“We Scarcely Know How to Express Our Indignation:” Kentuckians Face 1863 and the Emancipation Proclamation

By the time 1862 turned into 1863, most of the fighting involving the belligerent armies was finished in Kentucky. Although numerous cavalry raids and constant guerilla engagements continued to trouble the loyal slaveholding state, the war’s social and political issues began to claim a lion’s share of the citizens’ attention as 1863 loomed.

Of particular concern was President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Released in September of 1862, and set to take effect on January 1, 1863, it stated that after that date, all enslaved people residing in the states in rebellion would be free. Excluded in the measure were certain areas of seceded states under occupation by United States military forces, as well as the Border States of Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and Kentucky, all whom remained in the Union.

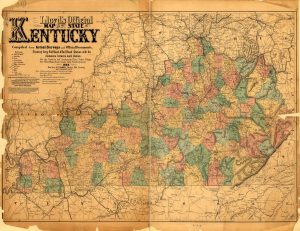

The exemption of Kentucky provided little comfort to the state’s slaveholders and pro-slavery citizens. The Bluegrass State had a heavy investment in enslaved humans. Figures from the 1860 census show that Kentucky ranked ninth out of the 15 slaveholding states in enslaved population. However, only Virginia and Georgia surpassed Kentucky in numbers of enslavers. Kentucky’s geographic location virtually ensured that the state would feel the effects of the Emancipation Proclamation. And they did. Kentucky’s long Ohio River border with the free states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois meant it would experience heavy traffic from liberty seeking Black people. And it did.

During the fall of 1862, as Union and Confederate armies moved about the state, numerous enslaved people used the confusion as a distraction and an opportunity to attempt to gain their freedom. White citizens were alarmed that their race-based system of social order—in place since attaining statehood in 1792—seemed to be rapidly breaking down.

Most White Kentuckians despised native son, Abraham Lincoln in 1863. A short article ran in the Louisville Democrat on January 3, 1863, that the Frankfort Tri-Weekly Commonwealth then re-ran two days later. The editor for the Frankfort paper explained that, “We have expressed our condemnation of this highhanded assumption of power by President Lincoln, in almost every issue of our paper since the appearance of his Proclamation on the 22d of September last [1862].” Apparently, unable to word it any better, and because the article “so fully expresses our own opinions upon this subject, that we adopt them as our own,” the editor of the Frankfort paper copied the article verbatim. It reads:

The President’s proclamation has come to hand at last. We scarcely know how to express our indignation at this flagrant outrage of all Constitutional law, all human justice, all Christian feeling. Our very soul revolts at contemplating an atrocity so heinous, and the feeling is intensified at the indelible disgrace which it fixes upon our country. To think that we, who have been the foremost in the grand march of civilization, should be so disgraced by an imbecile President as to be made to appear before the world as the encourager of insurrection, lust, arson, and murder! The people have condemned this in advance, and the President has raised a storm that will overwhelm him. It is not in the rebellious States he has to fear most, but the true, loyal States will not suffer their fame to be stained by him. It is not enough that Kentucky is exempt from its force; not enough that it is ineffectual even in the States it has reference to. The people cannot, in any State, bear to be so slandered by one who usurps authority. [i]

The state’s constituency forwarded their disdain for President Lincoln and his edict to the General Assembly, who within two months, passed a set of laws in attempt to combat the growing number of freedom seeking Black men, women, and children; some of whom were Kentuckians, and others who were just traveling through the commonwealth.

The six sections of the law read:

An Act to prevent certain negroes and mulattoes from migrating to or remaining in this State.

Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky:

-

- That it shall not be lawful for any negro or mulatto claiming or pretending to be free, under or by virtue of the Proclamation of the President of the United States, dated 1st January, 1863, declaring free slaves in certain States or parts of States, or any similar proclamation, by order of the Government of the United States, or any officer of agent thereof, to migrate to or remain in this State.

- Any negro or mulatto who shall violate the provisions of this act shall be arrested, dealt with, and disposed of as runaways, and the proceedings shall conform to the laws in existence, at the time they are had in relation to runaway slaves.

- The purchaser of any such negro or mulatto sold under and by virtue of such proceedings shall, by virtue of such purchase, acquire and have the same right to, the same property in, and control over such negro or mulatto as masters have over their slaves under existing laws, subject to the provisions in relation to slaves sold as runaways, and shall in all respects be by the law in relation to master and slave.

- The purchase money for such negro or mulatto shall not be paid into the public treasury until the right of redemption shall have expired or been finally determined by adjudication, in case the same be put in litigation, as provided in relation to slaves sold as runaways, and the court shall have power to loan the same, in the meantime taking bond and security for the same.

- It shall be the duty of all peace officers to see that the provisions of this act are enforced.

- This act will take effect from its passage.

Approved March 2, 1863.[ii]

In addition, to help reduce the number of captured enslaved people overcrowding Kentucky’s jails, the General Assembly passed another law the same day that reduced the mandatory advertising time. With the new law, jailers now only had to advertise their captured person for a month. If their enslaver did not claim them within 30 days, the enslaved person could be offered for sale to cover the costs of their lodging, feeding, and advertising.

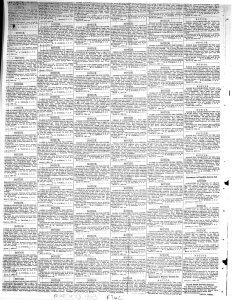

The new laws had little effect on curbing runaways. Providing excellent evidence of this fact is a page of the March 23, 1863, edition of the Tri-Weekly Commonwealth. Over 75 notices of captured and jailed enslaved people fill the page. Information gained from the enslaved individuals about their backgrounds showed they came from Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Missouri, Mississippi, Virginia, and Louisiana. At least two individuals claimed to be free [iii].

