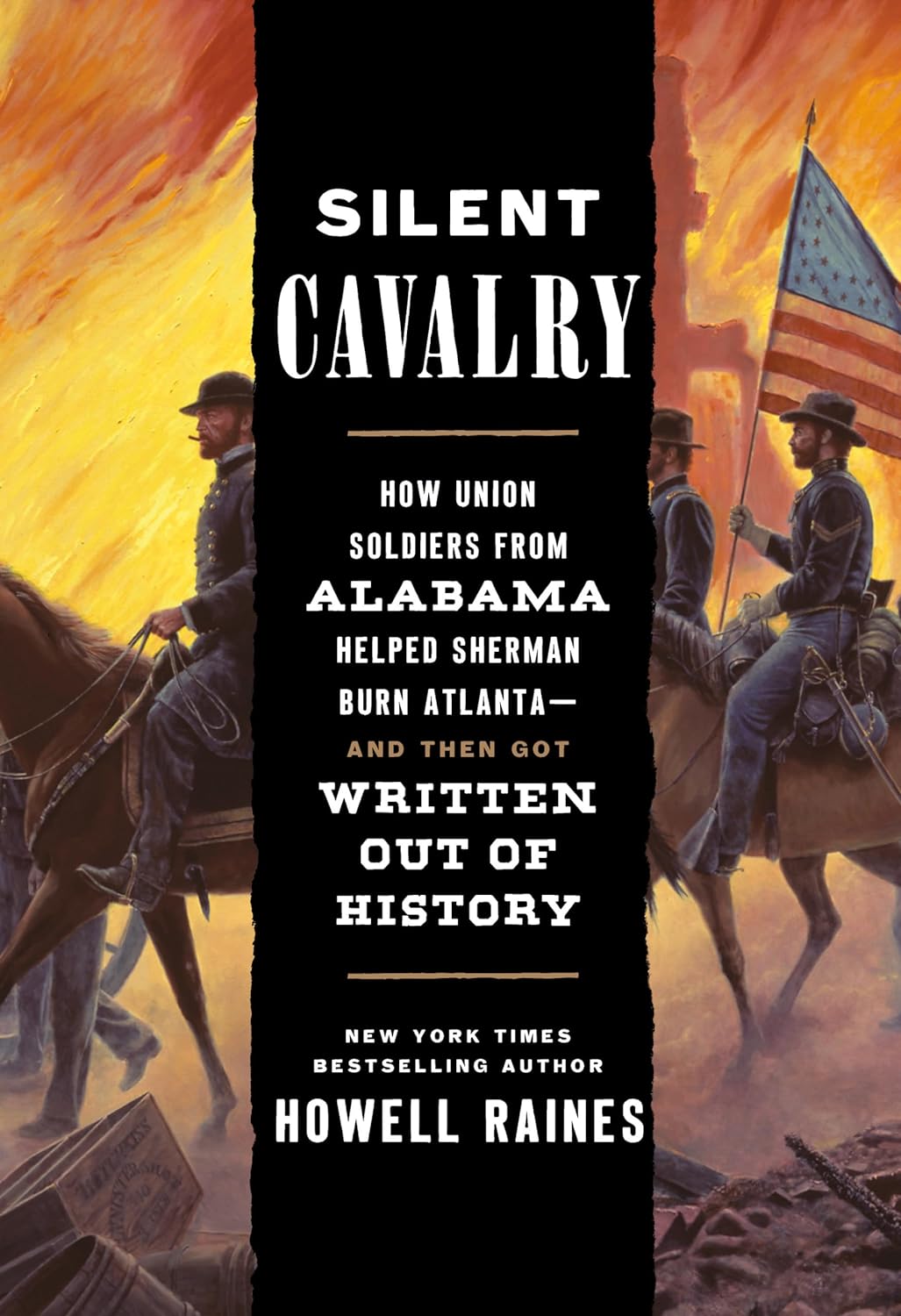

Book Review: Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta and Then Got Written Out of History

Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta and Then Got Written Out of History. By Howell Raines. New York: Crown, 2023. 473 pp., $36.00.

Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta and Then Got Written Out of History. By Howell Raines. New York: Crown, 2023. 473 pp., $36.00.

