “then crept from there on my hands and knees to this cellar door. Go and tell my wife to get a wagon to take me home in.”

I said, “That will be something to do.” However, I went.

But it seemed to me while walking over that quarter mile of pike there was a lull in the fighting. I told Mrs. Burns what had happened, that John was wounded and that she should get a wagon and get him home.

She did not get at all excited, but said, “Him. I told him to stay at home.” And that was all that she said or did.[viii]

John Burns did make it to safety with the help of some of his neighbors, the Sellingers, who proved to be more sympathetic or more forgiving that his wife. At some point during the Confederate occupation of the town, several officers came to visit the wounded civilian and questioned him about his role in the battle. After they left, Burns claimed that two bullets flew through the window of his house, into the room where he was, and just barely missed him. Burns firmly believed that Confederate assassins were out to get him.[ix]

The assassin conspiracy might be linked to yet another Burns-connected story. 2 Jane Powers McConnell remembered: “We lived on High Street. There was a neighbor at the other end, ill with small pox. John Burns got it into his head that she was a Rebel sympathizer, which was far from the case. John met a group of Rebel officers and soldiers on High Street, and a happy thought struck him. He’d play a joke and get even with the woman. He told them this woman had a number of Union men hidden in her house and considerable powder stored out of sight in her cellar. They lost no time reaching the house, and they flew out of it quicker than they entered when she told them she had small pox.” The poor woman ran from her home, convinced that it would be shelled because of the rumors and she dashed up the street “without a shoe on, nor any hair on her head.” Finally meeting with a sympathetic neighbor (not John Burns) she poured out her tale.[x] Was this old woman the one that Burns believed that told on him?

During and after the battle, one of Burns’s new pastimes was denouncing supposed Confederate collaborators. People he did not like, men who refused to fight with him, and even civilian women came under his attacks. Mary Virginia Wade, the young woman killed on July 3, 1863, was not exempt from John Burns’s claims of Confederate sympathies.[xi] Perhaps the old fellow just needed new personal battles and quarrels to fight. Or perhaps he realized he could have better hero story if he presented himself as the only civilian male who went out to find for the Union from a community of Rebel sympathizers? (There were a few other civilians who trailed the military and may have even fired a few shots, but Burns is the best known and most recognized.)

John Burns recovered from his wounds and added another proverbial feather to his hat in November 1863. He met President Lincoln, and according to one eyewitness, “Baltimore Street was a surging mass along the fourth of a mile that Lincoln and Burns marched arm in arm, the President and his tall silk hat towering far above the little stooped veteran beside him, and above all who were on the street. They seemed an ill-assorted pair, and they certainly could not keep step, try as they would.”[xii]

Burns seemed to enjoy his local celebrity status, but whether it made him a more pleasant neighbor remains open for debate. Probably set in his ways, the old patriot probably continued to peddle a few of his conspiracy theories, poke his nose into other people’s business, and quarrel with those around him. Some habits never die, even with heroic celebrity status. Burns died in 1872 and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery, Gettysburg, but the stories of his life and the legends that have been built live on in history books and Gettysburg lore.

Sources:

[i] Jim Slade and John Alexander, Firestorm at Gettysburg (Atglen: Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1998), 29.

[ii] Ibid., 145.

[iii] George Sheldon, When The Smoke Cleared At Gettysburg, (Cumberland House, 2003), 62.

[iv] Jim Slade and John Alexander, Firestorm at Gettysburg (Atglen: Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1998), 80

[v] Henry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The First Day (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 357-358.

[vi] Ibid, 358.

[vii] Ibid, 358.

[viii] Jim Slade and John Alexander, Firestorm at Gettysburg (Atglen: Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1998), 80-81

[ix] Gerald R. Bennett, Days of Uncertainty and Dread, (Littlestown, Bennett, 2002) 60-61.

[x] Jim Slade and John Alexander, Firestorm at Gettysburg (Atglen: Schiffer Military/Aviation History, 1998), 107.

[xi] Margaret S. Creighton, The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History: Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War’s Defining Battle (Basic Books 2008) 197-198.

[xii] Linda Giberson Black, Gettysburg Remembers President Lincoln (Gettysburg, Thomas Publications, 2005) 53.

Great post, Sarah! Folks wishing additional information may also wish to read Tim Smith’s, “John Burns: The Hero of Gettysburg,” that was printed in 2000 by Thomas Publications.

Who doesn’t have a “Get Off My Lawn” tee shirt?

Thanks for yet another great human interest story … you are amazing productive and a wonderful writer … and speaking Gettysburg townies, i eagerly await something on “the of the story” of Jenny Wade … i understand there’s some mythology there as well.

Wonderful as always, Sarah. Also, I’ve really been enjoying your Gettysburg 159 ABT videos with the great Garry Adelman! Great work (although I’d say Henry’s middle name is pronounced kid not kide)!

Great work Sarah! Sounds like this guy was a momentary hero, but a POS otherwise.