Suffering for Serving: Violent Opposition to Black Enlistment in Kentucky , Part I

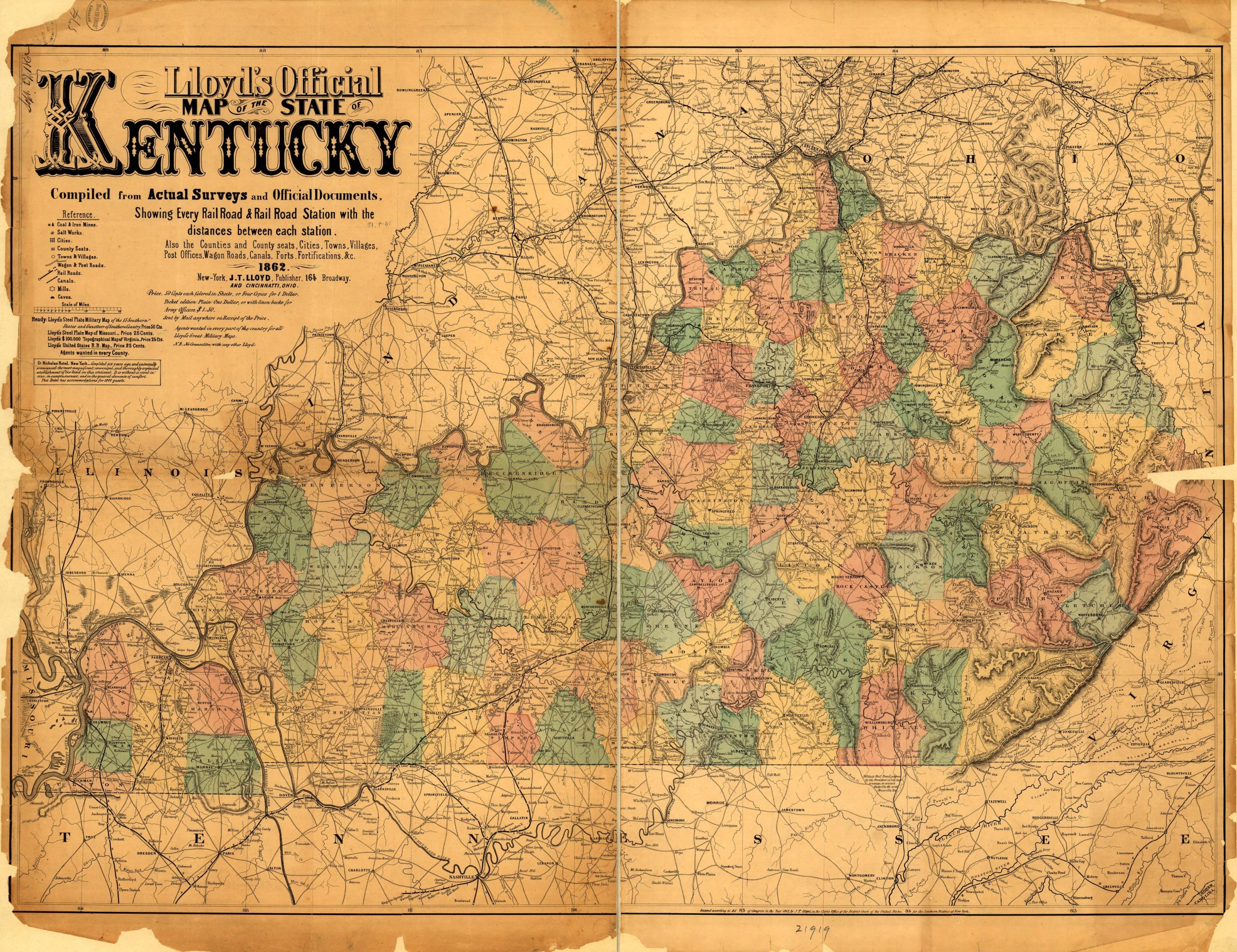

On June 15, 1865, Capt. James M. Fidler, the provost marshal for Kentucky’s Fourth Congressional District, submitted a report that listed several instances of outrages committed against Black men and white officers trying to recruit and enlist United States Colored Troops soldiers in the U.S. Army within his jurisdiction. For those well versed in white Kentuckians’ opposition to African American enlistment, they probably come as no surprise, but for those less familiar, they serve as excellent examples of the lengths that the state’s opponents would go to in attempt to dissuade Black men from joining up.

