“Paddy’s Lament” & the Irish Brigade in the Civil War (Part II)

In my previous post on the Irish ballad “Paddy’s Lament,” I shared some history of the song, discussed the events in Ireland that led so many to emigrate to America, and posed a question as to how accurate this song is in its portrayal of the Irish immigrant experience in the Civil War. Today’s post will take a look at that question.

Thousands of Irish and Irish-American New Yorkers enlisted in the Union Army when the war broke out in 1861. The majority joined three all-Irish volunteer infantries that formed the core of what would become the Irish Brigade: the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York Infantry Regiments. They were later joined by the 116th Pennsylvania and the Irish-dominated 28th Massachusetts. Most were recent immigrants; many, not yet citizens. Some, as described in “Paddy’s Lament,” were fresh off the boat: “According to one account, some of the 88th’s recruits enlisted shortly after they had exited the immigrant landing point at Castle Garden, and spoke no English, only the Irish Gaelic of the landless Catholic tenant farmer.” [1]

Between 1861 and 1865, approximately 200,000 Irishmen fought in the Civil War: 180,000 in the Union army and 20,000 in the Confederate army. An estimated 30,000 Irishmen died in the conflict. Those who fought under the “General Meagher” referenced in “Paddy’s Lament” primarily did so as part of the Irish Brigade. While they represented only a fraction of the many thousands of Irish men and women who served, in the first two years of the war, the Irish Brigade had the highest casualty rate of any comparable unit in the Army of the Potomac. In its four year history, during which 7,715 served in its ranks, “the brigade lost over 4,000 men, more than were ever in it at any one time, killed and wounded. The Irish Brigade’s loss of 961 soldiers killed or mortally wounded in action was exceeded by only two other brigades in the Union army.” [2]

It was Thomas Francis Meagher (pronounced “Mar”), promoted to Brigadier General in February 1862, who helped to rally Irish support. Born in Ireland to a wealthy merchant family and educated in England, Meagher was convicted of treason in 1848 after helping to lead a failed rebellion against British rule and sent to a penal colony in Tasmania, Australia. Four years later, he escaped to New York. Seeing how the Irish were treated and the slums in which they lived, Meagher began to speak out against anti-Irish discrimination and for Irish independence, then later encouraged Irish support for the Union war effort.

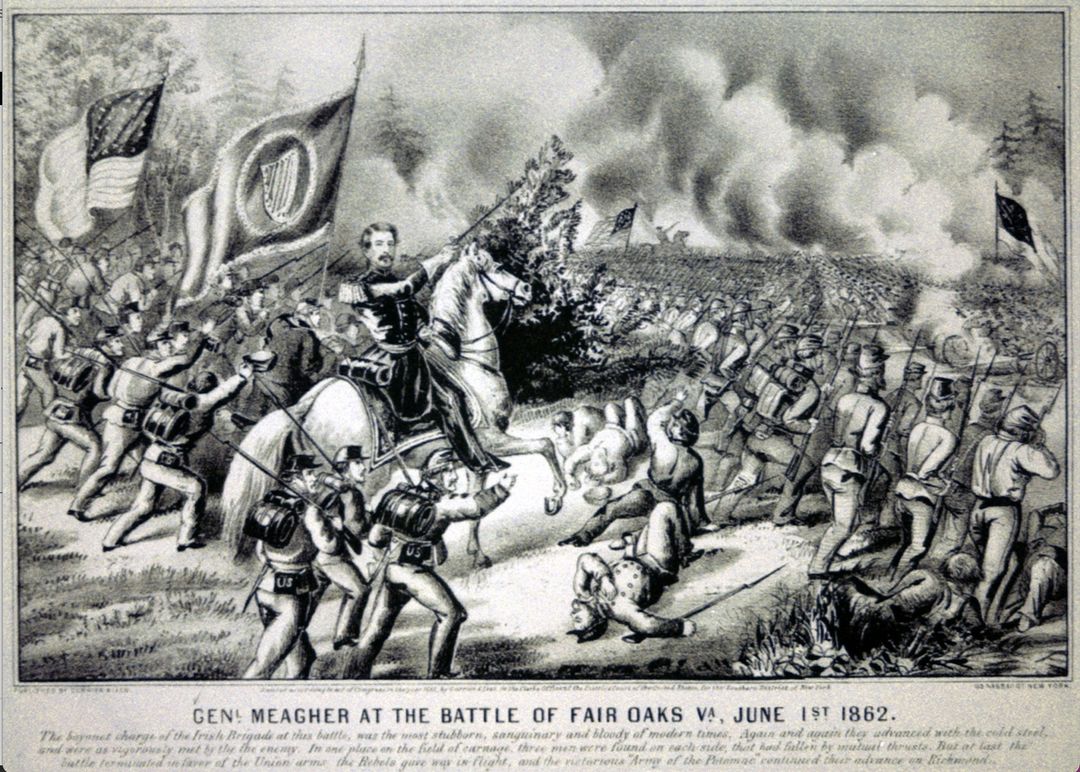

leader of the Irish Brigade [5]

