The White Belgian Astronomer Who Became a Black American Civil Rights Leader

Historians of the American Civil War and Reconstruction enjoy a seemingly limitless reservoir of colorful characters and their compelling stories. Biographies of senior military leaders, government officials, and notable activists abound, alongside hundreds of B-List personalities, whose connection to key people and events thrust them into the spotlight momentarily. But brief accounts of many thousands of obscure Americans offer an intimate window into this transformational period in our history.

I became acquainted with Jean-Charles Houzeau as one of three conspirators in a secret plot that effected the escape of outspoken Unionist Charles Anderson from incarceration in a Confederate military camp east of San Antonio, Texas in 1861. It was a dramatic incident that the New York Times called, “among the most moving and romantic episodes of the war.” Houzeau appears for eight pages in my Anderson biography, then vanishes, but his life story is fascinating.[i]

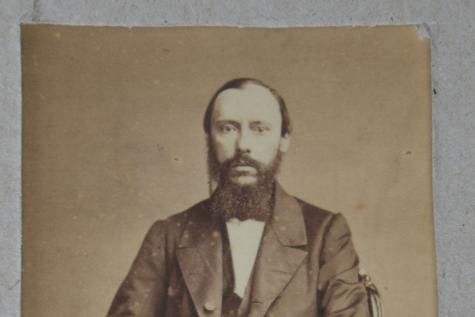

Houzeau was born in 1820 at the sumptuous Ermitage de St. Barthélemy near Mons in the Waloon Region of present-day Belgium. His parents were wealthy aristocrats and political radicals who espoused the values of the French Revolution. During winters in Paris, he lived at the Sorbonne with this uncle, but his independent temperament and aversion to discipline kept Houzeau from finishing university. He began publishing scientific essays on industrialization at the age of nineteen and became obsessed with astronomy. His groundbreaking research on double stars won the attention of leading astronomers, resulting in his appointment as assistant professor at the Royal Observatory in Brussels in 1846. When Europe erupted in revolution in 1848, Houzeau discovered that, at least for the moment, his political principles trumped his career aspirations.

The young scientist wrote articles in liberal newspapers calling for social and political reform and became an officer in the Belgian secret society Phalange. He chaired a democratic rally in December 1848, barely escaping a violent mob of royalists, and was dismissed from the faculty of the Royal Observatory the following April. He spent the next several years publishing a wide range of scientific and historical works, leading to his election to the Belgian Royal Academy in 1856. But like many European radical intellectuals, Houzeau’s curiosity led him to America, where he landed in New Orleans on October 28, 1857. By the spring of 1858, he had moved to Texas.

Houzeau reveled in his “vagabond existence” on the plains of the Texas frontier, surveying land, studying natural life, and making celestial observations. But his enthusiasm for American democracy and natural resources was diminished by has hatred of slavery. When Texas seceded in 1861, Houzeau vowed to cut off his right hand rather than submit to Confederate authority. He began covertly aiding Union families and runaway slaves until he became a target, He escaped to Mexico in February 1862 and was sheltered by a free Black family in Matamoros. Houzeau used his membership in the Belgian Royal Academy to petition U.S. authorities for transfer back to occupied New Orleans in January 1863. In November 1864, he accepted managing editorship of the New Orleans Tribune, America’s first Black daily newspaper.

Black Creoles began advocating for racial justice soon after Union forces captured the city in April 1862. Buoyed by the presence of 10,000 free people of color and 15,000 enslaved residents, they founded the twice-weekly, French language newspaper L’Union to help make the principles of the Declaration of Independence a reality. Houzeau wrote frequently for the fledgling sheet. When it folded and was replaced by the Tribune, its proprietors promised readers that the paper would be “edited by men of color” and not “controlled by any white man.” They knew full well that Houzeau, despite his dark complexion, had no African blood, but the new managing editor easily passed as a man of color in a city where racial mixing had been common for more than one hundred years. White authorities and even future historians assumed that Houzeau was Black.

Houzeau’s editorials advocated for integrated schools and public places, universal manhood suffrage, and the right for people of color to serve on juries, but his most passionate pleas came when Louisiana leaders hinted that white plantation owners would be allowed to retain their lands. “Can a planter be expected to treat the laborers under his control in any other way to-day than he has treated them for the last twenty years?” he asked. Houzeau’s remedy revealed his affinity for philosophers like French utopian socialist Charles Fourier. Land should be placed into the hands of laborers, he argued, by purchasing shares in self-help banks, who would then rent them to worker associations. White elites bristled at the thought.

Houzeau’s influence grew rapidly and his thriving paper circulated among key anti-slavery leaders like Senators Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson. Landmark legislation like the Civil Rights and Southern Homestead Acts of 1866 contrasted with Louisiana’s new government of 1865, composed almost entirely of Democrats and former Confederates. The state’s Freedman’s Bureau was ineffective, understaffed, and under constant threat of violence from recalcitrant whites. Tensions finally came to a head at the state constitutional convention on July 30, 1866.

