Book Review: Black Antietam: African Americans and the Civil War in Sharpsburg

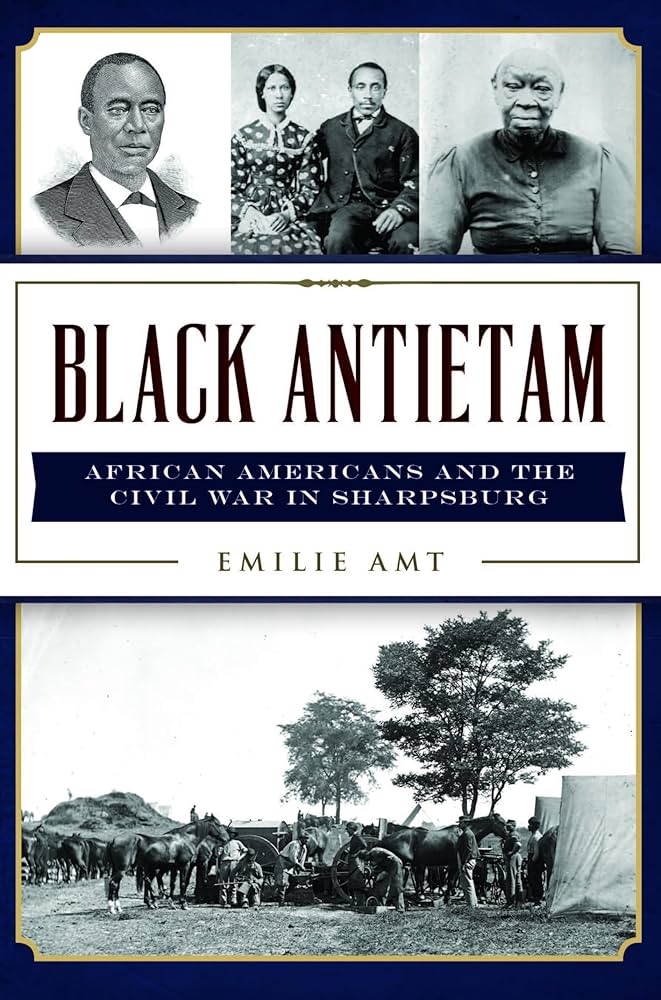

Black Antietam: African Americans and the Civil War in Sharpsburg. By Emilie Amt. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022. Softcover, 160 pp. $21.99.

Black Antietam: African Americans and the Civil War in Sharpsburg. By Emilie Amt. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2022. Softcover, 160 pp. $21.99.

Reviewed by Tim Talbott

Hilary Watson, Hannah and Jared Arter, Susan Keets, Jeremiah Summers, Nancy Camel, and Archie Ridout are not names usually associated with the battle of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign, or even the traditional history of Sharpsburg, Washington County, Maryland or Jefferson County, Virginia (later West Virginia). However, as professor Emilie Amt clearly shows in her book Black Antietam: African Americans and the Civil War in Sharpsburg, people of color were among the rural residents and townsfolk who lived in the area, were within the Union and Confederate armies who clashed there, and experienced the campaign that led to the Civil War’s bloodiest single day.

Black Antietam includes a brief introduction, six chapters, an epilogue, and two appendices. But within its covers, Amt offers more than just coverage of September 17, 1862. Rather, in Chapter 1, to help provide important context, she examines the “Enslaved in Sharpsburg” and the surrounding communities. Amt explains the diverse work roles and often isolated existences of enslaved individuals, who typically lived on small farms. And while the experiences of enslaved people in the Sharpsburg region differed markedly in many respects from those toiling on Deep South plantations growing cotton, rice, and sugar, in some aspects they were eerily similar, too; sales divided families, enslavers enacted violence to coerce labor, and methods of resistance were devised in effort to escape the oppression they endured.

Chapter 2 looks at “Sharpsburg’s Larger Black Community.” This chapter examines free people of color, who made up a number of families in the area. Amt explains that the free and enslaved communities of the region often coalesced, with individuals from each forming relationships with the other for support, protection, worship, and advancement. Also discussed in this chapter is the impact that John Brown’s raid on nearby Harpers Ferry had on the area’s Black population. While the raid in some cases resulted in greater restrictions, it also fostered a hope of freedom someday.

“War Comes to Sharpsburg,” the third chapter, provides readers with a better understanding of the interactions between African Americana and Union soldiers, who occupied the area from early in the war due to their protection of important lines of transportation and communication there. Some Black people sold food to soldiers, thus supplementing their incomes, others fled their enslavers and became officers’ servants or worked for the army for wages. The Confederate invasion of western Maryland in the late summer of 1862 frightened many free people of color, as well those who had fled slavery for the Union army’s protection. Black experiences related to the battle of South Mountain (September 14, 1862) are also included.

Chapter 4, “The Battle of Antietam,” covers the three days leading up to the epic clash, events of the battle, and the day following. Included are several African American accounts giving details of their interactions first with Confederates, and then Federals. During these days, anxiety for the safety of loved ones laboring on isolated farms and working in different situations in Sharpsburg was at a fever pitch. Some fled, but most remained in place to weather the storm of battle in places providing shelter while hoping for the best.

The fifth chapter, “Black Men in the Armies at Antietam,” details the many subservient, but still important roles that African Americans held within the Union and Confederate armies. Whether serving as teamsters, cooks, laundresses, officers’ servants, blacksmiths, or many other vital duties, Black men, and in some cases Black women, provided labor that enabled the armies to fight their battles and the war. Of particular interest is the story of George Slow, a servant for Union officer Frank Donaldson.

“The Crucible of Freedom,” the book’s final chapter, takes a look at the impact that the battle of Antietam had on emancipation. Following the battle, the Army of Northern Virginia’s withdrawal across the Potomac River provided an opportunity for President Abraham Lincoln to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. And although Maryland was officially exempt from the final edict that went into effect on January 1, 1863, it still brought enormous change to the Old Line State, including opportunities for its Black men to enlist in the Union army.

One of the main strengths of Black Antietam is the many first-hand accounts provided by African American eyewitnesses describing these momentous events. Amt offers five of these amazing narratives at length in the book’s first appendix. Another, a “Driving Tour of African American Sites around Sharpsburg,” is also included.

Other works such as Steven Cowie’s amazing When Hell Came to Sharpsburg: The Battle of Antietam and Its Impact on the Civilians Who Called it Home (2022), and Kathleen Ernst’s pioneering Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign (2007), touch on the Sharpsburg area’s Black men, women, and children’s experiences. However, Black Antietam with its primary focus, fills a void in the scholarship. This book will be particularly helpful to students of the Maryland Campaign by providing a more in-depth perspective and creating a greater appreciation for the part African Americans played in the dramatic events leading up to, during, and following September 17, 1862.