Reviewed by Doug Crenshaw

Sometimes a book’s title does not neatly fit its full subject matter. Readers of Howell Raines’s Silent Cavalry: How Union Soldiers from Alabama Helped Sherman Burn Atlanta and Then Got Written Out of History might expect it to solely focus on the story of the 1st Alabama Cavalry (US), its role with Gen. William T. Sherman’s army, and why its participation in that action has largely been marginalized in scholarship. And while Raines recounts that story in part, the book encompasses much more. This study also examines the author’s detailed process of searching for the story of that unit, as well as how and why Alabama Unionists at large ended up in the dust bin of history.

Raines spends a significant portion of the book discussing how the hill country people of northern Alabama came to strongly believe in the preservation of the Union. Their portion of the state was not conducive to plantation-type agriculture, and they had little in common politically and economically with their state’s planter-neighbors. To back their sentiments, they raised the 1st Alabama Cavalry, providing most of its 2,066 volunteers (surprisingly, there were also soldiers from New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and 8 men from abroad in the unit). Raines also discusses the severe harassment and persecution the hill country people faced for supporting the Federal government. He paints quite a graphic and moving picture in telling this part of their story.

Raines contends that the role of the 1st Alabama Cavalry in the Civil War was intentionally downplayed by Lost Cause authors in the 20th Century, like William Stanley Hoole, who insinuated that “Alabama’s Unionist regiment played only a marginal role in Civil War combat and that only the oddness of its origins could be of serious interest to historians.” (91) Undeterred by such claims and through dogged research, Raines states that the regiment deserves worthy mention due to its involvement in the Stones River, Vicksburg, and Chickamauga Campaigns. This reviewer could not substantiate that claim but found that the unit did participate with Sherman’s army in the Atlanta Campaign, the March to the Sea, and the 1865 Carolinas Campaign.

The largest portion of the book consists of examining the origins of the Lost Cause, particularly as it related to Alabama. Raines describes how the history of the 1st Alabama and the Unionists of the hill country was buried in the archives, perhaps (even likely) intentionally. Most popular histories of the early to mid-20th Century did not include them in recounting the major campaigns in which they participated, and Raines states that an academic publishing house “had done yeoman’s work in ignoring or defaming Alabama Unionists.” (208) It is quite an interesting and yet disappointing story of the effort of past historians to offer the public incomplete and thus inaccurate histories.

Raines has conducted extensive and even-handed research in both primary and secondary sources. He has examined the first generation of Lost Cause literature, as well as 20th Century historians, who continued the unfortunate tradition of exclusion. He has also studied revisionist works and has uncovered a great deal of new information about Alabama Unionists.

Silent Cavalry is organized roughly into three sections. The first covers the reasons for the lack of information and corresponding misinformation about Alabama Unionists. The second includes the activities of the 1st Alabama. The third offers a long discussion on the rise and endurance of the Lost Cause interpretation in literature and culture.

In several places the text tends to ramble. For example, the book’s discussion of 1950s and 1960s Alabama politics seems somewhat unnecessary, as does the full chapter devoted to Jubal Early. While admittedly Early was a key player in the development of the Lost Cause interpretation of the conflict, a discussion of his 1864 campaign threatening Washington D.C. and his army’s failures in the Shenandoah Valley that same year seems superfluous. There are numerous other such examples, leaving readers wishing for a tighter focus. Unfortunately, the book has few accompanying images, and only two maps, which show the terrain and political leanings of Alabama. The inclusion of maps covering the movements and actions of the 1st Alabama would have been helpful.

Despite the above criticisms, the book also has a number of positives. Raines’s telling of his deep detective work, how he mined unknown information about the people of Alabama’s hill country, and found some records hidden in plain sight, makes for quite interesting reading. Dr. Henry Louis Gates complimented Silent Cavalry by stating that Raines gave “voice to the voiceless.” Kudos to the author for bringing the role of Alabamian Unionists to light and making a significant contribution to the rich and growing historiography on southern Unionism.

If you are looking for a strict regimental history focused around a battle or campaign study, this is probably not the place to search. But, if memory studies and the story of an original research project in the face of decades of adversity and in effort to correct an incomplete historical picture is of interest, this book is certainly worth a look.