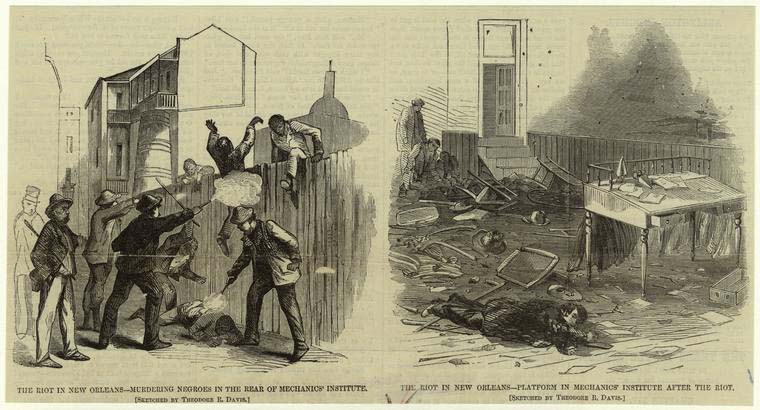

In what became known as the New Orleans Massacre of 1866, a mob of white, mostly ex-Confederate soldiers attacked a group of Blacks assembled peacefully on the street outside the Mechanics Institute. Republican leaders had called the convention in response to laws passed by the Louisiana legislature that denied Black suffrage. Official reports cited 34 dead and 119 wounded among New Orleans Blacks, but unofficial casualty estimates ran much higher in the bloodiest riot of the Reconstruction Era.

Houzeau wrote his brother in Belgium, claiming that “several hundred” people died in the melee. He had just left his seat in the convention hall when he heard the sound of gunfire. He watched the planned and organized attack from the window as unarmed civilians held off the assault for half an hour, retreating into the building. At a signal from the mayor, a bell in city hall sounded, marshalling about five hundred armed policemen who aided the mob in breaking doors and forcing their way into the building. Houzeau and others escaped down a service staircase into the yard where dead victims laid beside rock-throwing defenders, scrambled over a wall, and took refuge in a furniture shop.

Houzeau described the scene he witnessed through a keyhole. “The people in the streets were being beaten and shot at point-blank range; they were chased into houses to the accompaniment of wild shouts. The heads of the wounded lying on the ground were crushed. The houses next to the hall where the convention was held were attacked and captured; all their inhabitants without distinction were killed. Policemen in a frenzy stopped buses and killed any blacks found on them, including children.” When U.S troops finally arrived at 3:30 p.m. from their quarters outside the city, Houzeau lamented, “no one was left to be killed.”

For six days following the massacre, Houzeau worked as much as twenty hours a day, writing twenty-eight columns of editorials in French and English and interviewing two hundred witnesses to prepare testimony for the War Office. He accused state government officials of acting as accomplices to the “cold-blooded horrors.” “These are proslavery advocates of the worst kind,” he explained. “In Europe, it must be difficult to understand why such highly placed, rich men, belonging to the upper stratum of society, support something so despicable. It is the effect of a long possession of man by man. The moral sense is destroyed, in every respect. These men do not see themselves as committing a crime. For them this is a little preventative antidote against the reformers and the anarchists.”

When military Reconstruction secured the franchise for Blacks in 1867 and a liberal state constitution seemed certain of adoption in 1868, Houzeau had reason to celebrate. However, the hard-won victory only renewed rivalries between many mixed-race blacks who considered themselves superior to freedmen. Houzeau resigned in disgust on January 18, 1868, and sailed for Jamaica in May. In 1870, he published My Passage at the New Orleans Tribune, a memoir of his three-year stint at the Tribune. He returned to Europe in 1876, accepting the directorship of the Belgian Royal Observatory, which had dismissed him for political activism twenty-seven years earlier. When he died in 1888, tributes from all over Europe lauded his accomplishments, but the New Orleans press was silent.

Houzeau’s contributions to the Black community of New Orleans were properly recognized in 1984, when David C. Rankin of the University of California, Irvine published his memoir in English through Louisiana State University Press. Houzeau himself had a simple take on his unusual legacy. “For myself, who knew how to make myself a proletarian in Europe, it has not been difficult to make myself black in the United States. I think and I feel that which a freedman must think and feel. I do not consider things from the view of a protector, but as they have told me a hundred times, I really am one of them.”[ii]

David T. Dixon is the author of The Lost Gettysburg Address: Charles Anderson’s Civil War Odyssey and Radical Warrior: August Willich’s Journey from German Revolutionary to Union General.

[i] David T. Dixon, The Lost Gettysburg Address: Charles Anderson’s Civil War Odyssey (Santa Barbara: B-List History, 2015), 88—95.

[ii] Jean-Charles Houzeau, David C. Rankin, ed., Gerard F. Denault, trans., My Passage at the New Orleans Tribune (Baton Rouge: Louisiana Univ. Press, 1984).

What a great story, David!!

a really great true story. you can’t make this stuff up!