Suffering for Serving: Violent Opposition to Black Enlistment in Kentucky , Part II

Black men who wished to enlist were not the only targets of White Kentuckians’ wrath. Black women, particularly soldiers’ wives, suffered at the hands of those who feared potential changes to the states’ social and political institutions, too. Patsey Leach, whose husband enlisted in the 5th United States Colored Cavalry, testified in March 1865 at Camp Nelson that her enslaver, Warren Wiley, “knew of my husband’s enlisting before I did but never said anything to me about it. From that time he treated me more cruelly than ever whipping me frequently without any cause and insulting me on every occasion.”

One day after tending the garden and watching some Black soldiers march past on the road, Ms. Leach returned to the kitchen. There, Wiley “knocked me to the floor senseless, saying as he did so, ‘You have been looking at them darned Nigger Soldiers.’” When Leach recovered her senses, she said Wiley beat her with a cowhide.[1]

After Julius Leach [Leich in his service records] was killed at the battle of Saltville, Patsey received another beating from Wiley. He told her that her “husband had gone into the army to fight against white folks,” and Wiley “would let me know that I was foolish to let my husband go.” He raged that he would “take it out on my back” and “kill me by piecemeal.” Wiley hoped “that the last one of the nigger soldiers would be killed.”

Patsey received two more whippings with Wiley making similar expressions. During the last beating, Patsey testified, “He took me into the Kitchen tied my hands tore all my clothes off until I was entirely naked, bent me down, placed my head between my Knees, then whipped me most unmercifully until my back was lacerated all over, the blood oozing out in several places so that I could not wear my underclothes with their becoming saturated with blood. The marks are still visible on my back.” Patsey Leech fled with her youngest of five children and made her way to Lexington and then Camp Nelson. She wanted to get the rest of her children, but dared “not go near my master knowing he would whip me again.”[2]

George Washington, a Black soldier serving at Taylor Barracks in Louisville, wrote President Abraham Lincoln on December 4, 1864. In his letter the 48-year-old soldier asked for a discharge to take care of his wife and children who labored for “a hard master[,] one that loves the South [and] hangs with it[.] he does not give them a rag [for clothes] nor havnot for too y[e]ars[.] I have [heard][,] all he says [is] let old Abe Giv them Clo[th]es[.]”[3]

On March 24, 1865, Martha Cooley swore in an affidavit at Camp Nelson that her enslaver, John Nave of Garrard County, beat her after she expressed her desire to go to Camp Nelson. Cooley’s husband, like Patsey Leach’s, had been killed at Saltville. “I will give you Camp,” an enraged Nave shouted, and he “immediately took a large hickory stick with which he commenced beating me. He gave me more than thirty blows striking me on my head and shoulders and breaking one of the bones in my left arm.”

She told Nave she wanted her children, and he said “I could neither have my children nor my clothes.” Nave beat her again for asking. Cooley found a chance to runaway to Camp Nelson, but had to leave her children behind, but expressed that she “was very anxious to get my children [back]. . . .”[4]

Frances Johnson, the wife of 116th United States Colored Infantry soldier Nathan Johnson, testified that after Nathan enlisted in May 1864 by going to Camp Nelson, her enslaver, Matthias Outton of Fayette Count, told her that her husband “and all the ‘niggers’ did mighty wrong in joining the Army.” Frances remained with Outton until during a sick spell she received a severe beating in March 1865 by his 32-year-old son Thomas. “While beating me he threw me on the floor and as I was in this prostrate and helpless condition he continued to whip me endeavoring at one time to tie my hands and at another time to make an indecent exposure of my person before those present. I resisted as much as I could. . . .” Frances suffered pain in her head and side from the thrashing. Early the following morning she fled to Camp Nelson.[5]

After her husband Elijah Burdett enlisted in the 12th United States Colored Heavy Artillery, Clarissa Burdett’s Garrard County enslaver, Smith Alford, beat her “over the head with an axe handle, saying as he did so that he beat me for letting Ely Burdett go off.” Clarissa explained that Alford “bruised my head so that I could not lay it against a pillow without the greatest pain.”

After her niece fled to Camp Nelson, Alford asked Clarissa where she went; not answering, he “whipped me over the head and said he would give me two hundred lashes if I did not get the girl back before the next day.” Delaying the follow up beating for a day, Alford tied her hands, “threw the rope over a joist stripped me entirely naked and gave me about three hundred lashes.” Despite Clarissa’s cries for mercy, Alford grabbed her by the throat “and almost chocked me then continued to lash me with switches until my back was all cut up.” Clarissa was given a day to get her niece back. Knowing she would not be able to, she fled to freedom at Camp Nelson, too.[6]

Perhaps the saddest account comes from testimony provided by Pvt. Joseph Miller, a soldier in the 124th United States Colored Infantry. Miller’s and his family’s suffering was particularly unfortunate as it came at the hands of the U.S. Army.