Before getting all dewey eyed over the fate of Alabama Unionists, and however much the reader’s sympathies might lie with them, remember that like the Copperheads of the border northwest they were viewed as a potential Fifth column by the majority of the white population in the state. As the reviewer notes this appears less a unit biography documenting an admittedly modest military contribution than another fashionable assault on “Lost Cause” mythology, and its poster boy, the non-Alabamian Jubal Early. It might also be useful to note that these Hill Yankees were hardly subscribers to Garrisons The Liberator. Post War, and in the 1920s, the Klan often found fertile recruiting ground among the rural poor. Their class antagonism toward the plantation elite was not necessarily transferable to solidarity with ex- slaves

1) What’s a “Lost Cause” author or historian?

2) I don’t think the terrain/landscape always had much to do with supporting the Confederacy vs the Union. For example, some of the most enthusiastic Confederate troops came from counties in present West Virginia that had no agriculture to speak of, much less masses of slaves.

Slave owners and members of slave owning families were over represented in the Confederate armies. The regions least involved in the slave labor system were the most loyal to the Union. I don’t doubt the enthusiasm of the west Virginia Confederate soldiers you mention, but of course West Virginia itself seceded from Virginia, remaining loyal to the Union, rejecting the leadership of the Tidewater elite they despised.

A) “Slave owners and members of slave owning families were over represented in the Confederate armies.” Are you certain? Do we have an exact count of Confederate soldiers (including down to all lower enlisted) from slave-owning family versus those who were not? If so, I’d be very curious about the study. If we do not have such counts, such a statement cannot be made.

B) “The regions least involved in the slave labor system were the most loyal to the Union. I don’t doubt the enthusiasm of the west Virginia Confederate soldiers you mention, but of course West Virginia itself seceded from Virginia, remaining loyal to the Union, rejecting the leadership of the Tidewater elite they despised.”

I’m afraid you did not fully read my post. My statement was that at least several current West Virginia counties (out of not very many total WV counties at the time) stayed loyal to Virginia, regardless of how many or how few slaveowners lived there. As I stated, several which did stay loyal to Virginia barely had agriculture (as in they had cattle versus a great deal of tobacco or other crops due to the terrain not being conducive to planting) to begin with, and few slaves. As for “West Virginia itself seceded from Virginia”– it did, over the objection of the populations of some counties. As I said, a number of counties in current West Virginia had populations that were mostly pro-Virginia (i.e. pro-Confederate), as opposed to their leadership (as you mentioned, “elite” leadership) who wanted to secede from Virginia. Elitism existed on both sides. Therefore, you had counties (particularly on the eastern side of WV) whose populations were largely pro-Confederate, while their “leadership” (much of it elite) was pro-Union.

C) The desire of many Western Virginians to join the Confederacy had nothing to do with staying loyal to the “Tidewater elite”. Come to think of it, much of the population of the TIDEWATER area of Virginia itself stayed loyal to Virginia and joined the Confederacy with motives which had nothing to do with staying loyal to “elites”. It would be like saying that I first joined the Marine Corps in the 1990s due to loyalty to the Democratic Clinton Elite. Or that I joined the Army in September 2001 due to loyalty to the Republican Bush elite. It’s a big mistake to assign our own personal opinions to the motives of hundreds of thousands of lower-enlisted folks who lived ages before we were born, and try to guess their personal “loyalties”.

“The regions least involved in the slave labor system were the most loyal to the Union.” True in some cases, not true in others. 2500 Mexican Texans enlisted in the Confederate effort – they all came from West and South Texas where slave ownership was rare. Those counties engaged in stock raising, now known as ranching. Ranching culture was not conducive to slave ownership. Yet, south Texas ranching counties like San Patricio and Refugio, both predominantly Irish, voted for secession in 1861. My own ancestor, son of Irish immigrants who lived in ranching country, served his time in a CSA regiment for a year and then went AWOL. A year later, he raised his own company of cavalry for the CSA war effort. San Patricio county had 77 slaves in the 1860 census. But, 46 of those were owned by one owner. Compare that to just one county, Rapides Parish, Louisiana, which reported 15,000 slaves in 1860.