One might ask, why the opposition? After all, following a brief period of neutrality in 1861, Kentucky’s legislature decided to remain loyal to the United States. Despite their avowed Unionism—one based largely upon a desire to maintain the status quo of established political and social institutions—white Kentuckians viewed Black enlistment as a steep slippery slope toward Black citizenship, and thus equality. Since declaring loyalty to the Stars and Stripes in September 1861, Kentuckians witnessed perceived threats from without to their traditional ways of life. The Second Confiscation Act, the Militia Act of 1862, the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and the final Emancipation Proclamation—of which they were excluded—all dented white Kentuckians’ confidence that things would remain the same in the Bluegrass State concerning their desired relationship with African Americans.

But back to Capt. Fidler’s list. In it he wrote that on May 10, 1864, 17 Black men made their way to Lebanon, Kentucky, expressing their interest to enlist. They received passes to return home and inform their enslavers of their desire to join up. Before they could do so, “a mob of young men of Lebanon followed these black men from town, seized them and whipped them most unmercifully with cow-hides. Further . . . they declared that ‘negro enlistments should not take place in Lebanon.’”

After Fidler arrested the assailants, he explained, “I was threatened with a mob.” The second incident occurred in nearby Adair County. There, a Black man, after attempting to enlist, “was seized by the young men of the place, tied to a tree and subjected to the most unmerciful beating.” In Taylor County, which was located between Lebanon’s Marion County and Adair County, “a colored man, while in route . . . to enlist was seized . . . badly whipped, and consigned to jail as a runaway.” In Nelson County, “Negro men were chased and killed . . . attempting to enlist.” Meanwhile, “In Green Co. violent speeches were made, the Depty. Prov. Mar. threatened, and negroes knocked down when they spoke of enlisting.” Spencer County’s deputy provost marshal “was severely beaten with clubbed guns, and chased from his home for attempting to do his duty.” And finally, in Larue County, “a Special Agent was caught, stripped, tied to a tree and cow-hided for enlisting slaves.”[1]

After receiving instructions on May 13, 1864, from the state’s provost marshal general “to enlist all negroes who may offer themselves regardless of the wishes of the owner,” a flood of white disgust flowed forth. Fidler noted that “McCann, an Irish laborer” cut “off the left ears of two colored boys who were attempting to reach my Hd. Qrs. to enlist.” And “not less than eight negroes were killed in Nelson Co, for leaving their masters with the intention of volunteering.”[2]

The Sanitary Commission’s Thomas Butler reported that “On the 23rd of May, 1864, about two hundred and fifty able-bodied and fine-looking men assembled from Boyle county, Ky., at the office of the Deputy Provost Marshal, all thirsting for freedom. When this body of colored recruits started from Danville to Camp Nelson, some of the citizens and [Centre College] students of that educational and moral center assailed them with stones and the contents of revolvers.”

Things were so bad that even Black recruits not accepted due to failed physical examinations were to still be enlisted. Writing to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Adj. Asst. Gen. C. W. Foster noted on June 7, 1864 that due to “the cruelties practiced in the State of Kentucky by owners of slaves toward recruits rejected by recruiting officers for physical disability,” they were, if possible, to find them positions “in the engineer, quartermaster or commissary departments.”[3]

A couple of days later, an enlistment official for Camp Nelson wrote to the state’s military commander, Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Brundidge, from Nicholasville asking for advice. He wrote, “There is a slave in the county jail here, confined for no civil crime, but because his master feared he would run off. The boy told me he wishes to volunteer as a soldier. Have I right to take him from the county jail and let him come in the army in the state?”[4]

