The Origin of Joshua Chamberlain’s Mustache

ECW welcomes back guest author Evan Portman

Every Civil War buff, young and old, recognizes the iconic mustache of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain. It has become almost as legendary as the man himself. Chamberlain’s key role in The Killer Angels and portrayal by Jeff Daniels in the subsequent film Gettysburg have ingrained the mustached Chamberlain in American mythology. Represented on T-Shirts, postcards, coffee mugs, and other paraphernalia, Chamberlain’s mustache has grown to be synonymous with his identity. (I even remember sporting a penciled-in mustache as part of my Chamberlain Halloween costume one year.) But how did Chamberlain’s famous ‘stache, which he sported for the rest of his life, come to be?

Born in 1828 to a pious and conservative family, Joshua Chamberlain grew up as a timid and quiet boy. By 1848, the now twenty-year-old Chamberlain conquered his childhood speech impediment to enter Bowdoin College. Though studying to become a minister, the young Chamberlain had always entertained thoughts of a military career, which his father desired him to follow. Abandoning his path to the pulpit, the mild-mannered Chamberlain accepted a professorship in 1855 at Bowdoin College teaching natural theology, logic, and freshman Greek. Several months later, Bowdoin offered him a higher salary to teach rhetoric and oratory.

By 1860, on the eve of civil war, Joshua Chamberlain settled into marriage and fatherhood, residing peacefully in Brunswick, Maine with his wife Fanny and two children. The following year, everything changed. After the first shots thundered across Charleston Harbor, Maine reacted to the national crisis like every other state by raising regiments and sending its sons off to war. Chamberlain watched as war fever gripped his students and they enlisted to join the fledgling Union army. “Nearly a hundred of those who have been my pupils, are now officers in our army,” the 33-year-old professor wrote, impatient that he was unable to join the conflict himself – or so he thought.[1]

But by 1862, as the war entered its second year, Chamberlain began to grow more restless. Those around him, including his students, noticed that the shy and stuttering professor was now bolder and more impassioned about the present conflict. One of Chamberlain’s students recalled that he underwent a “sudden transformation from a person of exceptional mildness to one of extreme military ardor.” Chamberlain wrote years later, “The flag of the nation had been insulted. The honor and authority of the Union had been assaulted in open and bitter war. The north was at last awake to the intent and magnitude of the Rebellion. The country was roused to the peril and the duty of the hour.”[2] Also “roused to the peril and the duty of the hour” was Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

Thus, in the spring of 1862, Chamberlain found himself at a crossroads in life. Bowdoin offered him a lifetime professorship of Modern Languages which included a two-year sabbatical to travel and study in Europe. Tempted by this promotion, Chamberlain also felt compelled to join the conflict about which he felt so passionately. While he accepted Bowdoin’s offer, he secretly wrote Governor Israel Washburn and offered his services to the state. Washburn appointed Chamberlain lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine, a regiment composed of surplus recruits for Maine’s quota of four more regiments in President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers.[3]

As the regiment drilled at Camp Mason in the summer of 1862, the bookish and bespectacled Chamberlain met frequently with the regiment’s commander, Colonel Adelbert Ames, who tutored the young professor in military strategy and jargon. A skilled learner, Chamberlain chose to follow Ames’s example instead of immediately accepting command of the regiment himself.[4] In September, though, the 20th Maine left Camp Mason near Portland and headed for Alexandria, eventually joining the Union Army of the Potomac in its pursuit of the Confederate army’s invasion of Maryland. Held in reserve for the Battle of Antietam, Chamberlain and the 20th Maine lightly engaged the Confederate army in the Battle of Shepherdstown, where the regiment took its first three casualties.[5] Pausing to continue its training near Shepherdstown, the 20th soon rejoined the Army of the Potomac in Virginia.

During this time, Chamberlain wrote Fanny describing his adventures. He enthusiastically recounted his day-to-day duties, including command of a picket line, witnessing a skirmish or two with Confederate cavalry, and temporarily commanding the regiment from time to time when Ames assumed command of the brigade. Chamberlain fondly recalled an incident when he led the regiment as President Lincoln reviewed the army near the battlefield of Antietam.[6] His transformation from an academic to a soldier was nearly complete, but Chamberlain still looked more the part of a bookish professor.