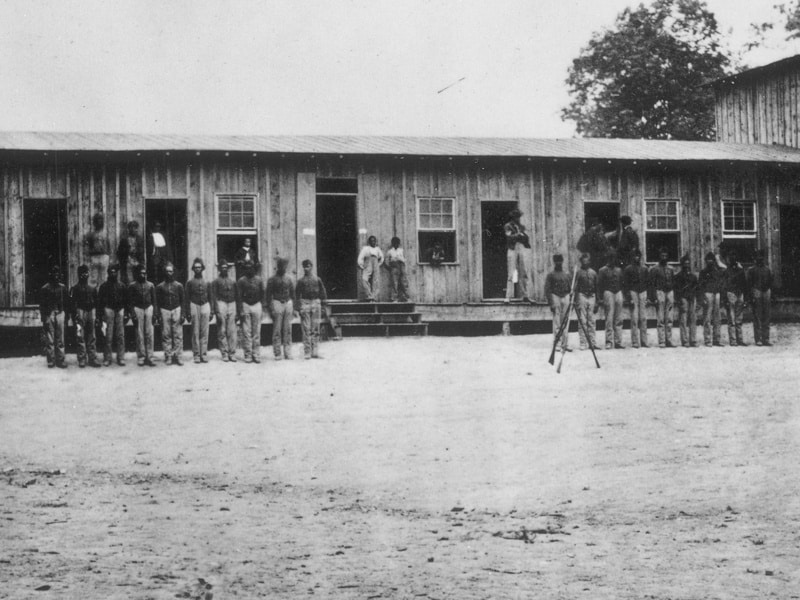

Due to the large number of wives and children that followed recruits to Camp Nelson, more than once the soldiers’ family members received orders to leave the camp. In November 1864, during a particularly bitter cold spell, camp commander Brig. Gen. Speed Fry issued an order for the soldiers’ wives and children to depart from the camp. Captain Theron Hall, Camp Nelson’s quartermaster, reported that “I came to Camp on the evening of the 25th and found that the order had been executed indiscriminately. I found that large numbers were congregated at Nicholasville; some had found their way to Lexington, some were sitting by the road-side and all were suffering from cold and hunger.”

On November 26, 1864, Pvt. Joseph Miller provided heartbreaking testimony about his family’s experience. Miller, from Lincoln County, came to Camp Nelson on October 1864 to enlist. He testified that “my wife and children came with me because my master said that if I enlisted he would not maintain them and I knew they would be abused by him when I left.” Miller’s wife and four children lived with him in a tent within the camp’s limits. At about six o’clock on November 22, without previous warning, Isabella Miller was told to leave camp before morning. Unable to do so due to one son’s illness, they remained until November 25, when they were ordered out again. “The morning was bitter cold. It was freezing hard. I was certain that it would Kill my child to take him out in the cold,” Miller said. The guards, being undeterred, forced the Millers to go.

That evening after duty, Pvt. Miller went searching for his wife and children. He found them in Nicholasville, about six miles from Camp Nelson. They found refuge in a church, but “the building was very cold having only one fire,” and there were too many refugees already huddled around it for his family to get any warmth.

“I found my wife and children shivering with cold and famished with hunger. They had not received a morsel of food during the whole day. My boy was dead. He died directly after getting down from the wagon. I know he was killed by exposure to the inclement weather,” Pvt. Miller explained. Dutifully, Miller walked back to camp to report for roll call. He went back to the church the next day and bur,ied his son, digging the grave himself. An additional record, a sworn statement by A. A. Livermore, who served as the sexton at Camp Nelson shows the sad fate of the Miller family:

“Joseph Miller, Jr. (son of Joseph Miller, Sr.) died December 17, 1864.

Isabella Miller (Wife of Joseph Miller) died December 17, 1864.

Maria Miller (daughter of Joseph Miller) died December 27, 1864.

Calvin Miller (son of Joseph Miller) dies January 2d, 1865.

Joseph Miller, Private, 124th U.S.C.I, died January 6th, 1865.”[7]