A survey of Kentucky newspaper advertisements found that jailers incarcerated 234 enslaved individuals as captures in 1863. That number was down from 242 people in 1862. But, in 1864, as the United States army finally started enlisting Black men in Kentucky that spring, the number dropped drastically to 82. In 1865, although slavery was still legal until December of that year, only 11 individuals appeared in capture advertisements.[iv]

Despite its supposed exemption from the Emancipation Proclamation, Kentucky’s enslavers and pro-slavery citizens could see the threat the document posed to slavery within the state and the changes it would mean to their lives. Fighting back with new strengthened state laws in 1863 ultimately did little to stop the enslaved, their pursuit of freedom, and eventually, the end of slavery.

Sources:

[i] Frankfort Tri-Weekly Commonwealth, 5 January 1863.

[ii] Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Frankfort, KY: John B. Major Public Printer, 1863, 366.

[iii] Frankfort Tri-Weekly Commonwealth, 23 March 1863.

[iv] Timothy Ross Talbott, “Telling Testimony: Slavery Advertisements in Kentucky’s Civil War Newspapers,” Ohio Valley History, vol. 16, no. 3 (Fall 2016), 36.

Tired of the modern necessity of using weaponized language like “enslavers”, as if Sauron’s orcs had occupied the Bluegrass.

Although forms of “enslaved” are terms that are being used more often in scholarship than they once were, it is not as if those specific words were were not being used by people of that era too to describe the “peculiar institution.” The words enslaved and enslavement appear regularly in Frederick Douglass’ autobiographies and his papers, as it also does in those of William Wells Brown, William Still, William Lloyd Garrison, and others who were formerly enslaved or fought for emancipation.

My ECW colleague, Jon Tracey, explored this topic of language and terms very well in a post on June 21, 2021: https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/06/02/a-reflection-on-historians-and-word-choice/

And, too the term does signal virtue very clearly.

Tom

Every single day people who owned and enslaved others made the conscious decision to continue enslaving them. So yes, they were ‘enslavers.’ And in fact, they’re worse than Sauron’s orcs, cause Sauron’s orcs weren’t real.

No, not exactly. “Enslave” means to reduce to or or as if to slavery. Merriam-Webster, online at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/enslave. You cannot reduce to slavery someone who is already in slavery. I think you actually mean manumit. These slave owners were non-manumiters. But, “non-manumiter” lacks the accusatory connotation and the sense of the orcs of Sauron.

Tom

The hysteria about “arson and murder” is hysterical. Enslavers try to make their own meal ticket somehow the concern of every white person.

Interesting article but one point unmentioned: When did the slaves in Kentucky and the other “exempted” States finally get emancipated? Juneteenth?

Maryland passed a state law in November 1864 that abolished slavery. Missouri did the same in January 1865. As mentioned in the second to last paragraph, slavery was not officially abolished in Kentucky (and Delaware) until December 1865, when the appropriate number of states ratified the 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

The last slavery advertisement I was able to locate in a Kentucky newspaper during my survey was placed on December 1, 1865, in the Paris, Kentucky “Western Citizen.” It was probably placed to spite the approaching 13th Amendment since it says “to the lowest bidder,” and reads: “NEGRO FOR SALE WILL be sold on next County Court day, (December 4th) to the lowest bidder, an Idiot boy, John, on the public square in Paris. Levi Sudduth

Executor of Rachel Grimes”

And slavery wasn’t abolished in Indian Territory until the USG negotiated new treaties with the four tribes in 1866.

Really interesting! Dispels the common myth that the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t really affect the Border States.

Thanks for the post.

The proclamation led to a wave of desertions in Kentucky regiments in particular. After that recruitment among white Kentuckians fell off significantly too. If I recall 71% of all white males of military age avoided service although Rebel raiders found many willing to join. I had an ancestor who surrendered at Fort Donelson, deserted after his exchange, but joined Forrest in 1864 when he rode through, fighting all the way to Selma.

The the state went hard for McClellan. Boyle’s mismanagement also played a role as he alienated nearly everyone in Kentucky.

Liddell in his memoir regrets that the Confederates treated Kentuckians with a light hand in 1862, as no more than 1,000 joined the ranks (my numbers here are not precise). He concluded “her lame halting between parsimony, love of ease, and her duty to her Southern sister states, did not justify this kind consideration at Bragg’s hands. She should have shaed the fate of the balance….Kentucky, of all Southern states, had less to complain of and more to be ashamed of. May she enjoy the blessings she sought. Kentucky showed herself indifferent to this satin in her history by losing her states rights, which her greatest men so carefully guarded in the Kentucky resolutions of 1798.” Liddell (as he often does) gets to the heart of Kentucky dropping out of the war. They fought to preserve the union and thought they could have an easy time of it. When the goal of reunion was supplemented (but never supplanted) by emancipation they could not take it. Every Confederate who said emancipation would inevitably be a major goal was proven right. Kentuckians might have felt fooled or that they fooled themselves to think otherwise, but either way most white Kentuckians were angry. But after Stones River there was no reasonable hope Kentucky would again see the Army of Tennessee marching through.

I sometimes think if Hood had made it to Kentucky the whole state might have seceded. Maybe that is one reason Grant was so nervous about Nashville?