On November 22, 1862, Chamberlain wrote Fanny from the 20th Maine’s camp near Hartwood, Virginia. In his letter, the lieutenant colonel expressed his boredom between campaigns, relating that he, along with Colonel Ames, Major Charles Gilmore, and the regiment’s doctor and adjutant, resorted to sitting around the fire telling ghost stories and “other marvelous tales” to entertain themselves in the cold, wet, and rainy camp.[7]

Midway through the letter, Chamberlain recounted a story in which he casually described the origin of his famed mustache. Earlier in the day, he wrote, the 20th Maine’s adjutant John Marshall Brown “took the opportunity […] of cutting my beard to suit his notion of my face.” Chamberlain continued:

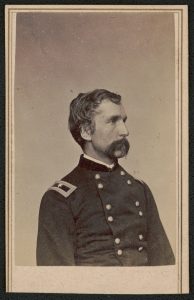

He has left me with a ferocious mustache and my bit of an imperial only. The ends of the mustache he has waxed and twisted and they reach positively the angle of my jaw […] and would almost meet under my chin. Mr. B. thinks he has me now to suit him – especially for a profile. You would not know me.

Indeed, Chamberlain was left nearly unrecognizable (a simple comparison of photographs confirms this for any skeptic), for he had abandoned his scholarly appearance for a more contemporary style. Facial hair was common among 19th Century officers or enlisted men, especially “in a much-bearded army,” as Major Abner Small of the 16th Maine coined. A mustache and “imperial” (or a small, tufted beard) were a popular combination among younger officers, following the example of Emperor Napoleon III.

However, Chamberlain’s dramatic physical transformation only followed as a manifestation of his change in mindset. In his next letter to Fanny, Chamberlain wrote that he felt “cramped at the thought of going back” to Bowdoin, having tasted a military career.[8] A confident army officer was taking the place of the bashful professor. Before long Chamberlain would be achieving fame on the slopes of Little Round Top, in the trenches of Petersburg, and the streets of Appomattox, accompanied by the iconic mustache he kept for the rest of his life.

Evan Portman is a fledgling historian and continuing education instructor with the Penn-Trafford Area Recreation Commission, giving frequent lectures on their behalf. His interest and enthusiasm for Civil War history began with a trip to Gettysburg when he was seven years old and has grown ever since. He is currently pursuing a History major and secondary education minor at Saint Vincent College and will graduate in the spring of 2022.

[1] Joshua L. Chamberlain. Joshua L. Chamberlain to Gov. Israel Washburn, July 14, 1862, Letter. From Bowdoin College , The Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Collection, https://learn.bowdoin.edu/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain/documents/1862-07-14.html (accessed July 7, 2022).

[2] Thomas Desjardin, Joshua L. Chamberlain: A Life in Letters, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2012), 165.

[3] Thomas A. Desjardin, Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine: The 20th Maine and the Gettysburg Campaign, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 3.

[4] Joshua L. Chamberlain. Joshua L. Chamberlain to Gov. Israel Washburn, July 14, 1862, Letter. From Bowdoin College , The Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Collection, https://learn.bowdoin.edu/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain/documents/1862-07-14.html (accessed July 7, 2022).

[5] Desjardin, Stand Firm Ye Boys from Maine, 3.

[6] Thomas Desjardin, Joshua L. Chamberlain: A Life in Letters, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2012), 171.

[7] Desjardin, Joshua L. Chamberlain: A Life in Letters, 173.

[8] Desjardin, Joshua L. Chamberlain: A Life in Letters, 177.

Thank you, Evan, for this post explaining Chamberlain’s “trademark” mustache. His two statues here in Maine (Brunswick and Brewer) each feature the mustache.

You’re welcome! I thought it was interesting how he left an account of this.

Evan, thanks for a great essay … Chamberlin made the mustache “cool” long before Sam Elliot.