In an effort to keep their enslaved men from enlisting, enslavers in Pulaski County floated a rumor among potential Black enlistees that “all negroes recruits are branded U.S. at Camp Nelson.” The deputy provost marshal there unnecessarily explained, “It discourages enlistments of negroes very much.”[5]

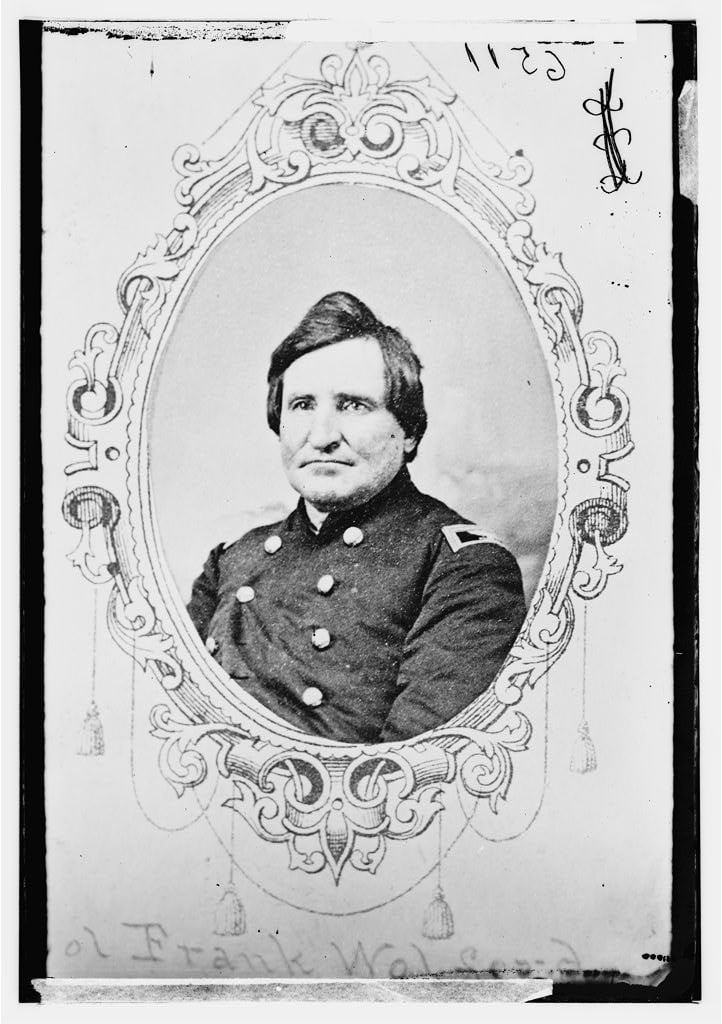

A significant amount of the indignation by white Kentuckians’ over Black enlistments was encouraged by speeches made by men who had served or were currently serving in the United States army. These men’s endorsements of resistance had great effect. Colonel Frank Wolford of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry made several speeches in which he blasted the idea of Black enlistment and President Abraham Lincoln for implementing it.

Wolford was born in Adair County, Kentucky, fought in the Mexican War, and maintained a career as a lawyer and politician in the antebellum years. When the Civil War broke out, he was one of the first Kentuckians to form a regiment to put down the rebellion and preserve the Union. As was the case with the majority of white men, that was all he wanted to result from the war. When the Lincoln administration’s war aims shifted to include emancipation and African American enlistments, Wolford, like many white Kentuckians, wanted their strident opposition to be heard. Unlike others who eventually came to see the value of emancipation and Black in enlistment as helping win the war. Wolford wanted not part of the change.[6]