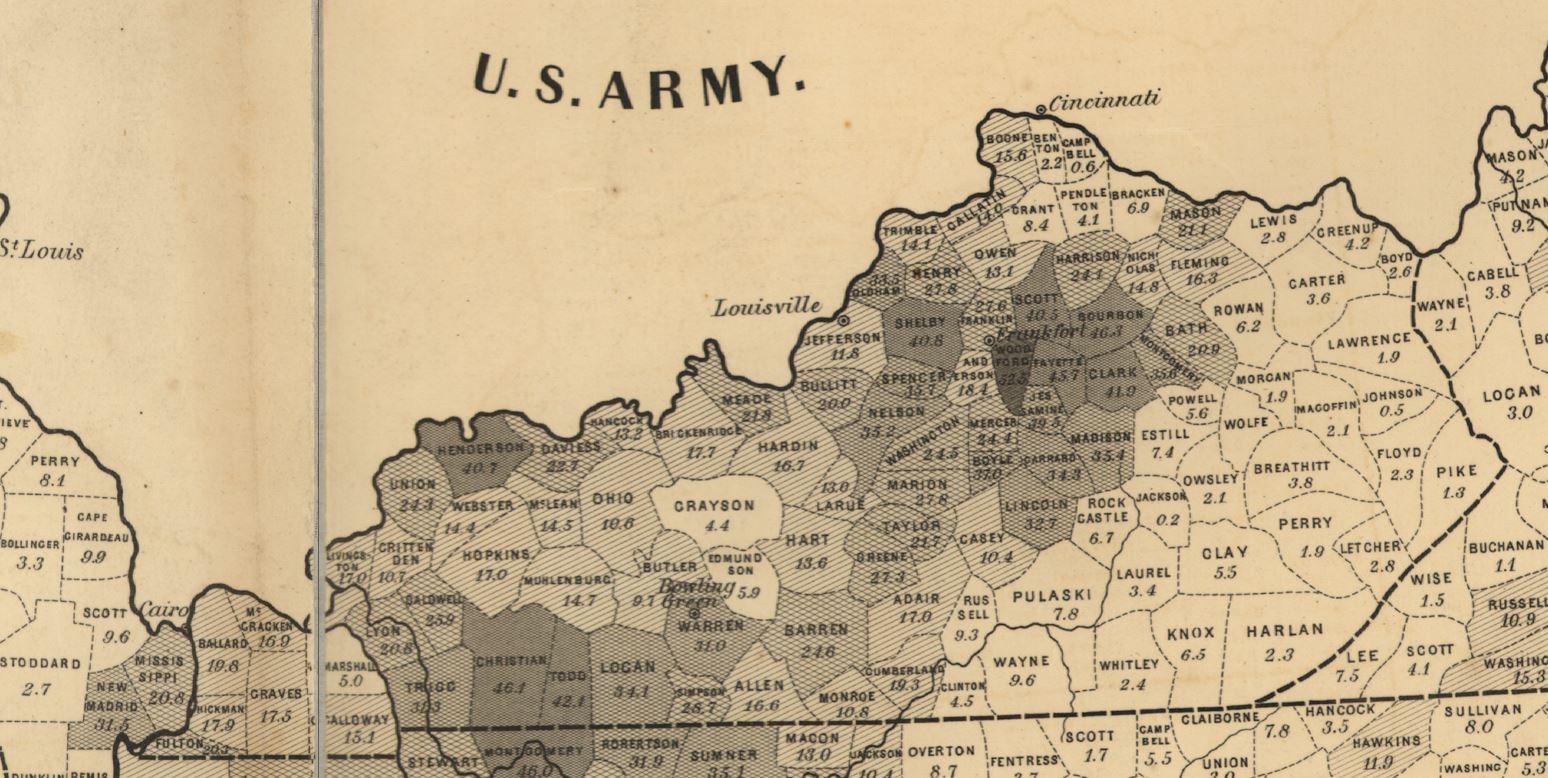

Despite the many efforts to keep them from the ranks, Kentucky eventually sent more Black men into the Union army than any other state, except Louisiana. Officially, Kentucky enlisted 23,703 men, whereas Louisiana receives credit for 24,052 soldiers, a difference of merely 349 enlistees.[8] However, if one were to count the men from Kentucky who ended up enlisting in units raised in Tennessee, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and even Massachusetts, it is beyond doubt that the Bluegrass State would be first. What makes Black Kentuckians’ contributions to the Union war effort even more impressive is that due to the state’s strident white backlash and the Lincoln administration’s fear of potentially pushing the state into the Confederacy, those other states began recruiting their USCT regiments many months before Kentucky did.

[1] Ira Belin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller et al, eds. Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War. New York: The New Press, 1992, 400-401.

[2] Ibid, 401.

[3] Ibid, 495.

[4] Richard D. Sears. Camp Nelson, Kentucky: A Civil War History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002, 186.

[5] Ibid, 188-89.

[6] Ibid, 190-191.

[7] Ibid, 220.

[8] https://afroamcivilwar.org/united-states-colored-troops-history/

Tim, thank you for sharing this tragic but important narrative.

I am so glad that you are making these stories available at a time when they are being erased in our National Battlefields, Monuments and Parks because they make some feel uncomfortable. That is the purpose of history – To make us feel uncomfortable, to make us feel proud, to make us feel curious and ultimately to lead each one of us to make a judgment about who we are and how we became the way we are. Keep up the good and honest work.

Tim, I am grateful you have written this two part series on a part of a troubling and thought provoking history that I did not know.