Hoping that “Irish-American troops, seasoned by war, would return to Ireland and liberate their homeland from British rule,” Meagher led the Irish Brigade in many of the fiercest battles of the Civil War – including Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. [7] Often tasked with leading the charge, the brigade suffered disproportionate numbers of casualties, yet “were seen as heroes, distinguishing themselves as fierce fighters. After the Battle [of Fair Oaks], a drawing was made of him on his horse leading the Irish Brigade into battle which boosted his popularity in the Union and the Irish American community.” [8]

Despite this, the brigade’s actions at Fredericksburg impressed many – including Confederate General Robert E. Lee. “Speaking about the battle later, General Lee recalled that one of his most vivid impressions was the part played by Thomas Meagher’s Irish Brigade in the Union Army’s assaults on the Confederate lines. ‘Never were men so brave,’ he said. ‘They enobled their race by their splendid gallantry on that desperate occasion. Though totally routed, they reaped harvests of glory. Their brilliant, though hopeless assaults on our lines, excited the hearty applause of our officers and soldiers.’” [11]

Frustrated at the Union’s refusal to raise more soldiers for the brigade after its many casualties, Meagher resigned as commander in May 1863. It was Colonel Dennis O’Kane who led the Irish Pennsylvania “Fighting 69th” into battle at Gettysburg, where they “put up a magnificent fight that saved the Angle and killed any chance that Pickett’s charge could succeed,” according to Niall O’Dowd, author of Lincoln and The Irish: The Untold Story of how the Irish Helped Save the Union. “The 69th was the only regiment not to withdraw from defending the stone wall in front of the copse of trees during Pickett’s Charge. Over the two days they fought at Gettysburg, they lost 143 men out of 258 who marched onto the battlefield on the second day,” but their extraordinary courage helped to save the Republic “from dissolution at Gettysburg.” [12]

The National Conscription Act of March 1863 exacerbated the situation, as it made unmarried men between the ages of 21 and 45 subject to a draft lottery unless they could hire a replacement or pay a $300 fee. This angered the working class Irish who felt they were “being forced to fight in a rich man’s war” that was “not about preserving the Union any longer but about ending slavery—a cause that most Irish people in the U.S. emphatically did not support” because they feared the job competition that freed slaves would present. [15 ] All of this contributed to the Draft Riots that wracked New York for three days in July 1863, resulting in at least 120 people being killed (read more in this previous ECW post: “Dreadful Scenes Enacted In The City”: The New York Draft Riots”).

Irish enlistments slowed significantly after this, and those who did enlist were often motivated by financial gain. Since the Conscription Act allowed draftees to hire substitutes, “prospective substitutes were often offered hundreds of dollars to join the Union Army. Private substitute brokers sprung up in major Northern cities, facilitating such recruitment and raking in profit on commissions. In addition to the money to be made by signing up as a substitute, bounties, a form of signing bonus, were also offered to further encourage new recruits. These could be as high as $1,500.” [16]

So, where did all this leave our ballad’s singer, “Paddy”? Certainly disenchanted with the America he had dreamed would allow him to feed his hunger, end his poverty, make his fortune, and find his happiness. Instead, he found himself without one of his limbs, longing for “dear old Éirinn” or Dublin, depending on the version, and thinking he would rather have to survive on “Indian buck” than experience more war, cannons, and empty promises.

Approximately 60,000 amputations were performed during the Civil War – making up three out of four surgeries – so “Paddy” would certainly not be alone in having to adjust to life with a missing limb. Many soldiers after being subjected to an amputation “struggled with depression, shamefulness, and finding a meaningful role in society again once they returned home. This created the mounting need for pensions and/or prosthetics for wounded veterans.” [17]

A federal pension system for wounded veterans was created in 1862, but actually getting a pension was not an easy process. The United States Pension Office defined disability as “the inability to perform manual labor meaning that in order to get what many soldiers believed was a fair payment, they had to swear that they could no longer work at all. For many veterans, this was a huge step to take because it took away their manliness because they had to rely on the government for money to live and support their families.” [18]

In the ballad’s final stanza, a legless and pensionless Paddy sits cursing America and longing to be back in Ireland, where he would consider himself lucky to eat “Indian buck.” This is likely a reference to Indian corn, a type of famine relief food shipped to Ireland from America. The corn “often caused more trouble than it seemed to be worth [because] people didn’t know how it was to be cooked and received no instructions with it. It was often served undercooked, which wreaked havoc on decimated human digestive systems already in severe crisis from malnourishment, disease, exposure, etc. …. [Apparently] the singer thought it might have been a better plight to have stayed on in Ireland, even if it meant having to eat Indian corn to survive, than having been forced to ‘serve’ in the American Civil War at gunpoint, just off the boat.” [19]