In a March 10, 1864, speech in Lexington, where he received a jewel-encrusted presentation sword, Col. Wolford was reported by the Maysville Bulletin (reposting a story from the Lexington Observer and Reporter) as saying of Black enlistments: “I[t] was but another of the startling usurpations of power which were being made; and he said it was the duty of the people of Kentucky to resist it as a violation of their guaranteed rights.” The article went on to say that Wolford informed the crowd that “The people of Kentucky did not want to keep step to the ‘music of the Union’ alongside the negro soldiers—it was an insult and degradation for which their free and manly spirits were not prepared. . . .” The newspaper felt Wolford “spoke with all the earnestness, warmth and animation of a man, who felt strong in the consciousness of the truth of what he uttered, and was prepared to stand by what he said regardless of personal consequences.”[7]

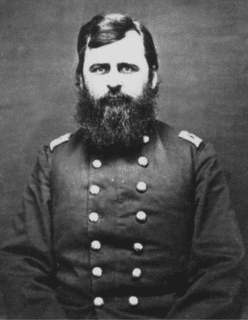

Similarly, Richard Taylor Jacob, former colonel of the 9th Kentucky Cavalry, and at the time lieutenant governor of Kentucky, denounced Lincoln and Black enlistments in speeches. Jacob enslaved 12 people in 1860, and like Wolford was a Mexican War veteran. Jacob was also politically connected, both nationally and in the state. He served with John C. Fremont, his brother-in-law by marriage and the first Republican presidential candidate (1856), in California. Jacob’s marriage to Sarah Benton, daughter of powerful Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, only added to his family connections. He was also related to Zachary Taylor, and his sister married a son of the “Great Compromiser,” Henry Clay.[8]

In early April 1864, in speech at the Paris, Kentucky, Odd Fellows Hall that the 47th Kentucky’s Col. A. A. Clark attended, Clark stated in an affidavit that Lt. Gov. Jacob uttered “seditious language, and strives to provoke and excite the people of Bourbon county to forcibly resist the enlistment of negroes.”

Clark, who took offense at Jacob’s language, started to leave, but stayed long enough to hear the lieutenant governor say, “I know that Lincoln’s tools don’t like to hear the truth; no Kentuckian who is not a slave will ever support him [Lincoln] in his lies or tyranny, but will resist him with arms in his hands.”[9]

Also in attendance with Clark was the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, Matthew Mullins, and its major, Joseph Stivers. Mullins stayed for the whole speech and noted that Lt. Gov. Jacob “advised the people of Kentucky to rise up in mass and resist with all their power the endeavors of ‘Lincoln and his minions’ to enlist negroes in the army of the United States. That the people in their might and power ought to rise up and go and hurl Abraham Lincoln, the despot, from his seat. That Charles the First of England had lost his head for less offence than Mr. Lincoln’s [Emancipation] proclamation, and that he, Mr. Lincoln, might yet also lose his head.”

Major Joseph Stivers stated that Jacob called “Mr. Lincoln a usurper and tyrant, and the armies of the southern confederacy (so called) should never surrender to the abominable authorities of the United States government, for if they did they would be disgraced, and that if they now laid down their arms to the present administration these States would be unworthy of ever being received back again into the Union.”[10]

[1] Ira Belin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller et al, eds. Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War. New York: The New Press, 1992, 390-391.

[2] Ibid, 391-392.

[3] OR. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891, ser. 3, vol. 4, 422.

[4] Richard D. Sears. Camp Nelson, Kentucky: A Civil War History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002, 67.

[5] Ibid, 70

[6] Frank Lane Wolford biography, Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

[7] Maysville Bulletin, March 17, 1864.

[8] Richard T. Jacob biography, Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

[9] Senate Executive Documents for the Second Session of the 38th Congress, 1864-65; Executive Document 16. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1865, 15-17.

[10] Ibid.

It should not come as no surprise that not everyone who supported the suppression of the seceding states was supportive of ending slavery or equality of the blacks.

Glad to see someone else telling this part of Kentucky history. As a member of the 12th USCHA we have been doing this since 2001. Keep up the good work. Waiting for part 2.

Part 2 is posted and available.