Book Review: Lincoln vs Davis: The War of the Presidents

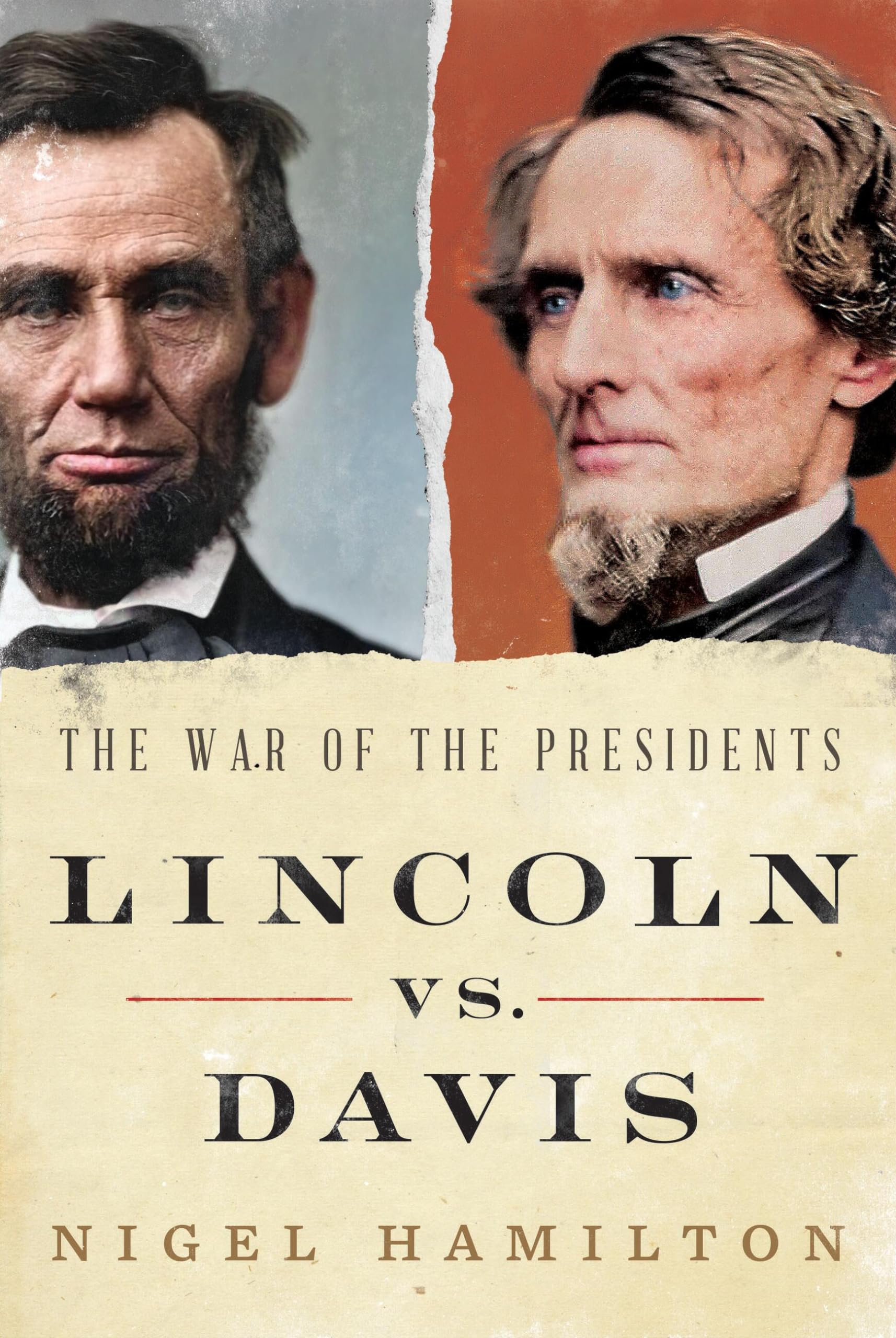

Lincoln vs Davis: The War of the Presidents. By Nigel Hamilton. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2024. Hardcover, 777 pp. $38.00.

