Julius Peter Garesché’s Anonymous, And Anomalous, Fame As An Author

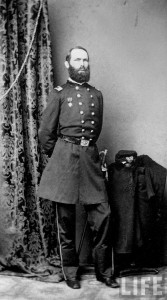

Julius Peter Garesché was a Civil War officer who literally lost his head in the Battle of Stones River, fulfilling a prophecy that he would die in his first battle. A friend of General William Rosecrans since West Point days, Garesché had helped persuade Rosecrans to join the Catholic Church. As commander of the Army of the Cumberland, Rosecrans persuaded Washington to send Garesché from a staff position in the capital to serve in Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland.

Garesché almost certainly wrote an 1859 article which is somewhat famous today, for non-Civil-War-related reasons. Perhaps I should say infamous, because the article, when cited today, is generally cited in mockery.

The article was for the Catholic periodical Brownson’s Quarterly Review, edited by the intellectually restless convert-intellectual Orestes Brownson. The article, written over the initials “J. A. G.,” attributed dire dangers posed to a regime of easy divorce.[i]

The author said that in a regime which allowed divorce for “incompatibility of temper,” as some would-be reformers were urging, married people might, even during their marriages, be open to trading in their in their old marriage for a new one. “[A] wild flood of passion” could overwhelm all barriers and make marriage “a mere empty name.”[ii]

“[S]avage broils, and ceaseless discord” would flow from the ensuing free-for all.[iii] Children would learn from the bad example of their parents. Mothers, without fathers, would have trouble “governing unruly boyhood,” and fathers, without mothers, would have trouble raising girls properly. Once allowed, the bad example of divorce would spread the blight from generation to generation.[iv]

Weakening marriage would have a tendency “to break up society” and undermine allegiance to the government. The author cited the advantages of monogamy among other animals, and invoked Roman history to illustrate divorce’s pernicious effects on a human community. “[D]ivorce laws but pave the way for polygamy and the grossest sensuality.”[v]

Proceeding to Scripture, the author countered Protestant arguments allowing divorce at least in the case of adultery with what he deemed unambiguous Scriptural proofs against divorce. The Catholic Church provided the needed supernatural supports for marriage by making marriage itself a sacrament and giving married people access to Confession and the Eucharist.[vi]

“[T]he sad first-fruits” of divorce were already showing in the deterioration of private and public virtue, including in the rise of Mormonism. The human race was physically deteriorating, respect for chastity was diminishing, and even married people were using contraception and abortion. The peroration was dire: “The family, in its old sense, is disappearing from our land, and not only our free institutions are threatened but the very existence of our society itself is endangered.” The way out was educating public opinion, “consecrating anew Christian marriage,” and repealing laws permitting divorce.[vii]

This particular article, specifically the “disappearing from our land” sentence at the end, has had quite an afterlife long after it was first published. Starting no later than the 1970s, and extending to this day, article after article, book after book, in both academic and popular sources, have mockingly cited this passage as evidence that there have always been gloom-and-doom prophecies about the fate of the American family. (We can find examples of these citations by searching Google Books and Google’s main search engine for the phrase “the family in its old sense is disappearing from our land”).

Curiously, not only are these critics unaware of the author’s identity, they consistently misattribute the article’s remarks to the Boston Quarterly Review, a former publication by Brownson which had been defunct for years by 1859.

The critics didn’t seem to know that Julius Garesché’s son Louis, in a privately-published memoir of his father, credited Julius with authorship of the marriage article. Louis said that the article was printed over the initials “J. P. G.,” not the actual “J. A. G.”[viii] This may cast some doubt on the attribution, but the chance is that Louis was aware of the authorship.

Brownson’s son Henry, in a biography of Orestes (loyal sons seemed to be writing biographies of their fathers back then), wrote that Orestes was “a very strong friend” of each of the three Garesché brothers – Alexander, Frederick and Julius.[ix] So if someone in the Garesché family claimed to know that Julius wrote an article in Brownson’s magazine, the attribution was probably correct.

Julius Peter Garesche (1821-1862) was born in Cuba to a Protestant Huguenot father and a Catholic mother. Though the marriage contract specified that the sons of the marriage must be raised Protestant, Julius’ father allowed him and brothers to become Catholic (the father becoming Catholic himself on his deathbed). Julius graduated from West Point in 1841. After graduation, he discussed religion with a friend he had met at West Point, William Rosecrans, who later joined the Catholic Church.[x]

Julius was assigned to various staff posts around the country, working in the Adjutant General’s Department. In Texas he faced accusations of misconduct from an accuser who was himself reprimanded for wrongly prosecuting Garesché. Despite hassles like this, Garesché was a conscientious officer who was also dedicated to religious good works. Pius IX made him a Knight of St. Sylvester.[xi]

One might ask about Julius’ own marriage. Louis is the source of our information on this, and Louis gives us translations of family letters from French. The strains of Julius’ military career, including the low pay, was compounded by Julius’ charitable giving which Mariquitta considered excessive.[xii] Still, it appears to have been a loving marriage.