“Paddy’s Lament” certainly captures the thoughts and experiences of some Irish immigrants who became Civil War soldiers. However, it does not likely speak for the majority. “Very few men left Ireland for America during the Civil War without a very good idea of what was occurring there,” according to a post on the Irish American Civil War website, “and while some were coerced and duped into service, it was far more common for them to arrive with the specific intention of enlisting – keen to reap the benefits of the once-in-a-lifetime sums on offer. While Paddy’s Lament victimizes Paddy as a largely helpless individual swept along by circumstance, this majority experience was one where men exercised their own agency, making a conscious choice both to leave Ireland and to enlist.” [20]

Endnotes

-

- Bilby, Joseph G. Irish Brigade In The Civil War: The 69th New York And Other Irish Regiments Of The Army Of The Potomac. Hachette Books, 1998, pg. 27.

- Bilby, Joseph G. Irish Brigade In The Civil War: The 69th New York And Other Irish Regiments Of The Army Of The Potomac. Hachette Books, 1998, pg. ix.

- O’Dowd, Niall. “The Battle of Gettysburg: The untold story of the Pennsylvania Irish Brigade.” IrishCentral, https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/battle-of-gettysburg-irish-brigade.

- “The Irish Brigade.” History.com, 14 April 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/the-irish-brigade.

- Egan, Timothy. The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

- Jones, Terry. “The Fighting Irish Brigade – Opinion Pages.” The New York Times, 11 Dec 2012, https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/11/the-fighting-irish-brigade.

- Egan, Timothy. “The Immortal Irishman – Books.” Timothy Egan, https://www.timothyeganbooks.com/the-immortal-irishman.

- “Portrait of Thomas Francis Meagher.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/thomas-francis-meagher.

- “Genl. Meagher at the Battle of Fair Oaks Va., June 1st 1862.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/90714946/.

- Craughwell, Thomas J. The Greatest Brigade: How the Irish Brigade Cleared the Way to Victory in the American Civil War, Crestline, 2011, pg. 122.

- “When The Irish Reaped Harvests of Glory – Ireland’s Own.” Ireland’s Own, 2023, https://www.irelandsown.ie/when-the-irish-reaped-harvests-of-glory/.

- O’Dowd, Niall. “The Battle of Gettysburg: The untold story of the Pennsylvania Irish Brigade.” IrishCentral, https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/battle-of-gettysburg-irish-brigade.

- “Irish Brigade monument at Gettysburg, with photos, text and map.” Gettysburg Stone Sentinels, https://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/union-monuments/new-york/new-york-infantry/irish-brigade/.

- “The New York City Draft Riot of 1863.” History.com, 14 April 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/the-irish-brigade.

- “The New York City Draft Riot of 1863.” History.com, 14 April 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/the-irish-brigade.

- “Recruited Straight Off The Boat? On The Trail of Emigrant Soldiers From the Ship Great Western.” Irish in the American Civil War, 1 October 2015, https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2015/10/01/recruited-straight-off-the-boat-on-the-trail-of-emigrant-soldiers-from-the-ship-great-western/.

- Backus, Paige Gibbons. “Amputations and the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 19 October 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/amputations-and-civil-war.

- Backus, Paige Gibbons. “Amputations and the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 19 October 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/amputations-and-civil-war.

- Stewart, Andy M. “Paddy’s Lamentation (By the Hush).” mysongbook.de, Comment by Janet Ryan, 28 Sep 2000, http://mysongbook.de/msb/songs/p/paddysla.html.

- Ross, John. ““The Best Anti-War Song Ever Made”: On the Trail of Paddy’s Lament.” Irish in the American Civil War, 13 November 2020, https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2020/11/13/the-best-anti-war-song-ever-made-on-the-trail-of-paddys-lament/.

Too, it was hard for the Irish immigrant to trust the Republican party, since many of its leaders had themselves been Know Nothings just a few years prior. Unlike many immigrants, the Irish were relatively politically aware from their first arrival. Nice piece.

Tom

Thanks, Tom. You’re right about the distrust many Irish immigrants felt towards Republicans at the time. The Homestead Act of 1862 was one measure the Republican government under Lincoln came up with that helped to secure Irish support. I also learned how many of those who immigrated from Ireland in the early 1700’s (esp. Protestants from Northern Ireland) held a lot of prejudice themselves against those who immigrated later (mid-1800s). We’ve definitely had a love-hate relationship with immigrants through the centuries. Some who came from Ireland, like Thomas Meagher, definitely arrived with a lot of political knowledge and insight.

Good over view of a complex topic. Egan’s book is well worth the read. Did you you come across any specific info regarding Meagher’s death?

Murder, suicide, accidental? Thank you for posting this excellent read.

Thanks. And no, I did not across anything definitive. There are definitely many theories about his death!

Ms McQuade telescoped a book into two highly informative blogs that were highly informative.