By John B. Sinclair

Noted WWII and presidential biographer Nigel Hamilton turns his focus to the American Civil War for the first time with this “dual biography” of Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis during roughly the first two years of their administrations. He begins his story on February 10, 1861, the day that each ironically began journeys from their homes to Washington and Montgomery, Alabama, respectively, for their inaugurations.

Lincoln vs Davis: The War of the Presidents examines each of the leaders’ strengths and weaknesses as Commander-In-Chief. Hamilton uses the date of the Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863, and its immediate aftermath as the ending for the book, believing the outcome of the Civil War at that point became a foregone conclusion. Given the dark days that still lay ahead, some might question this supposition.

The book is a hefty tome. The text is 714 pages plus endnotes, although it lacks a separate bibliography. It consists of ten “Parts” with 91 numbered chapters plus several unnumbered sections. There is little new information and, at least to this reader, no startling revelations. The endnotes sometimes reflect sparse sources, and there are places in the narrative when assertions are made without apparent documentary support in the endnotes.

Lincoln is certainly fair game for criticism for what some see as his slow, evolving views on race and for not making slavery a central issue earlier in the war. Hamilton, however, is unrelenting, contemptuous, and withering in his approach. He even questions Lincoln’s “manhood” on the subject and calls Lincoln “craven.” (338, 364, & 495)

Apparently due to his inexperience with the Civil War, Hamilton overlooks two important events in Lincoln’s learning curve as Commander In Chief. The first is Lincoln’s failure to appoint a commanding general to coordinate a cluster of Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley during Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Campaign, which allowed Jackson to engage them separately and elude their grasp.[1] Although Hamilton briefly mentions the Union capture of Norfolk in 1862 in a 30-word clause as part of a 78-word sentence, (531), Hamilton misses a unique opportunity to examine Lincoln’s growth as a military commander there.[2]

As to Jefferson Davis, Hamilton often criticizes him for missing several opportunities to seek peace during the war and just before the Emancipation Proclamation was officially issued. According to Hamilton, Davis should have announced gradual emancipation in the South. Hamilton provides no details of how this radical change could be effectuated, ignores the political firestorm that would have erupted in the South, and does not consider the likelihood of Davis’ impeachment.

With both Lincoln (whom Hamilton often strangely refers to as “Abraham”) and Davis, the author has an unsettling tendency at times to delve into the supposed mindset of both without convincing documentary support. Some of his remarks seem guided by the benefit of perfect 20/20 hindsight and not by the at-the-time uncertain factors facing both Lincoln and Davis during the war.

Fact-checking could have helped this book. Hamilton claims Virginia holds the distinction of having the highest number of deaths (31,000) among its troops than any other Confederate state. (180) North Carolina would beg to differ. The American Battlefield Trust website lists both states as having equal amounts of deaths at approximately 31,000. The North Carolina total may well be even higher.[3] Hamilton also claims without citation that the battle of Fredericksburg “was the bloodiest battle of the war” up to that point with 17,800 casualties noted (690), which are less than Antietam’s casualties by at least 5,000. He is also apparently unaware of the earlier two-day battle of Shiloh in April 1862, where the total losses exceeded 24,000, including over 13,000 for the Union.[4] It may seem picayune to note such discrepancies, but such simple factual errors raise doubt in readers’ minds about the book’s overall reliability.[5]

There are also problems with interpretation. For example, Hamilton asserts that the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) gave the Army of the Potomac a “thorough drubbing” at Antietam. (641) A rather curious description given the serious damage done to the ANV and Lee’s subsequent retreat from the field and Maryland.