Bexar County, the county for San Antonio, had 1300 slaves in 1860, but the county was then the size of Rhode Island. Webb County, where Laredo is located, had *no* slaves. Yet, from Webb County came Col. Santos Benavides and his regiment of predominantly Mexican Texans. Benavides’ regiment kept the trading route through Matomoros, Mexico open through the end of the war.

Tom

I wonder how many regimental histories have not seen the light of days – hundreds/thousands? So any “new” book is welcomed. However a Quick Look at Amazon shows several books on Alabama unionist and a multi-volume series on the 1st Alabama Calvary. At $40-$45 a volume I am not that interested in a single regiment. That the Confederacy tried mightily to suppress unionist activities is hardly new. So while the author may of uncovered new information any claim to groundbreaking scholarship seems overblown. If there was a true effort to cover-up the role of the 1st Alabama then I would have thought any evidence would have been destroyed. That the book contains unsupported claims of participation in battles is troubling. Perhaps the 1st Alabama in the grand scope of the civil war is no more or no less important than any other unit. Based on this review I will wait to get it until the Kindle version gets down to $2.99.

It is indeed a good question to ask– if the information is so scarce and heavily guarded, how was the author able to get a hold of it? And you are right– the days of the $40/volume histories are numbered, since likely all of that reference information is now online (on a commercial website or national or state archives) and mostly free now. The only exceptions to those, that I can think of, would be private letters in the hands of family members or private collections, which have not been digitized yet. Indeed, to make a book about things that happened 150+ years ago and about which almost everything is already known and chewed and digested, one has to has to create sensational titles and “thumbnails” and claims to attract attention.

This is an excellent, well-written story about a forgotten part of the Civil War. There must be many more such stories to help us get to the truth of what happened in the war, as opposed to the myths built up by people with agendas.

“Lost Cause literature.” … Is “Lost Cause” like a badge that appears on the cover of said books? How does the author of this review know one Southern oriented history from an evil “Lost Cause” book? Or, are we assuming all histories which evince some fair-handedness for the CSA belongs to the abhorrent “Lost Cause” camp? Military memoirs are military memoirs. They do not generally discuss the politics behind a given war or campaign. Do all military memoirs now belong to the nefarious “Lost Cause” camp?

Tom

I’m coming to the conclusion that “Lost Cause” is the term Northern academics use to describe any book, movie, tv show, academic paper, essay, article, post, video, or statement, which shows Confederate troops in any manner but evil and demonic, or incompetent and foolish, or both at the same time. For that reason, films like Gettysburg or TV shows like North and South could never be made today, because half the screentime portrays Confederate troops favorably. The problem is that because none of the academics in question have ever served in any military or have never studied war and combat in any serious way, they fail to understand the concept that one’s fights, win or lose, are only as valuable and laudable as the abilities and virtues of one’s opponent. If one’s opponent was a ghost, or a blank space, why celebrate one’s victories?

Tom, I think you have an interesting point, especially considering memoirs and postwar recollections. Where is the line actually drawn between a Confederate veteran merely telling a story and pronouncing a political viewpoint linked to or sympathetic with the Lost Cause? The odd part is that many Confederate memoirs do not delve much into politics, but others do at times. I will give one example. Lieutenant John Wilkinson of the CSN wrote ‘Narrative of a Blockade Runner,’ published in 1877. I am using it because I have an anecdote off hand that I know of relevant to this thought. For the most part, it is a standard recollection of Wilkinson’s participation. Where he served, how, who he met, and his opinion on military and naval matters. However, if you look a little deeper, there are other elements. In Wilkinson’s first chapter, he calls Jubal Early the “noblest Trojan of them all,” who will “serve as an exemplar for generations to come” (20). Towards the end of his book, Wilkinson also says Confederates deemed their activity a “holy cause” (248). Again, I would say that 99% of Wilkinson’s book is a standard narrative, but do these comments at the beginning and end make it part of the Lost Cause writings? I would say yes, but someone else might say no. Does that discount the other info in his recollections. I would say no. Just some thoughts to add to the dialogue.

What are “Lost Cause writings”? What is the definition?