As the Civil War began, Julius became a Major in the Adjutant General’s Corps, serving in Washington. Even before the war, Garesché had experienced premonitions of violent death, and now he received a prophecy that he would die in his first battle. Despite this looming occupational hazard, Garesché persuaded his superiors to release him from his Washington desk job to serve on his friend Rosecrans’ staff, as the general had requested.[xiii]

In his 1859 article, Garesché hadn’t mentioned the greatest threat to American marriage, namely, the institution of slavery – with husbands and wives, parents and children, being sold away from each other, and slave marriages being prohibited. But Julius Garesché had reasons to hesitate before attacking slavery. His family (on both sides) had been driven out of Haiti during the slave rebellion there, losing their property and aware of the many whites who were massacred. This was not something the family forgot readily, as indicated by the fact that as late as 1888, Julius’ son Louis was trying to get compensation for the Gareschés’ Haitian losses. The lesson of the Haitian rebellion, as assimilated by Julius, was that freeing slaves was associated with bloody revolutionary violence.[xiv]

Believing as he did, Garesché was appalled by President Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. If Lincoln actually carried out his promise to free large numbers of slaves, Garesché was determined to resign from the Army. Garesché retained some hope that Lincoln, chastised by Republican losses in the 1862 elections, might reconsider giving a final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but if Lincoln carried out that intention, Julius intended to quit the war. He would not fight for emancipation (putting him at odds with his commander William Rosecrans, who had become an emancipationist).[xv]

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Stones River, Garesché took communion at dawn along with his commander, and, “bright and animated” (in Rosecrans’ later recollection), he and other officers rode across the battlefield with the general. While General Rosecrans and his staff were approaching the center of the battlefield, a cannonball took off Garesché’s head. When the battle had lulled enough by the end of the day, Garesché received a hasty temporary burial. When January 1 came, Lincoln did indeed issue his Final Emancipation Proclamation as promised, but by then Julius Garesché was freshly dead. He had been faithful to the Union to the end, and he received a hero’s honors in in the North.[xvi]

Whether Garesché’s dire warnings about marriage back in 1859 were correct, they at least had the effect of potentially making him more famous for one article than for his entire Civil War career – if he had been known as the author, that is.

Sources:

[i] “J. A. G.,” “Divorce and Our Divorce Laws,” Brownson’s Quarterly Review, October 1859, 473-92.

[ii] Ibid., 473-75.

[iii] Ibid., 475 ff.

[iv] Ibid, 475-78.

[v] Ibid., 479-85.

[vi] Ibid., 485-91.

[vii] Ibid., 491-93.

[viii] Louis Garesché, Biography of Lieut. Col. Julius P. Garesché, Assistant Adjutant General, U. S. Army (Philadelphia: printed for private circulation by J. B. Lippincott and Company, 1887), 326.

[ix] Henry F. Brownson, Orestes A. Brownson’s Middle Life: From 1845 to 1855 (Detroit: H. F. Brownson, 1899), 341-42, 343-45.

[x] Louis Garesché, 17, 23, 38, 49-53, 393.

[xi] Ibid., 53, 59, 65-75, 85-135, 138-39.

[xii] Ibid., 123-24

[xiii] Ibid., 63-65, 352-55, 357-61, 389, 393-97.

[xiv] Louis Garesché to the French minister to the United States, August 28, 1889, Louis Garesché papers, Rubenstein Library, Duke University, Durham, NC, cited in Max Longley, For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015), 182

[xv] Longley, 182.

[xvi] Louis Garesché, 451-70 Longley, 194; Rosecrans to Dallas, Julius Garesché Papers, Special Collections, Georgetown University, cited In Longley, 193, 195.

Author, good article, but your barely veiled, light-hearted quips regarding how this man was killed were irritating.

Given the current dysfunctional nature of the modern self indulgent and narcissistic American “family”, I would tend to put a little more credence in Mr G’s prescience.

Sounds like he and Mr. Comstock might have gotten along if he lived to see the last couple of decades of the 19th century… I don’t necessarily consider that a good thing, but it shows the roots of reform reach back a little farther than the traditionally accepted years of the Progressive Era.

I, too, picked up the mirth imparted by Mr. Longley about this officer’s death. Readers are encouraged to dismiss any empathy for the fallen soldier. The s.o.b. deserved his fate, daring to express, as he did, an opinion on the implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation (common at the time), but so out of touch with today’s more enlightened thinkers.

i was surprised to read about Garesche’s public opposition to the Emancipation Proclaimation — what is your source? Your endnote only says “Longley, 182”.

For a source which isn’t my own book, see another volume cited in this article: Louis Garesché, Biography of Lieut. Col. Julius P. Garesché, Assistant Adjutant General, U. S. Army (Philadelphia: printed for private circulation by J. B. Lippincott and Company, 1887), 351-52.