Also troubling are Hamilton’s subtle and not-so-subtle treason allegations against Maj. Robert Anderson, commander of Fort Sumter. Space limitations here prevent a full examination of these claims, but suffice it to say I find those charges wholly unconvincing. Hamilton’s claim that Anderson’s agreement to “evacuate” the fort was premature after “only” 1 ½ days of artillery shelling is shortsighted. Though the exterior walls still held up, the interior of the fort was gutted by fire, food rations were low, only four barrels of gunpowder were left, and the main gates were blasted open, leaving the 75 or so Federals exposed to an amphibious attack. Short of an Alamo fight-to-the-last-man defense, what alternative does Hamilton propose?

Readers may find this book a difficult and exasperating experience. It is excessively long, verbose, has many run-on sentences, contains heavy doses of repetition, too often focuses on minutiae, and offers assorted, obscure references to British history, literature, and Shakespearean plays. In short, the book needed an aggressive and firm editing hand.

In his Author’s Note, Hamilton ponders one day writing a sequel to this book. I hope he chooses wisely.

[1] See, e.g., Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign, Peter Cozzens (UNC Press, 2008) 3-4 & 507-08.

[2] Lincoln Takes Command: The Campaign to Seize Norfolk and the Destruction of the CSS Virginia, Steve Norder (Savas, Beatie, 2020) is one of the best books on Lincoln in recent years to bring new or little known events about Lincoln into sharper focus. Lincoln was on the scene in May 1862 and acted as field commander in the Union naval and army campaign to seize Norfolk and its key naval yard. No one can write an authoritative book on Lincoln as Commander In Chief in the Civil War without consulting this book. Hamilton does not cite it.

[3] “Recent research within the state’s muster rolls and service records, however, has verified 31,954 Confederate deaths, putting a more reasonably estimated figure closer to 34,000.” The Old North State at War: The North Carolina Civil War Atlas, Mark Anderson Moore (N.C. Office of Archives and History 2015) 176.

[4] Shiloh: Conquer or Perish, Timothy B. Smith (Univ. of Kansas Press, 2014) 401 & 421.

[5] Veteran Civil war readers will probably also catch Hamilton’s claim that Cedar Mountain Stonewall Jackson rallied his men by “drawing his sword” and waving it. (607) It is well known that Jackson was unable to draw his sword because it was rusted inside its scabbard. Instead he took the scabbard off his sword belt and waved it with the sword stuck inside in the air. Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain, Robert K. Krick (UNC Press, 1990) 206-07.

John B. Sinclair is a retired charitable foundation president and a retired attorney. He is a member of the Baltimore Civil War Roundtable, a member of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (James A. Garfield Camp No. 1), and a Life Member of the Lincoln Forum.

Thanks for the careful, objective review of this book. I live in a part of Pennsylvania where Southern sympathizers have latched onto two of our local heroes–Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith (a mixed race woman from Gettysburg)–and are continuing the Lost Cause effort to diminish appreciation for the contributions these two made (as a couple) to the betterment of life for all people of color and the nation in general. Thanks again for raising the red flag on this book, and thanks for sparing me the headache I’m sure I would have developed if I tried to read it.

I always learn something from an excellent book review like this one!

The reviewer disagrees with the author’s several condemnations of Lincoln’s cowardice. But the author explains that he believes Lincoln should have been more vigorous in actions to condemn slavery and liberate slaves. The reviewer may not like this aspersion cast on Lincoln, but it is certainly not unwarranted.

I remain convinced that many people – and I’m not including Mr. Kaplan or the book’s author in this – still have little to no idea how the Federal Government functions. They seem to believe that the President is a King and can do things with a wave of his hand, e.g. “Lincoln should have freed the slaves!” Lincoln, despite being President, had no power to free the slaves. Slavery being legal, it could only be ended by Congress passing legislation to outlaw it. To go a step further, slavery was protected by the Constitution; thus, that document would have to be amended in order to end slavery – and it was…nearly four years after the war began, with full ratification and passing into law coming 11 months later…with 11 states being prohibited from participation in the amendment. But in the end, slavery ended in America…where it began…in the North…long after it had ended in the South. But President Lincoln – who said repeatedly that he was fighting the Civil War to bring the Southern states back into the Union with slavery intact – had no real power to end slavery; thus he should not be excoriated for failing to do so, nor credited for doing so.

“According to Hamilton, Davis should have announced gradual emancipation in the South.” The Confederate Constitution expressly protected the institution of slavery. Indeed, the Confederate Congress was expressly forbidden from passing any “law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves.” How does Mr. Hamilton address this rather large legal obstacle to his advice?

Kevin: Excellent point, but Hamilton does not address it. Early in the book, he twice refers to this Confederate constitutional provision. (10-11 & 69) Hamilton does not, however, mention it later when claiming Davis could have issued a counter “emancipation proclamation” of his own in late 1862 to remove slavery as an issue. (588 & 589). Hamilton vaguely alludes to Davis’ wartime powers (367), but he never provides a clear explanation, let alone a compelling legal one, to support Davis’ unilateral authority to end slavery in the South.

The Confederate Constitution, as it was scribed for the duration of the Confederacy’s existence, barred the Confederate national government from passing any laws that affected slavery (at least as long as a Constitutional amendment was never adopted and/or an expression of the war powers of the Confederate Presidency were never held as validly expressed if Davis had unilaterally declared a status upon slavery – as neither of these appear to have ever been attempted, it’s all up to scholarly argument).

There was absolutely nothing to stop the Confederate national government from working in a scheme of cooperation in this regard with the individual Confederate states, who did posses sole and absolute legal authority upon slavery.

This would have been exactly the manner in which the 1862 Confederate Emancipation Treaty between the South, Britain and France would have worked (the Confederate national government possessing sole jurisdiction over foreign affairs), and the later Duncan F. Kenner Mission.

There are many ways to work such a thing. You could, for example, like Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, work with Congress to evoke change in a law or multiple laws in order to bring about something to which both parties agree. You could, for example, like Barack Obama and Joe Biden, issue Executive Orders that illegally violate laws, or the Constitution, or to refuse to obey laws, or brings laws into being, in order to bring about something to which Congress and the People violently disagree and do not want. Also, in times of War or Emergency, Presidents have certain powers they can take without anyone’s permission, though these are understood to be temporary measures to ensure national security, not permanent changes in law or the body politic. Remember, at the beginning of the war, when it seemed Maryland would leave the Union, Lincoln threw Confederate leaders and agitators in prison without Write of Habeas Corpus. People howled, the Supreme Court howled – but it was wartime.

Two men from Kentucky, as was John C. Breckinridge, Vice President to James Buchanan and candidate for President in 1860. Lincoln and Davis moved on to several other states even before they became nationally known, but originated in the great state of Kentucky.

As for the error concerning Fredericksburg/Sharpsburg, it overlooks the Seven Days as well, in which there were 37,000 casualties. Only Gettysburg exceeded the Seven Days for casualties, yet historians consistently overlook this.

Mr. Schafer: Regarding your latest December 26th comment, many of us join this forum to share our interests in the American Civil War – not to engage in polemics about current American politics. Perhaps you could be respectful about other ECW member political views and avoid current politics?

No, I won’t do that. History is past, present and even future, and by recognizing things occurring in the present that are repetitions of the past is how we learn from history. Anyone who cares about history has to be aware of Santayana’s quote on what happens if we forget the past.

As well, stating fact is not polemic; only those who wince at hearing those facts want it labeled as “polemic” – and suppressed. It never fails to bemuse me that people who are constantly offering up polemics want those who disagree with them to not speak. Our most recent election is proof positive that many of the issues that caused the Civil War are still with us. As just one example, with Donald Trump once winning the Electoral vote despite losing the Popular vote – just as Lincoln did in 1860, with an astonishingly low Popular vote percentage of 39% – and then winning both the Popular and Electoral votes, we have people coming out of the woodwork screaming, “We MUST do away with the Electoral College…so that people like Donald Trump can never be President!” it is patently clear that not only does the Swamp still exist in full force, but the inclination of many to silence people by taking away their voice and their vote remains strong in many individuals.

As Picasso once said, “We have learned nothing from the past.”

Mr. Schafer: Your attempt to link your criticism of Presidents Obama and Biden with the Civil War seems a stretch to me. While I respect your right to support President-Elect Trump, there is a time and place for discussing current partisan politics. I look forward to your comments on my next book review (if ECW and its patient book review editor, Tim Talbott, permit me!). In the meantime, my regards and wishes for a Happy New Year.

As I pointed out in another post, the workings and incidents of what has occurred in our Federal Government in the past often repeat themselves, and thus there is much to be learned from them. Spend ten minutes watching TV today and you will encounter statements such as, “America has not been this divided since the Civil War,” “Many of the issues of the Civil War are still going on today,” “See? This recent election shows people should not be allowed to vote,” “We have to get rid of the Electoral College (with “whenever we lose” unsaid but meant), etc. What’s more, a favorite epithet used by one political party to slur the other is “White Supremacist – just like the people who started the Civil War.” Both happen to be inaccurate, but that’s beside the point. And, statues and memorials to the Civil War are being destroyed at an alarming rate. Not just Confederate ones; the BLM raids on America in 2020 saw statues of Abraham Lincoln and U. S. Grant destroyed as well.

A key element of the Left today being CRT, constant claims of “America being inherently racist, and founded to propagate slavery, America was built by slaves, and the Civil War was about slavery and racism” are constantly made. Again, all are completely untrue, but they’re all related to the Civil War, and are out there in numbers great enough to be alarming. Thus my pointing out facts, not opinion, but facts in my post on the review, as to the workings of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches of the Government, and correctly, factually pointing out instances in the present day where things are done just as they were done in Lincoln’s administration, is entirely appropriate and illustrative.

What apparently is amiss here is people being offended by facts that displease them. For that I have no salve, other than my grandmother’s oft-used statement, “The Truth is like balm – it burns when it goes on, but then it soothes.”

While not considering myself as much more than a life long Civil war Buff with a strong interest in history, I feel qualified to say that I support your conclusions about this work. I had the feeling that the author started out with preconceived opinions about the war, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln and tailored his limited supporting references to fit those opinions. For example, Hamilton totally ignores Lincoln’s long established anti-slavery position prior to his election as president. Indeed, Lincoln’s election and the position of “Black Republican’s” on the slavery issue was the main issue that decided the country. Then I took the trouble to read about the author. I found that Mr. Hamilton has written 29 books published over a 51 year period, a tremendous output. I can’t imagine how much time has been devoted to historical research for each work, when the author is cranking out supposedly serious historical works over such a limited time period.

I am a middle school history teach and am more of a “jack of all trades” than an expert on any one topic. I did enjoy this book but at the same time agree with everything the author of this review article stated. There are certainly parts where the reader may skip ahead as it drags on and on, especially the European references as well as Shakespeare.

What I truly wanted to comment on were the small items that raised red flags for an amateur historian like myself. The book mentioned Edmund Ruffin “coming from Ohio.” Being an Ohioan myself and the fact I teach my 8th graders about Ruffin, this surprised me, I have never read that he ever lived in Ohio. Perhaps he travelled here? Yet, I could find no proof anywhere of an Ohio tie to Ruffin.

Another small but rather odd comment was when Hamilton mentioned that “Lincoln wasn’t even in the Oval Office when the Cabinet delivered their message.” Even an amateur such as myself knows that there was no “Oval Office” in 1862; I would assume the author meant Lincoln’s office at the time which is now the Lincoln bedroom.

Anyhow, I did enjoy certain parts of the book. One such area was the relationship between Jefferson Davis and his wife Varina.

Overall I am glad I read this but also glad to have found this review backing up my questions I was beginning to have about all the factual content.